SALT LAKE CITY — One hundred years ago, immigrants disembarking at Ellis Island were sent home if they had a serious medical condition — or even if they had a hernia, varicose veins or an eye infection.

Today, only "communicable diseases of public health significance," such as tuberculosis, syphilis and Hansen's disease — along with diseases that require quarantine, such as smallpox or yellow fever — are medical barriers to admission to the United States.

Most health-related barriers come after they have arrived.

Although many refugees and immigrants to the U.S. have access to quality health care for the first time in their lives, they face challenges taking advantage of it that go beyond how to pay the bill.

These range from language barriers to transportation to navigating a system that can be confusing even to American healthcare providers. Some come from cultures in which people only see a doctor if they're seriously ill. Others fear that seeking health care, especially for mental-health problems, could result in their deportation or the deportation of someone they love.

To address the challenges involving caring for immigrants and refugees, the American Medical Association recently adopted new policies calling for, among other things, the protection of immigrant health records and the expansion of health insurance to refugees.

But some of the most important work on behalf of refugee and immigrant health is being done far from the AMA headquarters in Chicago.

In the suburbs of Atlanta, for example, in a small city that’s been called “the Ellis Island of the South,” a doctor born in Syria is among a cadre of volunteers providing free health care for immigrants without insurance.

In Boston, a group of women provides healthy lunches for refugees learning English.

Elsewhere, volunteers offer to drive immigrants to health care appointments, help explain the difference between a primary care provider and a specialist, and provide translation in person and over the phone.

The Americans who are helping refugees and immigrants obtain health care are meeting a critical need in a population that often suffers from chronic health conditions but has even bigger problems to worry about, such as finding a job and paying the rent.

"When a refugee walks in the room, they face a wide range of challenges, and health care may not be a priority for them," said Dr. Heval Mohamed Kelli, a Syrian-born physician in Georgia.

The good news is that you can help if you have a few hours to spare each month — and you don’t need a medical degree.

Help one, help all

On any given Sunday, you can find Kelli volunteering at a health clinic in Clarkston, Georgia, a city that has become a magnet for refugees and immigrants because of its embrace of people born in other lands. In Clarkston, nearly one-third of the population is foreign born, and 60 languages are spoken within its borders.

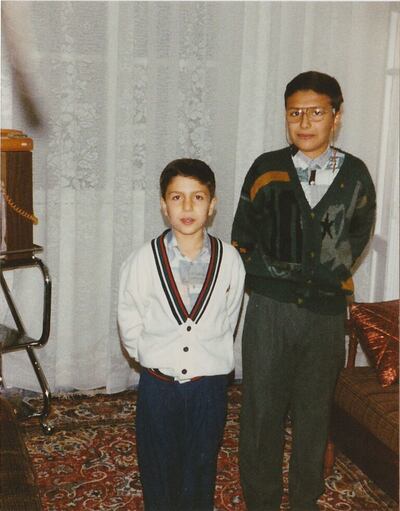

Like the people he serves at the clinic, Kelli and his family were once newcomers here, and they arrived at a particularly difficult time to be a foreigner: two weeks after 9/11.

Kelli, who is 34, was 17 when his family arrived in Clarkston, two years after they'd fled their hometown of Kobane, Syria, where Kelli's father had been severely beaten and jailed for his political views.

Although they were Kurds, a persecuted minority, the family had once lived comfortably in Kobane. Kelli's father was an attorney and earned enough to care for his wife and two sons. After his imprisonment, however, Kelli's father hired a smuggler to get them out, first to Germany, then to America.

When the family arrived in Georgia, only Kelli was able to work; his father was sick and his brother, too young. To support the family, Kelli got a job washing dishes and cleaning bathrooms at a restaurant six miles from their apartment. He would work there while attending Georgia State University and, later, Morehouse School of Medicine. He set a goal to read one page for every dish he washed: If he washed 300 dishes, he'd read 300 pages that weekend.

Although they were poor, the Kelli family had one advantage over many of the immigrants that Kelli sees when he volunteers at the Clarkston Community Health Clinic: In Syria, they'd been able to afford medical and dental care.

“In a lot of countries, people only go to the doctor when they are truly sick," he said. "And most of the refugees I know, the only dental care they get is if their teeth are impacted so bad that they need an extraction. Mammograms, pap smears, colonoscopies — a lot of things that are common sense to us are not common to refugees."

Immigrants and refugees are also sensitive about seeking treatment for mental-health issues. Kelli recalls one patient who refused to accept his diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder. Only after he creatively dubbed the man's condition "bad nightmare syndrome" did the patient agree to get help.

When Kelli and his family arrived, they were bewildered by the strangers who showed up and offered to help them, particularly in the climate of fear that existed in the months after the 2001 terrorist attacks.

But it's because of that help that Kelli and his younger brother were able to succeed in high school and go on to medical school, and he is now passionate about extending help to others, and encouraging others to do the same.

"If every physician would volunteer a few hours of their time in a poor community, it would make a huge difference," he said, adding that helping just one refugee or immigrant is helping the whole country.

'Loathsome or dangerous' diseases

The immigration law that Congress enacted in 1917 was the toughest the nation ever had, as it excluded "all idiots, imbeciles, feeble-minded persons, epileptics, insane persons; persons who have had one or more attacks of insanity at any time previously; persons of constitutional psychopathic inferiority; persons with chronic alcoholism; paupers; professional beggars; vagrants; persons afflicted with tuberculosis in any form or with a loathsome or dangerous contagious disease."

Today, the medical barriers to admission to the United States are more forgiving. AIDS was dropped from the list seven years ago, and doctors no longer hover at immigration entry points, looking to expel people who seem short of breath, which was protocol at the end of the 19th century.

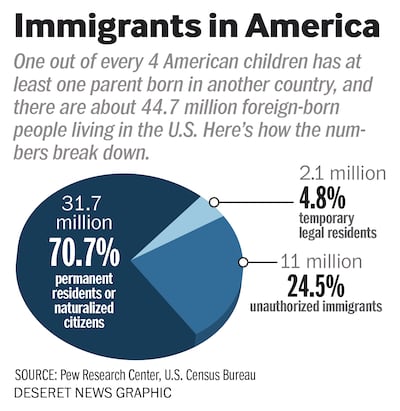

Although some people blame the influx of immigrants to the U.S. when a disease that has been vanquished recurs, the immigrant population is generally healthier than native-born Americans. Immigrants are less likely to get cancer, and they live longer than people born in the United States, according to one study, and they're less likely to smoke.

But refugees, in particular, are more prone to chronic disease, and it's not unusual for them to arrive in the U.S. without ever having had dental care, said Aden Batar, immigration and refugee resettlement director for Catholic Community Services of Utah.

Like immigrants, refugees must have medical screenings before they come to the U.S.; they receive another one within 30 days after they arrive, and receive treatment for any health conditions and immunizations.

Initially, they are on Medicaid, the U.S. health plan for low-income residents, but from the first day, their education in the U.S. stresses self-sufficiency, Batar said. This doesn't just mean financial self-sufficiency but also the ability to take public transportation to get to the doctor or dentist office, and to handle their own paperwork.

Even so, families newly arrived in the U.S. need to be taught the concept of Western medicine: preventive care and screenings, and commonly administered medicines, which are likely unfamiliar. But common American practices are presented while honoring the refugee's culture and tradition: Contraception, for example, would not be an appropriate topic for refugees from Muslim, Orthodox or Catholic backgrounds, which forbid what some health clinics in the U.S. would call family planning, Batar said.

To help refugees and immigrants understand the nuances of health care in America, many resettlement agencies offer seminars that walk newcomers through every aspect, from explaining the difference between a primary care doctor and a specialist to the benefits of preventive care.

Nurses or other people with health care backgrounds would be ideal volunteers to help lead orientations like this, said Diana Jeang, a third-year medical student at Emory University in Atlanta, who established an annual Refugee Health Education Week at Emory.

How you can help

While many refugee and immigrant services are most in need of financial donations, others need volunteers to do everything from teach immigrants how to read and write English and how to fill out medical forms to driving them to doctors' appointments and to pick up prescriptions. Free clinics like the one in Clarkston often need volunteers to help with scheduling and reception.

“If you don’t have medical skills, you have human skills, right?" Kelli said. "You can show up and welcome people, you can teach English, maybe help someone with an application, maybe find someone a better job. It doesn’t have to be something stressful."

One critical need in immigrant health care is interpretation, a service that volunteers can provide either in person or over the phone.

Jeang, the Emory medical student, speaks French but had to learn about non-verbal ways to communicate with people who spoke other languages.

“The alternative is having patients walk out of your clinic, having no idea what happened," she said. "And it’s really common, unfortunately."

Or, if you can cook, you could volunteer to provide healthy food, like the "Ladies Who Bring Lunch" volunteers who provide home-cooked meals through the International Institute of New England, which serves immigrants and refugees in Massachusetts and New Hampshire.

Kelli, who became a U.S. citizen in 2006, said that, ultimately, the most important thing Americans can do is "be present" for refugees and immigrants.

“It’s very important to be present in the community," he said. "I came here 10 days after 9/11. What made us feel welcome in this country was having people show up two days after our arrival. It was very shocking to us; we thought, 'What are these stubborn Christian white people doing in the home of a Muslim family in a poor neighborhood, two weeks after 9/11?' That’s what made me think there is something great about this country.

“If those guys, from one of the most prestigious churches in Atlanta, could come into our home after 9/11, you should be able to go into a community and say ‘welcome to this country.’ Treat them like they’re your neighbors."

But beware one drawback to volunteering that might affect your own health, Kelli said.

“The only thing negative about dealing with refugees is you’re going to gain weight," he said. "They're great cooks; they're very generous. They will feed you and force you to stay for dinner. You will gain weight."