COTTONWOOD HEIGHTS — After giving birth to her daughter River in April, Kelsey Hixson-Bowles began a quick countdown from 10 — the number of paid days she could take off work.

Hixson-Bowles, 27, scraped together another five days by cashing in the few paid sick and vacation hours she'd managed to accrue since accepting a position at Utah Valley University last February.

When River was a month old, Hixson-Bowles was working full-time from home and a few weeks after that, was back in the office.

"I was just turning that corner, still gaining that confidence as a new mom, and to have to come back and leave her all day," her voice trailed off. "(It) takes weeks to feel that 'OK, I can do all of this.'"

Hixson-Bowles said she is incredibly grateful to her supervisors, who worked with UVU's and the nation's paid leave policies as best they could; she just wishes the policies themselves could have been more accommodating.

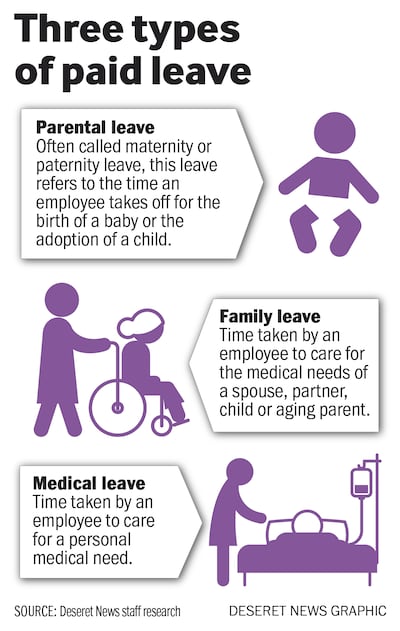

The United States is the only economically advanced country without a national paid family leave policy, instead offering unpaid leave through the Family and Medical Leave Act, or FMLA, which allows "eligible employees of covered employers" to take 12 weeks of unpaid, job-protected leave for birth, adoption or personal health issues.

Instituted in 1993 — 25 years ago this February — FMLA was hailed as a progressive step for employees and families, yet many advocates and legislators say it's not broad enough, and have campaigned for years for a more protective, generous mechanism than unpaid leave.

Although their efforts haven't yet resulted in sweeping national changes, there are a growing number of paid parental leave policies at the state, city, county and individual business level — including a bill now being proposed at the Utah Legislature, HB156, that would provide six weeks of paid, job-protected leave to state employees for the birth or adoption of a child.

Advocates of paid family leave cite studies that show it promotes healthier babies, higher rates of breastfeeding, greater maternal physical and mental health and parental bonding — allowing employees to be caregivers without financial strain.

Critics respond that requiring companies to offer paid leave may financially ruin small businesses, or at the very least, de-incentivize larger companies that already offer generous benefits. Others argue these are family matters the government shouldn't dabble in.

While still debated, the paid leave conversation is generating "a lot of interest and momentum," says Vicki Shabo, vice president of the National Partnership for Women & Families.

"This is an example of a kitchen-table issue that really does impact people's lives quite directly," she said, noting that conversations are happening everywhere.

In addition to state initiatives, Shabo references the 2016 election, in which candidates on both sides mentioned paid family leave; the Trump budget proposal for six weeks of paid family leave; and "Paid family and medical leave: An issue whose time has come," a compromise plan recommending eight weeks paid leave issued by American Enterprise Institute and Brookings, two Washington think tanks on opposite sides of the ideological spectrum.

Paid leave is quickly becoming a "when," not an "if" issue, says Utah Rep. Elizabeth Weight, D-West Valley City, and sponsor of HB156.

She points to Salt Lake City, which started the paid leave trend in December 2016, followed several months later by Salt Lake County. And the LDS Church made national headlines last summer by announcing six weeks of paid maternity leave and one week of paid parental bonding.

"When (employees) can take this kind of leave, not only are they healthier and their children and their families healthier, but there’s a lot more trust in their employer and they come back," she says. "That security and stability for their families … turns into stability in the workplace and for the employer."

But even more than financial support, Weight believes her bill could send a message that Utah supports its employees and families in solid, financial ways — beyond lip service.

"I really like the idea of being able to say … we have a culture of supporting families," says Weight, "(and that the) money invested in employee paid leave actually helps us portray the culture that we say we have."

Existing benefits

Hixson-Bowles still remembers the call from UVU offering her the job of writing center coordinator. She calmly wrote down the information, thanked them and asked for a day to think about it.

After hanging up, she immediately called her college adviser for negotiation advice. She wasn't worried about vacation days or a higher salary. At nearly five months pregnant, maternity leave was the major factor.

In 1993, when then-President Bill Clinton signed the Family Medical Leave Act into law, it assured workers that they wouldn't lose their job or health insurance if they needed to take time off to care for a new baby or adopted child, a sick family member or a personal health crisis.

Yet FMLA is only available to employees who've worked 1,250 hours in the last year for a qualified employer with more than 50 employees; so part-time, new or small-business employees are unprotected. This meant that Hixson-Bowles, as a new employee, didn't qualify to take time off for her baby.

Her colleagues tried offering her some of their paid time off, she said. But sharing PTO is for catastrophic situations only, and although having a baby rocked her world, it didn't count.

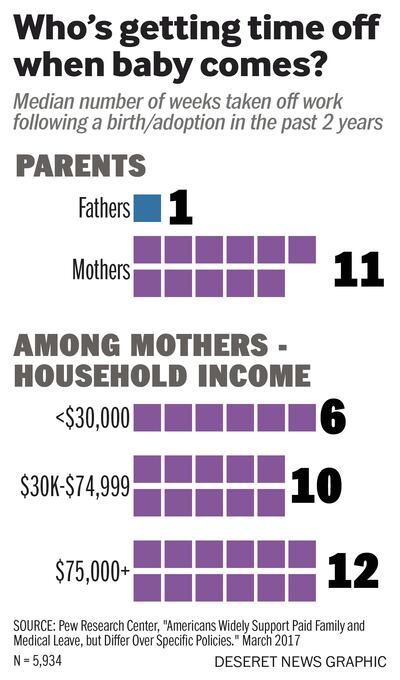

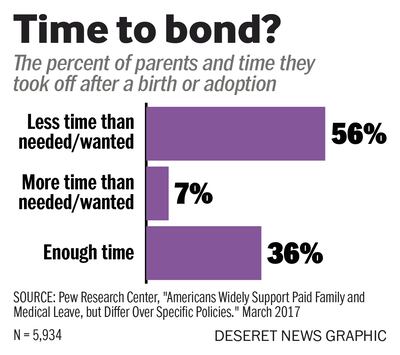

Across the country, 47 percent of Americans took less time off than they needed or wanted for a family or health emergency because they worried they would lose their job, according to a 2017 in-depth report on paid family and medical leave from Pew Research Center.

Another 69 percent said they took less time because they simply couldn't afford it.

Access to paid leave is disproportionately out of reach for those with lower incomes. Among leave takers making less than $30,000, 62 percent had no pay when they took time off for an FMLA reason, compared to only 26 percent of those making $75,000 or more.

In Utah, 64 percent of employees said they can't use FMLA either because they don't qualify or they can't afford it, according to a new report from the National Partnership for Women & Families. Still others find themselves physically unable to return to work any sooner than 12 weeks, and take the whole time off, struggling financially all the way.

Sharalyn Howcroft, an archivist with the Joseph Smith Papers and employee of the LDS Church, had carefully saved up years worth of paid sick and vacation time, but when her twin girls were born in the spring of 2013, it only equalled six paid weeks of leave.

Physically unable to go back that soon and scrambling to finish her online master's degree before her FMLA time ran out, she stayed home for another six weeks without a paycheck.

As the primary breadwinner in their family (her husband, Matthew, is a former telecommunication field engineer who traveled nine months out of the year until they decided he'd become a stay-at-home dad), Howcroft described their situation as "incredibly challenging."

Their flexible spending account had run dry and she found herself waking up at night, wondering how they were going to pay the bills, which, because they had twins, were always doubled.

"The very thing we say as a society that we value most, that people be good parents to children, good children to their parents, right now carries a heavy price tag," said Ellen Bravo, co-director of Family Values @ Work, a network of state coalitions working for policies like paid leave. "A lot of families take a big financial hit for doing exactly what we ask them to do and praise them for doing."

When the LDS Church announced its paid leave policy in June — six weeks of paid maternity leave, plus a week of parental bonding for men and women — Howcroft and her husband were thrilled — she was just months away from delivering their second set of twins.

This time, her entire 12 weeks of FMLA was paid — seven weeks through the new policy and the remaining weeks through her accrued sick and vacation days.

"There just wasn't the stress this time," she says. "We just didn't have the stress of wondering how are we going to pay for this, or questioning, 'Should I be going back to work earlier than I'm going?' just because of the pressure of making money. We were able to spend our time and energy and focus on our babies."

Howcroft is grateful for the policy change and what it says about the LDS Church's support for families, as well as its contribution to the national conversation about paid leave.

"The more policies take care of families," she says, "(that's) doing things to benefit society, because the society starts with families."

Why not?

Yet the United States remains one of two industrialized nations without some nationwide form of paid family leave for new parents, according to the International Labor Organization — Papua New Guinea being our cohort.

By comparison, Chile offers 30 weeks fully paid, Latvia offers just over 53 weeks paid, and Estonia tops the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development chart at 85 weeks of full salary for maternity leave and paid home care to nurture young children. Even Congo and Ethiopia in sub-Saharan Africa offer new moms nine weeks of paid leave.

[Bravo](http://familyvaluesatwork.org/about-us), who's been advocating for paid leave for decades, says that the U.S. doesn't have paid leave for a blend of historical, philosophical and financial reasons.

In the wake of World War II, European countries needed women to work and have babies, so they created policies that supported both, says Bravo. As a result, the average amount of paid maternity leave in the European Union is 21.8 weeks.

Europeans also tend to believe that government has a positive role to play in their lives, so benefits are more generous while taxes are higher, explains Isabel V. Sawhill, senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and co-director of the AEI/Brookings initiative.

In the United States, there's a greater desire to keep the government's power limited and encourage individual responsibility and lower taxes.

Corporate lobbies also wield significant power in U.S. politics, says Bravo, rejecting any policy that might stretch or strain business owners.

Some people simply don't want the government meddling in family issues, says Sawhill, adding that there's chatter about asking Congress to pass a law prohibiting states/cities from passing their own paid leave laws, so national businesses don't have to deal with a patchwork of policies.

Gayle Ruzicka with the Utah Eagle Forum, a conservative advocacy group, believes it's not an appropriate use of taxpayer dollars to "pay for people to stay home." Private companies may do what they want, but bills like HB156 are not a good idea, she said.

Even without a tax hike to fund the bill, the money has to come from somewhere, and if those employees' jobs can be absorbed by their colleagues for six weeks, then why are those employees there in the first place, she questions.

When a baby is imminent, employees should save their money, plus sick and vacation days and use those for paid time off, Ruzicka said. Moms need the time off to recover physically, she said, but paternity leave is "unbelievable" to her.

"The husband does not need that time off to stay with his wife and the baby," Ruzicka said. "I don't even know where that came from. When he comes home from work, (he can) let his wife take a nap and (he can) take care of the baby. Taxpayers do not need to pay for a dad to stay home."

For both parents

Much of the support for paid parental leave, however, extends to the ability of both parents to take it.

A Pew survey from March 2017 found that 82 percent of Americans support paid maternity leave and 69 percent of Americans support paid paternity leave.

Not only does paternity leave help with gender equity in the home, but research also shows that dads who take leave are more likely to be involved with caretaking activities when their child is 9 months old.

During the AEI/Brookings year-long workgroup, there was nothing the entire group agreed on — except the fact that any parental leave policy should apply to both moms and dads equally, said Sawhill.

"Talking about (just) maternity leave is really out of sync with where we are as a culture," she said. "Adding paternity leave as an afterthought — we did not like that."

Salt Lake City was the first city in Utah to offer parental leave for new parents — six weeks of full pay — and due to their predominantly male police and firefighting forces, two-thirds of their 94 leave takers this year were dads, said Salt Lake City human resources director Julio Garcia.

One employee stopped Garcia in the hallway to say that the policy doesn't just boost the morale of the person taking it, but it builds camaraderie among the employees who help fill in the gaps, he said.

"When they know that they have a role in helping a co-worker spend valuable bonding time with their newborn, it creates a sort of 'we are in this together' type of team atmosphere," said Garcia. "We're thrilled to hear that."

The AEI/Brookings workgroup also recognized that their recommendation for eight weeks of paid parental leave is a narrow solution because it leaves out everyone else who uses FMLA to care for a sick child or spouse, help an aging parent or deal with a personal health emergency, said Aparna Mathur, a resident scholar in economic policy studies at AEI and co-director of the report.

"Everyone needs to feel that this is a system they can benefit from," she said, which is why broader family leave is the subject of their discussions this year.

New legislation

Should it pass, Weight's bill would apply to around 18,000 state employees and 37,862 employees at the eight public colleges and universities plus all the University of Utah hospital staff. However, only 1,256 state employees took FMLA leave for childbirth or adoption last year.

Weight wants to decrease the anxiety new parents feel and support them in a critical time in their lives, and she believes her bill can do it without increasing the burden on the state.

Her bill's fiscal note is zero, because employee salaries are already fixed expenses. There is a one-time, $8,000 fee to update payroll systems and a note about "forgone output," or the cost of work that doesn't get done when someone is on leave.

Considering the 1,256 employees who took leave last year, and calculating $10,000 per employee for six weeks, the state could potentially lose $12.6 million if the bill passes. However, under FMLA, employees can take up to 12 weeks of unpaid leave, which means that there's always some level of "forgone output" regardless of HB156's future.

The bill also doesn't address potential costs of hiring a temp or paying other workers overtime when a colleague is out on leave.

When a Salt Lake City employee takes leave, the department can either spread their work among colleagues or hire a temp, using some of the $175,000 set aside for the policy, said Garcia.

Over at Salt Lake County, departments absorb the work when someone goes on leave, says Erin Litvack, Salt Lake County's deputy mayor and chief administrative officer, and whose office is currently down a staffer who's out on paid maternity leave.

"Everybody notices when we're picking up extra workload," Litvack says, "But we really have a culture here at Salt Lake County where people are supportive of each other. … People want to step in and help out."

The county's policy provides for six weeks of fully paid leave for dads and 12 weeks of fully paid leave for moms. Since the policy began in August, 77 employees have taken leave, 47 dads and 38 moms.

Considering a parental leave policy for state employees through HB156 is an important conversation, says Derek Monson, executive director of Utah's Sutherland Institute, but he wants to make sure the discussion isn't rushed.

He's also doesn't want unintended discrimination against families.

If an employer is choosing between two similar employees — one single and one married and of child-bearing age — the employer might hire the person less likely to take parental leave in the near future, Monson says.

He is also concerned about that cost of lost productivity, which would be higher if employees could take paid, and thus longer, leave.

"We should do this the right way that benefits families in a way that's workable for businesses and cost-effective for taxpayers," he said.

Utah Senate Majority Leader Ralph Okerlund, R-Monroe, said he also believes it's a "good time to have a discussion" about paid leave, but was still concerned about potential taxpayer costs.

However, perhaps the fact that the LDS Church — "a major employer in the state" — already offers paid parental leave will help move discussions along at the Legislature, said Senate Minority Leader Gene Davis, D-Salt Lake City.

"The more we see employers instigating this in the private sector," he said, "it only means that the public sector needs to do the same thing."

Looking forward

It's a snowy Friday night in January, and Hixson-Bowles's husband, Jacob Gray, is encouraging River Hixson-Gray to finish her dinner of baby food chicken and rice. She coos and laughs between bites but ends up playing in the food, so he gives up.

River, almost 9 months old, is more interested in crawling around her bedroom, exploring the crib slats, playing with puzzles and swatting at the books Hixson-Bowles is trying to read to her.

She scoots over to dad and squeals as Gray tosses her in the air. "I missed you today," he says, catching her and nuzzling her neck.

While it's still a bit early to talk about siblings for River, when that day comes, Hixson-Bowles will qualify for FMLA, so she could at least take unpaid, job-protected time off. And if Weight's bill were to pass, as a state employee, Hixson-Bowles would be eligible for six of those weeks to be paid.

Though it would be great for Hixson-Bowles, it wouldn't do as much for Gray, who said he'd love to see more cultural support for dads during those first few weeks and months of a new baby's life. He said he often felt "split," trying to provide financially while still offering support physically and emotionally.

Gray's company was understanding, and after giving him a week off, allowed him to work from home. While good in theory, it failed in practice, and Gray ended up back in the office sooner than either of them wanted.

The recent holiday break was great, because it meant time together all day, every day for nearly two weeks.

In fact, River even went with Hixson-Bowles to her office at UVU, playing on a blanket while mom finished a few things.

The duo reveled in the closeness, and Hixson-Bowles noted that it was the longest amount of uninterrupted time they'd spent together since maternity leave. Now, post-holidays, it's back to their regular schedules.

"That's why I've been missing her so much this week," Hixson-Bowles says smiling, her voice slightly wistful. "I got a peek at what maternity leave could have turned into."

.......