SALT LAKE CITY — The sequencing of social media posts may provide hints that a veteran is in acute distress and at risk for suicide, offering potential to intervene, according to a new study from the National Center for Veterans Studies at the University of Utah.

The findings might hold true for others in distress, too.

"How to Use Social Media Patterns to Identify Veterans at Risk for Suicide" was released as part of the Bob Woodruff Foundation's Stand Smart for Heroes series. The study found veterans who took their own lives were more likely to have recently posted about stressful events, followed closely by posts about emotional distress. The reverse — emotional distress and then stressful events — did not have the same association with suicide, said lead researcher and the center's executive director Craig Bryan, a board-certified clinical psychologist.

He said fewer than 5 percent of veterans who took their lives posted anything obviously suicidal on social media, so finding other clues is crucial.

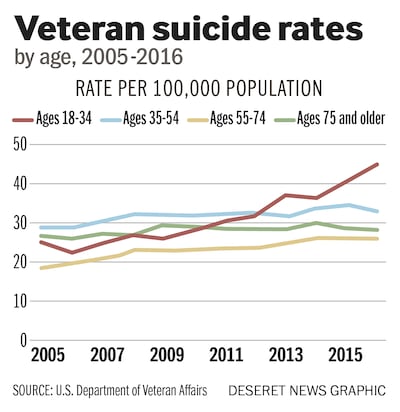

The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs calls suicide by veterans its "top priority." The department's new data finds suicide by young veterans increased 10 percent from 2015 to 2016, even as the rate among older veterans declined slightly. But between 2005 and 2015, veteran suicides had increased 25.9 percent, while non-veteran adult suicides increased more than 20 percent in that time period. Veterans overall are 1.5 times more likely than the general population to kill themselves.

The government agency report notes that about 20 veterans a day die by suicide, accounting for 1 in 7 adult suicide deaths, even though fewer than 1 in 12 Americans have served in the military. Overall, roughly 44,000 Americans take their own lives each year, while there are roughly 25 times that many suicide attempts. Male veterans ages 55-74 had the highest number of suicides, while male veterans 18-34, a much smaller cohort, had the highest suicide rate.

The study of social media posts of veterans who killed themselves showed they were also more likely than others to write about alcohol, to go back and forth quickly between positive and negative emotional content and to post photos of their guns. They were less likely than others to share photos of pets or friends.

Looking back

While the Veterans Administration and others have aggressively targeted suicide prevention, some studies suggest that veterans and military personnel may hide or deny they have thought about suicide.

"Therefore, alternative methods for identifying high-risk service members and veterans need to be developed across all settings providing services to (them), both within and external to the health care system," the Stand Smart report said.

The researchers worked backward, starting with veterans who had died — whether from suicide or other causes — and analyzing social media posts to see if what they said offered insights that might have allowed friends, family and others to reach out to those who took their own lives.

Bryan said the people coding the social media posts for the study didn't typically know how individuals had died.

The study included veterans' posts on Facebook, Twitter, blogs, MySpace and any other social media sites where they interacted. Not surprisingly, Bryan said, some of the traditional markers, like hopelessness, were found.

But not all people who post hopeless or distressed content kill themselves. "So how do you know when a post like this would signal emergent suicide behavior, when at other times it might not?" he asked.

So how do you know when a post like this would signal emergent suicide behavior, when at other times it might not? – Craig Bryan, a board-certified clinical psychologist

They analyzed the posts several ways, including an approach called dynamical systems modeling, which takes into account that people have good days and bad days. But "perhaps it's more informative to look at how content changes over time. Are there certain patterns — cycles in what people are posting online — and are there relationships among multiple variables that can provide information? That is exactly what we found," Bryan said.

No particular theme or topic signaled forthcoming suicidal behavior. But the order and timing of posts did.

"The one that mattered the most was a very interesting sequence: Those who died by suicide tended to post things about life stress, so a relationship failure, conflict with someone else, a financial problem. Then, immediately afterward — perhaps the next post or the one after that — they tended to post something indicating emotional distress or some sort of negative thought process like hopelessness, despair, depression, anger or anxiety."

Taken sequentially, the posts "seemed to be a very strong signal for suicide," Bryan said. But posting in the opposite order was a trait characteristic of the non-suicide group. And the closer the posts were to when the veteran died, the stronger the signal in the sequence was.

Bryan said the "temporal signal seemed highly specific to suicide death."

The most important limitation of the study, he noted, is that it's "historical." Social media is advancing rapidly, with new apps and platforms emerging all the time and how people use different platforms evolves, too. "We are always in some way a little behind the curve."

Some have expressed interest in using rapid technological advancement, such as emerging artificial intelligence, to try to spot people at risk of suicide. But humans beat machines when it comes to watching for signs and reaching out. The researchers said machines don't pick up on sarcasm or irony, while humans do. "We read it, that's obviously a joke. It's lyrics to music or it's ironic," Bryan said.

But the sheer volume of such content has generated some interest in creating algorithms that identify suicidal signals, Bryan said.

How to help

Bryan hopes people won't glue themselves to social media to ferret out who among their friends might be suicidal. But he does want folks to be aware when something seems off. "We often notice when the things people are posting are a departure from their typical patterns," he said. "This notion of being knocked off balance seems to be a really important thing for us to pay attention to. And that might be the time to get involved."

Because so few veterans declare suicidal intent, waiting for explicit posts isn't very helpful.

Instead, when someone talks about emotional distress "in a different way than usual, that's the time to reach out to them."

His advice for reaching out is simple: Same way you would normally reach out to the person. "Some of us text, some call, some of us talk face to face over a cup of coffee," he said. "We don't have to necessarily do anything special or out of the ordinary. It's just kind of being ourselves and reaching out to others when it's obvious they might need support."

Some of us text, some call, some of us talk face to face over a cup of coffee. We don't have to necessarily do anything special or out of the ordinary. It's just kind of being ourselves and reaching out to others when it's obvious they might need support. – Craig Bryan, a board-certified clinical psychologist

Bryan believes paying attention to temporal sequencing of social media posts might find others, not just veterans, at risk of suicide. Other research is confirming that.

A different researcher analyzed Twitter posts of mostly not-veterans, Bryan said, finding "these patterns doubled if not tripled the ability to ID suicidal individuals as well as other conditions. It could improve detection of individuals with psychosis, with depression, with anxiety. (That researcher) took that idea and was able to show it significantly improved risk assessment in a different sample."

The Bob Woodruff Foundation focuses solely on helping post-911 military and their families, says Margaret Harrell, director of programs and partnerships. It was founded after Bob Woodruff, a broadcast journalist who was injured while embedded with American forces in Iraq. He suffered a traumatic brain injury and was comatose for weeks. As he recovered, he and his family launched the organization.

One way they're helping veterans is simplifying and sharing key research affecting veterans, including Bryan's study, which Harrell believes goes well beyond veterans. "There are important things here all of us should know and be thinking about as we're interacting with friends, neighbors, colleagues. … We can apply common sense" and see it applies to others, she added.

"You're talking about literally saving people's lives. It's amazing research," Harrell said.

You're talking about literally saving people's lives. It's amazing research. – Margaret Harrell, director of programs and partnerships

National efforts to prevent veteran suicide include expanding the Veterans Crisis Line, placing a suicide prevention coordinator at each VA facility, increasing access to mental health care and enlisting family, friends, community and others in prevention-focused partnerships, among others, according to the Veterans Health Administration.

Veterans in crisis or anyone worried about a veteran can call the Veterans Crisis Line at 1-800-273-8255 and press 1, send a text to 838255 or chat online.

The crisis line has taken more than 3.5 million calls and dispatched emergency help more than 100,000 times since it started in 2007. More than 413,000 anonymous online chats have occurred since 2009, and the text line, started in late 2011, has responded to nearly 100,000 texts, according to crisis line data.