SALT LAKE CITY — As a former contestant on "America’s Top Model," Leah Darrow meets the culture’s prevailing standards for beauty. Her face was once on a billboard in Times Square.

But Darrow, whose disillusionment with the modeling industry began when she heard herself and her fellow models dismissed as “hangers,” now makes a living encouraging women to shed constrictive and demoralizing ideas about how they should look. “The world needs role models, not fashion models,” she says.

A motivational speaker, author and mother of three, Darrow is part of a growing backlash against hoary Madison Avenue notions of how American women should look. Others include Utah sisters Lindsay and Lexie Kite, whose nonprofit organization “Beauty Redefined” seeks to promote positive body image, and CVS, the nation’s largest pharmacy, which announced Jan. 15 that it would no longer use digitally perfected images in marketing CVS products.

Outcry against rigid beauty standards is not new; author Naomi Wolf famously derided the industries that profit from women’s insecurities in her 1990 book “The Beauty Myth.”

Nor are difficult-to-meet standards a product of modernity. As early as 700 A.D., Chinese girls endured tightly bound feet so that their feet would be small. The smaller the foot, the prettier, so the thinking went.

But a quarter-century post-Wolf, even as women comprise nearly half of the workforce and enroll in college in numbers larger than men, most Americans still believe women are valued more for their looks than their intelligence or competence, according to a recent report from Pew Research Center.

Equally disturbing: Only about 1 in 10 American women consider themselves to be very attractive, and nearly one-quarter says they are not very attractive or that they are unattractive.

These findings from the Pew Research Center reveal the struggle many women face as they navigate a world in which their physical beauty — or lack thereof — seems to matter more than their professional achievements or success raising a family. No matter how good they are in every other area of their lives, if women don't believe they're attractive, their well-being suffers, research has shown.

To the rescue come Leah Darrow, the Kite sisters and a growing cadre of voices that say it’s OK — even great — to have a few extra pounds, blemishes, a gap between your teeth, and even some wrinkles.

Also, white American women could learn a thing or two from African-Americans, the Pew report suggests.

Differences between races

In its December 2017 report on gender issues, Pew asked more than 4,500 Americans what they believe society values most in women and men. For women, respondents chose physical attractiveness (35 percent) by a wide margin over intelligence (22 percent), hard work (9 percent) and competence (7 percent).

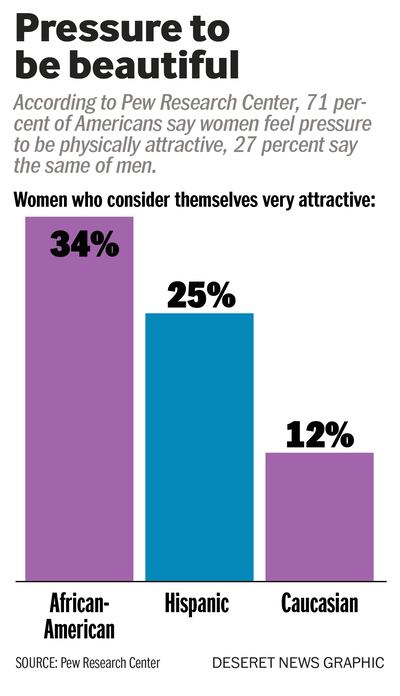

Later, respondents were asked if they believed that they themselves are very attractive, moderately attractive or not very attractive. Just 12 percent of white women said they were very attractive, compared to one-quarter of Hispanic women and 34 percent of African-American women.

White women were also less likely to rate themselves as physically strong than African-American or Hispanic women would rate their strength.

Juliana Horowitz, Pew’s associate director of research, said it’s possible that more people feel better about their looks than they reported. “Even though the survey was conducted online, there are certain things people are less comfortable saying about themselves. Maybe people aren’t as comfortable describing themselves as physically attractive,” she said.

But Pew’s findings line up with past research that has shown that African-Americans have more self-regard than Americans of other ethnicities. Black women are also more likely to consider themselves beautiful regardless of their weight, unlike white women, whose self-image is more likely to be connected to their weight, according to a survey conducted by The Washington Post and Kaiser Family Foundation.

Also, African-American women are less likely than white women to be consumed with thoughts about their physical beauty.

When asked how big a priority being physically attractive is, 16 percent of African-American women in The Washington Post/Kaiser poll said attractiveness is very important, compared to 28 percent of white women.

And according to the American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, white women underwent 75.5 percent of cosmetic procedures in 2016, compared to just 9.7 percent for Hispanic women and 7.3 percent for African-Americans.

Mirna Valerio, an African-American who teaches Spanish and coaches cross-country in Georgia, said that in her family and circle of friends, feelings of low self-esteem related to body size and shape were rare. “Rather, women who were voluptuous/curvy/heavy/thick were seen as beautiful, as were women who were ‘straight-sized.’

“My feeling is that when you are a part of a group that is consistently disenfranchised and outside of societally accepted beauty norms, members of that group develop their own beauty norms to aspire to, whether or not they match the dominant ones,” said Valerio, who writes about being an overweight runner in her 2017 book "A Beautiful Work in Progress."

Julie de Azevedo Hanks, a licensed clinical social worker and psychotherapist in Salt Lake City, agreed that among African-American and Hispanic women, there seems to be more variety in what is considered beautiful.

“You think about J-Lo (Jennifer Lopez), who’s really curvy, or Oprah, and there tends to be more variety in body size and features. There’s a narrower definition of beauty for white women. And we see more white women in general, so there’s more messaging about that.”

The mirror as enemy

According to Pew, Americans also believe men feel pressure to be physically attractive, but not nearly as much as women do. When asked what traits people value most in men, respondents ranked attractiveness in sixth place, behind honesty/morality, professional and financial success, ambition/leadership, strength/toughness and hard work/good work ethic.

The difference between how physical beauty is valued plays out in the marketplace of goods and services that people believe enhances their attractiveness. According to the American Society of Plastic Surgeons, in 2016 women accounted for 91 percent of facelifts, 89 percent of liposuction procedures and 94 percent of Botox and similar injections.

Women also account for about 75 percent of eating disorders.

Part of the problem is that girls are taught from early childhood that they are prized for their looks, said Susan R. Madsen, the Orin R. Woodbury Professor of Leadership and Ethics at Utah Valley University and executive director of the Utah Women and Leadership Project.

“Research has shown that the micro-messaging we give to girls is often different than boys,” Madsen said. “We use words like, ‘Here’s my beautiful daughter.’ It’s so much about looks from the start. We think we’re doing them a favor, being kind. But we’re teaching them it’s about my looks, not my brain.”

One study has found that 82 percent of 10-year-old girls are afraid of being fat, Madsen said. “At 10, they already have this fear. To me, that’s just sad. And social media, on top of TV, is making that out of control.”

The expectations that girls internalize continue long past the insecurities of adolescence, she said.

“I’m surprised by how many women in their late 20s, 30s, 40s and even 50s say they struggle with social media, that they never feel good enough because of this comparison culture that we have,” Madsen said.

In making its announcement, CVS cited research that says 80 percent of women report feeling worse about themselves after seeing an ad for a beauty product. The company, which in December bought Aetna, one of the nation's largest health insurance providers, said in a news release that the decision to only use images that haven't been digitally altered to erase pounds, change skin or eye color and hide blemishes or wrinkles was, in part, for the sake of its customers' well-being.

"As a woman, mother and president of a retail business whose customers predominantly are women, I realize we have a responsibility to think about the messages we send to the customers we reach each day," said Helena Foulkes, president of CVS Pharmacy and executive vice president of CVS Health.

CVS said the change on its own products would begin this year, and the company has asked the manufacturers of beauty products that it carries, such as L'oreal and Revlon, to comply by 2020.

The solutions

Pew’s finding that Americans still believe women are chiefly valued for their looks comes despite years of pushback against unrealistic standards of beauty perpetuated by airbrushed and unhealthily thin models. Such efforts include bans against extremely thin fashion models in some European countries, the fat-acceptance movement, and other body-positive advertising campaigns, such as Dove's Campaign for Real Beauty, launched more than a decade ago.

Lindsay Kite, who with her sister launched the Utah nonprofit Beauty Redefined, said that the body positivity movement has done good, but it errs in keeping the focus on women's bodies and how they look, not what they can do.

“We’re in a rut of continuing to evaluate women on their appearances, even when they look different,” she said.

“Step 2 is to get beyond bodies, to try to look at your body as an instrument for your use, rather than an ornament to be looked at,” Kite said.

Despite its celebrated message, Dove's 2017 report on beauty and self-confidence found that half of girls around the world lack esteem for their bodies, and 8 in 10 are less likely to socialize and participate in clubs or teams if they don't feel good about their looks.

But ironically, participating in a sports team is one of the most effective ways of becoming more positive about one's looks, according to Madsen.

“I’m an advocate of getting girls and young women into sports, and team sports are best for leadership development,” she said. “It’s important to get them to use their bodies, not for people to admire, but to do what bodies are supposed to do: to be strong and work.”

Madsen also said it’s important for parents to watch their language around their daughters, so as to not unwittingly raise them to believe that how they look is what matters most. It’s also important that parents teach their girls to have self-compassion, which, according to one recent report, may matter even more to our well-being than self-confidence.

Darrow, the former model who now advocates for a godly standard of beauty, as opposed to the world’s, agrees that children aren’t getting the right messages early on. She tells audiences about taking her then-2-year-old daughter to the emergency room for an asthma attack and telling her repeatedly, “You are strong, you are brave.” Girls — and women — need to be told that, not that they’re beautiful or pretty, she said.

Hanks said that issues with appearance emerge in girls as young as 8, and “it doesn’t go away with age unless women are consciously doing the work of redefining themselves.” Some women deal with aging with “chronic plastic surgery,” but others are able to care less about their looks as they age.

“Women who are doing their self-actualizing work don’t care as much (about what people think),” she said.

But that doesn’t mean that women who are emotionally healthy stop caring about how they look, Hanks said. They still care about putting their best face forward, so to speak, and exercising and eating right. But that’s about self-respect and self-care, not trying to meet standards established by advertising executives.

Even then, Hanks said, "I don't think many women get to a point where appearance doesn't matter. The goal is that it matters a lot less. That it doesn't define them," Hanks said.

But women can also help each other by focusing on other things, Darrow said.

“If you dare to call yourself as a Christian, we must come to see that we as women are not each other’s competition, but we are sisters in Christ, we are family, and we are called to lift each other up," Darrow said, adding, "The enemy is not beauty, but (beauty is) not everything."