It’s part of who I am, my legacy. It was one of the biggest games in Super Bowl history. I played in two Super Bowls. There are lots of people who didn’t play in any. And then to be able to have something as memorable as that. I’ve always been humbled by it. – Kevin Dyson, on The Tackle

With his young son at his side, Kevin Dyson was flipping through TV channels last Sunday when he saw it: A replay of the defining moment of his life — the final play of Super Bowl XXXIV, played on Jan. 30, 2000.

“There’s Daddy right there,” he told his son.

“That’s you?”

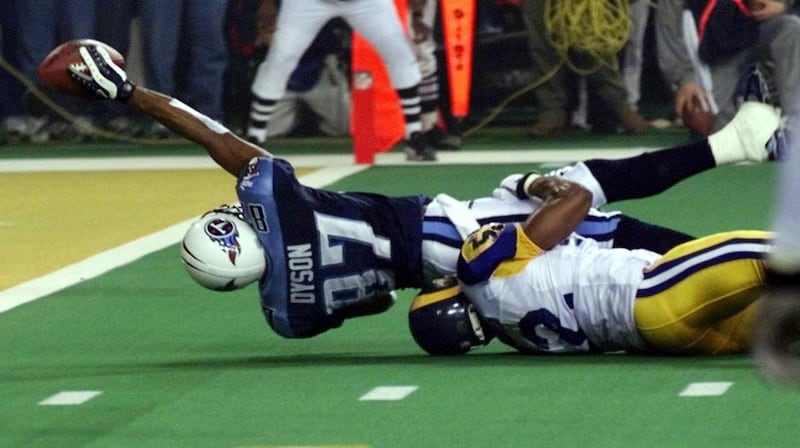

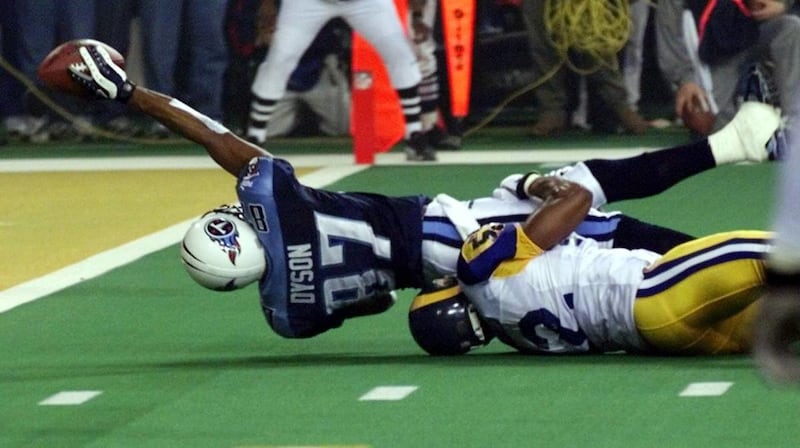

Dyson continued to watch as the NFL Network showed the play repeatedly from several angles in slow motion. Each time the result was agonizingly the same: He catches the ball at the 5-yard line and is tackled by Mike Jones one yard short of a touchdown on the final play of perhaps the greatest Super Bowl ever. Final score: St. Louis Rams 23, Tennessee Titans 16.

Every year about this time he can count on it. The play — which has become known as The Tackle — will turn up on TV, the Internet, newspaper pages and radio shows. Reporters will call asking him to relive each excruciating detail all over again. Dyson, the former Clearfield High and University of Utah football star, deals with it all patiently and politely.

The play has become part of the pop culture. During the 2000 presidential campaign, Al Gore, a senator from Tennessee at the time, said there was at least one Tennessean who wouldn’t come up “one yard short.” In the Tom Hanks movie “Castaway,” the Helen Hunt character refers to the play.

“I was sitting in the theater with my brothers (watching "Castaway") and heard that mentioned,” recalls Dyson. “The crowd started cheering. No one knew I was in there.”

Dyson is philosophical about the attention the play receives. After being taken in the first round of the 1998 NFL draft, he had visions of grandeur — 80-catch seasons, Pro Bowl selections, Super Bowl rings, the Hall of Fame. But circumstances derailed such ambitions — namely, injuries and the Titans’ conservative offensive scheme, which was built to run the ball.

“Not every player has a Hall of Fame career,” says Dyson. “For some of us, it just doesn’t work out due to circumstances. But to have something of a legacy, something you did that is remembered, that’s all you can hope for … I get asked about (The Tackle) a lot. It’s cool. I could have something NOT to talk about.”

Actually, Dyson left not one, but three plays that have been accorded legend status. On the penultimate play of Super Bowl XXXIV — one play before The Tackle — quarterback Steve McNair appeared to be sacked only to escape and fire a running bullet to Dyson at the 10-yard line for a 16-yard gain (let’s call it The Scramble). And then there is the Music City Miracle, in which Dyson caught a lateral pass on a kickoff return with 16 seconds left in a wild-card playoff game against the Buffalo Bills. Dyson ran 75 yards for a touchdown, winning the game and starting the Titans’ run to the Super Bowl.

Bleacher Report listed The Tackle No. 5 and the Music City Miracle No. 3 among the 10 most memorable plays in NFL history. Fox Sports and the New York Post listed The Tackle No. 4 among the greatest plays in Super Bowl history.

On a list of the 100 Best NFL Moments Ever, Men’s Health Magazine listed The Tackle at No. 7 and the Music City Miracle No. 4. ESPN listed The Tackle at No. 35 among the 100 most memorable moments in sports in the last 25 years.

On a list of the 100 best Super Bowl plays ever, ESPN placed The Scramble No. 20 and The Tackle No. 2. AskMen listed the Music City Miracle No. 9 among the 10 greatest moments in NFL history.

This week Sports Illustrated posted its top 100 Super Bowl photos. Dyson saw the post. “It was No. 3,” he says, referring to The Tackle.

What has eluded most observers is how central of a figure Dyson was in Super Bowl XXXIV. He had only one catch (for 9 yards) heading into the final 2 minutes of the game, but suddenly, with 1:54 and no timeouts left, down by 7, the Titans turned to him. They drove 87 yards in 12 plays and threw to Dyson four times, resulting in an incompletion and three catches. The game’s last six plays: a third-down, 7-yard completion to Dyson for a first down at the 31; a spike to stop the clock; an incomplete pass intended for Derrick Mason; an incomplete pass intended for Eddie George; a 16-yard completion to Dyson at the 10-yard line with 6 seconds left; and the famous 9-yard completion to Dyson that ended up at the 1.

The climactic final play was Double Zag Z Sliver Detroit (there also was a number in the play call for the protection, but 14 years later Dyson can’t remember what it was). The Titans had never used the play in a game, but they had practiced it several times successfully. The problem was, they had always practiced it in the middle of the field. At the 10-yard line, the field was shorter, the defensive zones compressed, meaning defenders didn’t have to cover as much ground.

Dyson, lined up wide on the right side, two yards outside of tight end Frank Wycheck, went in motion to the right tackle, then motioned back toward his original position. He did this to make it more difficult for a defender to jam him at the line and to see if the Rams were playing zone or man. No one followed Dyson’s motion.

“I knew it was coming to my side when I went in motion and saw it was zone,” he says.

At the snap, Wycheck ran a seam route (straight up the field), and Dyson cut underneath him on a slant. Jones, the Rams' linebacker, ran with Wycheck for several strides, but because the play was in the red zone, he was able to pass off the tight end to a shallower-playing safety sooner than he would have at midfield, freeing Jones to chase Dyson. Dyson caught the ball at the 5-yard line, but Jones immediately grabbed him around the hips and slid down to his knees at the 3. Dyson made a desperate lunge, extending the ball with his left hand toward the goal line, but he was about 18 inches short. He remained on his knees long after the play and the game ended, stunned and disbelieving.

Dyson owns a DVD of the game, but all these years later he still hasn’t watched it. “I will eventually,” he says. “I want to see what everyone else was watching. But I haven’ watched it yet because I know the ending. I know what happens. I would love to watch that game and know this time I’m going to score.”

Then on Sunday, with his son by his side, he found himself staring at the climactic play on TV and he couldn’t turn away. Watching the slow-motion replays, he saw something for the first time that he wishes he had done differently. If he had to do it over again, he would have pulled up tighter to Wycheck when he completed his motion, using the tight end to make it more difficult for Jones to follow him.

“I could have sneaked under (Wycheck),” he says.

Dyson has made his peace with the play; to come up just a half-yard short of a touchdown on one of the biggest stages in the world is a feat in itself. At least he was a part of something big. He knows this, but there is this other nagging thought.

“I can’t remember anytime (in football) that I didn’t get it done,” he says, “and then in the biggest game of my life and the biggest moment ...”

In the state championship game, he had an interception, a pass deflection and double-digit tackles for Clearfield High. In the Freedom Bowl, he’d caught the winning pass for Utah. In the wild card game, he’d scored the game-winning touchdown to beat the Bills. In the Super Bowl he came up less than a yard short of a ring.

For Dyson, it would never be better than the 1999-2000 Super Bowl season — his second in the league. The following season he blew out his knee after just two games. A year later, he returned to action and had his best season statistically, with 54 catches for 825 yards and seven touchdowns. But in 2002 he tore his hamstring 11 games into the season. After the season he signed as a free agent with Carolina, where he was supposed to pair up with fellow Ute receiver Steve Smith, but Dyson tore his Achilles tendon in practice that summer. He returned to play in the final regular-season game of the 2003 season, catching two passes and returning a punt. He went on to play in the Super Bowl with his new team, and, once again his team narrowly lost, this time 32-29 to the New England Patriots.

He never did win that ring. Nor did his brother, Andre, who, after playing four seasons with the Titans, two of them as Kevin’s teammate, went to the Super Bowl as a starting cornerback for the Seattle Seahawks — a 21-10 loss to the Pittsburgh Steelers in 2006.

“Oh for three,” says Dyson.

Dyson retired after the 2003 season. He was just 28, but the injuries had taken their toll and scared off NFL teams. He played in just 59 regular-season games, having missed almost two full seasons with injuries during his six years in the league. He finished with 178 catches for 2,325 yards and 18 touchdowns. Now 38, Dyson, who has two master’s degrees, is assistant principal and athletic director at Stewarts Creek High School in Smyrna, Tenn. He coached high school football for seven years, as a head coach and assistant, but gave it up.

“I’ll probably get back into, but I have two young kids and a wife, and I want to spend more time with them,” he says. “I had my time when football was my life. Priorities change.”

In his house there are several framed photos on the wall, including The Tackle. “It’s part of who I am, my legacy,” he says. “It was one of the biggest games in Super Bowl history. I played in two Super Bowls. There are lots of people who didn’t play in any. And then to be able to have something as memorable as that. I’ve always been humbled by it.”

Doug Robinson's columns run on Tuesdays and Wednesdays. Email: drob@deseretnews.com