SALT LAKE CITY — On Wednesday night, members of the Salt Lake Astronomical Society drank a toast to a nearly 20-year mission to observe Saturn and its moons.

After completing its final flyby of the moon Titan, NASA's Jet Propulsion Lab announced Wednesday that the Cassini satellite, which has been orbiting Saturn for almost 13 years, was on its final approach in a collision course with the planet.

On Thursday, the tired spacecraft, exhausted of nearly all its rocket fuel, had entered into its final 24 hours of life before it would enter the planet's atmosphere, disintegrate and burn up.

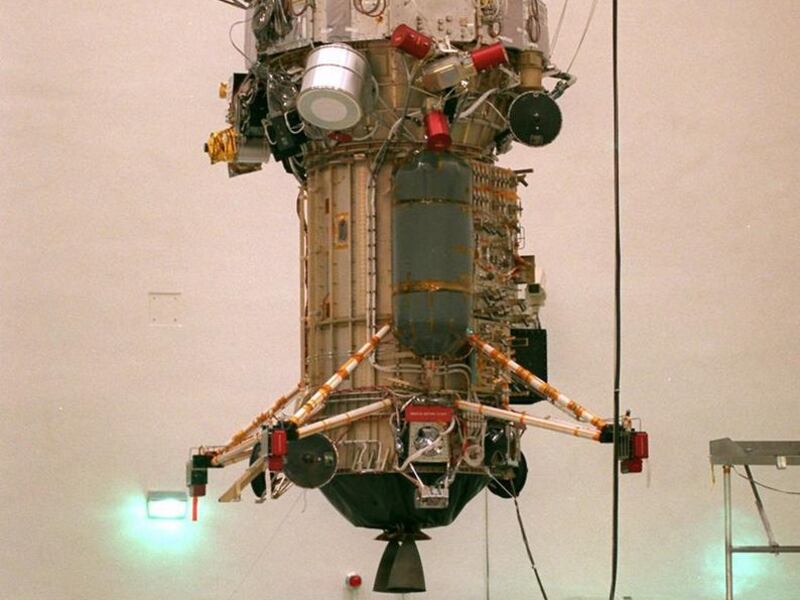

The Cassini-Huygens mission, which launched in October of 1997 and began orbiting Saturn in July of 2004, has been sending information about Saturn and its moons back to Earth for more than 13 years. While the satellite could have continued for some time, Cassini's operators have used up all of its rocket fuel in a seven-year mission extension to perform moon flybys and closely study the Saturn's seasonal changes.

According to a statement by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, the Cassini team chose to crash the satellite in order to avoid a collision with Saturn's moon Enceladus, hoping to avert the risk of microbial contamination to the moon, which scientists have determined could sustain organic life.

In Utah, space enthusiasts and fans of the mission expressed their sympathy Thursday as Cassini approached its final hours.

"They've made so many discoveries, the moons of Saturn, the voids in the rings, they've made a lot of beautiful discoveries and the photography has been fantastic," said Seigfried Jachmann of the Salt Lake Astronomical Society. "I wish it wasn't coming to an end."

Jachmann said he has enjoyed the high-quality pictures transmitted both from the Cassini satellite and the Huygens lander, which was also attached to the mission and which landed on the moon Titan in January of 2005. He noted the lander's approach to Titan's surface as well as the discovery of the moon's lakes of liquid methane and a surface similar to that of Mars.

Patrick Wiggins, the NASA/Jet Propulsion Labs ambassador to Utah, said he is so attached to the Cassini mission that trying to watch its last hours will be "like watching a relative die."

Wiggins said he is going to let the satellite go in peace, choosing not to pay too close attention to Cassini in its last hours and instead wait a few days before reading up on the mission's final reports.

The Cassini team, since April of 2017, has been steering its craft on the Saturn collision course, taking the opportunity in the meantime to perform 22 orbits between the planet and its iconic rings.

"No spacecraft has ever gone through the unique region that we'll attempt to boldly cross 22 times," said Thomas Zurbuchen, NASA associate administrator for the Science Mission Directorate, as the mission's final plans were announced in April. "This is truly discovery in action to the very end."

"We learned more about Saturn in the last decade than in the 450 years since the first telescope was pointed at it," said Seth Jarvis, director of the Clark Planetarium in Salt Lake City. "This has been an astonishingly productive mission that has filled libraries with new information about Saturn and its family of moons."

Jarvis said that it was through the Cassini mission that scientists now speculate that Saturn's moon Enceladus may be able to host life in its salt-water warm ocean, which rests beneath the moon's icy surface.

"That's very exciting and you don't want to risk contaminating it with Cassini accidentally running into it," Jarvis said.

According to the Jet Propulsion Lab's end of mission timeline, the lab was expected to receive a signal about 4:55 a.m. Friday indicating that Cassini is no longer transmitting.

The mission's final hours are being live-streamed on NASAtv and the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory's YouTube channel.