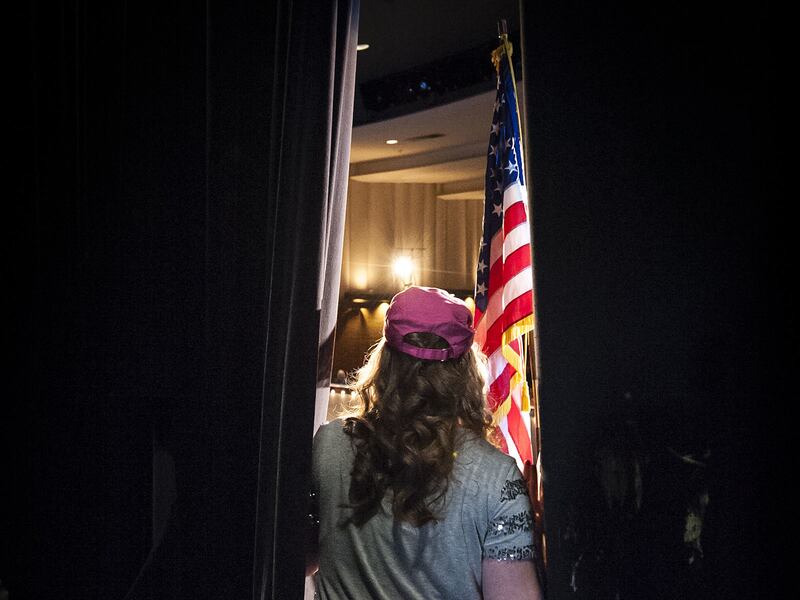

DRAPER — As she prepares for Tuesday's high school graduation, Emily Arthur is a jumble of emotions.

She's headed to college in the fall and looking forward to typical freshman-in-college experiences: dorm living, meeting new friends, going to football games and taking new and challenging classes.

But like most high school seniors, she's also apprehensive about leaving home and the school community that's been her safety net for the past four years.

"I'm happy and I'm excited but a little bit sad. I don't want to let my parents go," she said.

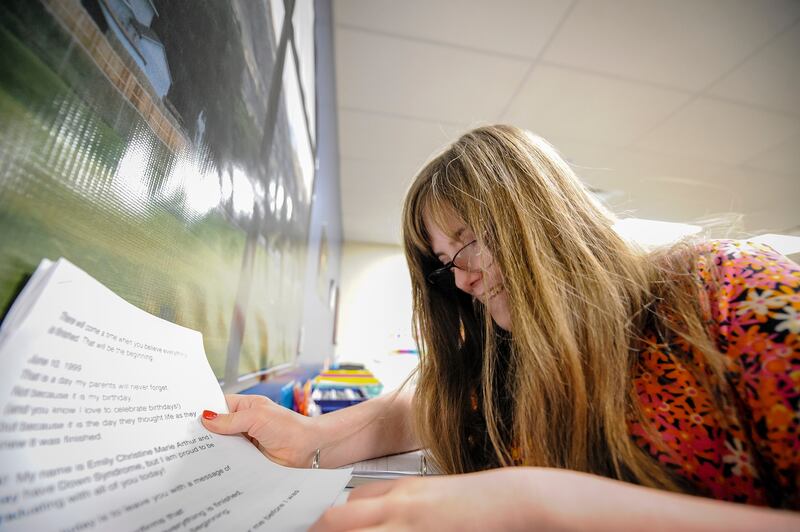

There is much to do before she arrives on the campus of Utah State University later this year. Emily, who has Down syndrome, was one of three seniors selected to speak at Corner Canyon High School's graduation.

She has to memorize her speech so she spends a lot of time rehearsing with mom, her teachers and fellow students.

It's hard, but Emily isn't one to shy away from a challenge.

Her mother, Julie Arthur, wouldn't have it any other way. She has advocated for Emily since she was born, often pushing back against "experts" who have had low expectations for her daughter.

Like the pediatrician who diagnosed her Down syndrome. He stood in the doorway of Arthur's hospital room, remarked on the baby's head of thick black hair and blurted out, "We think she has Down syndrome."

Growing up, Arthur was familiar with just one boy with Down syndrome. Their families belonged to the same country club and she occasionally saw him at the swimming pool "but I didn't know him."

So she asked the doctor, "What should I expect? How bad is it going to be?"

He said, "Honestly, she may never walk. She'll probably never talk. She might not ever potty train."

None of his predictions was right.

This past year, Emily was an honorary cheerleader at Corner Canyon. For football season alone, the cheer squad performed more than 60 cheers and Emily learned 40 of them, her mother said.

She learned to read by the end of first grade. She has been in a mix of mainstream classrooms and special education classrooms throughout school in Pennsylvania and Utah, but she has earned enough general education credits that she will graduate with a standard diploma. Presently, her cumulative GPA is about 3.5.

Outside of school she competes in pageants and is active in church.

This fall, Emily will attend USU as part of its Aggies Elevated program for students with disabilities. Students compete for admission through a rigorous application and interview process. This year, Emily was one of eight students accepted among applicants from Utah and out of state.

"We look for students who are willing to try hard things because college is hard. Neurotypical freshman have a hard time. So students we accept have to be willing to try new things and try the hard things," said Sue Reeves, rehabilitation counselor and career success coordinator.

Aggies Elevated is a two-year program that offers students a mix of career exploration and independent living leading to a certificate of Integrated College and Community Studies. The program, which is funded by a federal grant, is one of a handful of college programs for students with disabilities nationwide. One of its unique features is that students live on campus.

The coursework includes foundational classes in reading and writing, career exploration, navigating adulthood, self-determination, internships and general electives offered to all undergraduate students.

For some students, this will be their only college experience. But for others, it lays the groundwork for them to seek associate or bachelor's degrees.

Newly admitted students live in the dorms with Aggies Elevated students who have completed one year of the program.

It's a major adjustment and like most college freshmen, some Aggies Elevated students get homesick. It's a significant period of adjustment for their parents, too, because they have been intensely involved in every aspect of their children's lives since birth.

"They want the best for their child. As a family, they've decided this is the best thing for them. But they have to be willing to do hard things, too, and sometimes that means letting your child go to do these things. There's no guarantee of success so they have to be willing to let them fail in a safe environment and that's what we try to provide," Reeves said.

Emily says she's excited about her future.

"I'm going to be moving to college and get to know my roommate. I think it will be exciting to learn, to study hard and learn new things. And date," she said with a shy smile.

Julie Beane, a special education teacher at Corner Canyon High, has worked with Emily for four years.

She attributes Emily's success to her mother, who has insisted on educational programs to help Emily reach her highest potential. When Emily first went to high school, she was in a less challenging program designed for students with more severe disabilities. Emily came home from school discouraged.

"She said, 'They're treating me like a baby. Mom, I want to earn real grades. I want to get A's,'" Arthur said.

Eventually, Emily was moved to Beane's classroom, where she teaches "accommodate core" subjects to students with moderate disabilities. Beane's students need a little more guidance and assistance than they can receive in traditional classrooms. Emily also has taken mainstream classes in high school.

"I think she enjoys the challenge of being challenged and enjoys trying to meet those expectations," Beane said.

She also has a sense of humor that can lighten the mood of a room. She jokingly refers to the Deseret News photographer who has followed her the past few weeks as her "paparoxi."

Beane said Emily's brought a lot of joy to her classroom "because she's just fun. She's just a happy kid, but she's sensitive, too," she said.

She learned early on that Emily does not respond well to people raising their voices, so Beane has learned how to "be firm but not sound mean."

"She's trained me how to be a better teacher and person," Beane said.

Emily has been practicing her graduation speech in Beane's classroom with peer tutor Madison Sherwood, who is also a senior.

Her speech is based on an essay by Emily Perl Kingsley, titled "Welcome to Holland." The story is told from the point-of-view of a mom who is raising a child with a disability.

Emily loves the story, so much so that she has a framed copy on her bedroom wall, her mother said.

The shorthand version of "Welcome to Holland" is that life takes you different places than you expect or plan for but those new discoveries can be every bit as rewarding, which Emily says is a good life message for anyone.

Kingsley likens the excitement of having a baby to planning "a fabulous vacation trip to Italy."

One departs on the trip of lifetime and "the stewardess comes in and says, 'Welcome to Holland,'" Kingsley writes.

Holland is not a bad place, "it's just a different place. It's slower-paced than Italy, less flashy than Italy. But after you've been there for a while and you catch your breath, you look around and you begin to notice that Holland has windmills and Holland has tulips. Holland even has Rembrandts," the story goes.

Meanwhile, everyone else comes and goes from Italy. Some brag about what a wonderful time they had there.

"And for the rest of your life, you will say, 'Yes, that's where I was supposed to go. That's what I had planned,'" the story continues.

"But, if you spend your life mourning the fact that you didn't get to Italy, you may never be free to enjoy the very special, the very lovely things … about Holland," the story concludes.

Arthur said parents of children with disabilities invariably mourn the loss of their dreams for their children.

Over the years, she's developed different dreams for her daughter. Emily is very interested in early childhood development. Perhaps that will lead to a career working with children, she said.

Whatever the case, parents of children with disabilities should aim high, she said.

"It shouldn't be any different for a kid with intellectual disabilities. We're trying to raise the best human beings we can, whatever that looks like. That's going to look different for Emily than it does my son, Cameron," she said.

As graduation approaches, Arthur occasionally catches herself weeping that Emily's high school years are drawing to a close and she'll soon be off to college.

She's not sad, she said. It's more of a realization that "it's actually happening."

Arthur reflects on a kindly nurse in the maternity ward in York, Pennsylvania, when Emily was born and doctors suspected she had Down syndrome.

The nurse took time to reassure her and pray with her. She gently explained that her baby had some of the physical characteristics typical of the genetic disorder.

“Either way, she’s the biggest gift you’ve ever been given,” the nurse told her.

She was right, Arthur said.

"It’s been an amazing journey. It really has."