LAREDO, Texas — The sound of fireworks celebrating Mexico’s Independence Day faded into the night just a few hours before Nicole, 21, and her uncle Josué, 23, from Honduras, arrived at the international bridge in Laredo, Texas. At 3:30 in the morning Monday, they were the first migrants to arrive for their hearings at a new tent court facility built to process asylum-seekers who were returned to Mexico under the Trump administration’s “Remain in Mexico” policy.

Fluorescent lights illuminated the concrete walkway where they stood, waiting for U.S. border officials in blue uniforms to escort them into the tents, which represent the latest attempt to solve what many have called an immigration crisis, caused by an influx of migrants from Central America.

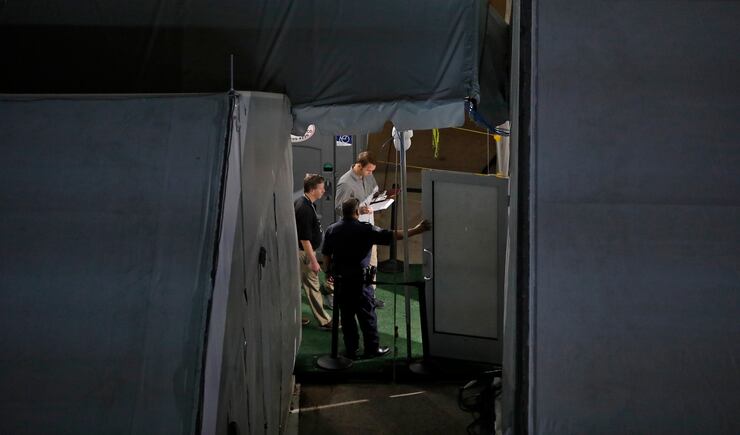

Nicole and Josué should have been exhausted — from the 12 blocks they walked in darkness from their hotel to the bridge, wary of criminals who prey on vulnerable migrants, from the two months they spent hiding out in Monterrey, Mexico, waiting for their court date, and from fleeing Honduras back in July. There, Josué’s brother was shot “acribillado,” or full of bullets, by gang members who then threatened the entire family. But despite getting little sleep, Nicole and Josué are wide awake with adrenaline in the pre-dawn hours, each clutching a stack of papers, folded and dirtied at the edges. (Nicole and Josué asked that their last names and hometown be withheld for their safety.)

Two sets of tent courts in Brownsville and Laredo, the very first of their kind, will cost $75 million for 18 months of operation. Inside, judges from other cities appear via video conference to handle asylum cases at the border. The facilities are a temporary solution to a problem that will not be easily resolved: an exodus of migrants from Central America escaping violence and instability in countries such as El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala. Whether the investment will pay off remains to be seen.

According to David Inserra, policy analyst for The Heritage Foundation based in Washington, D.C., the purpose of the “Remain in Mexico” policy and the tent courts is to weed out people who don’t have legitimate asylum claims and stop them from abusing loopholes that previously allowed them to be released into the United States.

“What we’ve been seeing the past few years are really high rates of people who get rejected or who don’t end up getting asylum in the end,” said Inserra. “The system is being overwhelmed by people who don’t have good claims. And that’s to the detriment of people who do.”

But immigration lawyers like Denise Gilman, a professor at the University of Texas at Austin Law School, say the tent court system hurts genuine asylum-seekers because staying in Mexico makes it extremely difficult for them to obtain legal counsel, travel back and forth to their hearings and stay safe during the monthslong process.

Since the “Remain in Mexico” policy was first rolled out in California in January, 41,000 migrants have been returned to Mexico, said Rick Pauza of U.S. Customs and Border Protection. On Monday, about 25 out of 50 people with scheduled hearings appeared at the football field-sized complex of white tent courts in Laredo, and four attorneys were present, according to Rep. Henry Cueller, D-Texas, who said tents were a waste of taxpayer money. Laredo city offered to let the federal government use a local building for just $1, but the offer was declined for reasons that are unclear. Judges in actual courtrooms in El Paso and San Diego already started hearing “Remain in Mexico” cases earlier this year.

Nicole and Josué, who said they feared for their lives after their entire family was threatened by gang members in Honduras, are lucky nonetheless. They have family in Austin who helped them hire a lawyer, and they have enough money to rent an apartment and wait in Monterrey, 135 miles away, without any income for the next several months. Their stacks of paper contained evidence their lawyer instructed them to bring: a death certificate for Josué’s brother that shows gunshot wounds as the cause of death, photos of his bloodied body and a newspaper article titled “Contractor dies in attack by hitmen.”

Alejandra Amador, 24, from Olancho, Honduras, arrived at the bridge much less prepared, without a lawyer, without evidence to support her asylum case and without realizing that the day’s hearing will be the first of many before a final verdict. Her 4-year-old daughter Natalie, wearing a bright pink bow and matching sweater, clung to her chest. Amador placed her hand over Natalie’s ear to block her hearing as she whispered that they ran away from home in July because the girl’s father was abusive.

“It’s not an option for us to go back,” Amador said.

To win asylum in the United States, applicants must show they have been persecuted based on race, religion, political affiliation or membership in a particular social group. Some lawyers have successfully argued that women qualify as a social group because of the overwhelming gender-based violence they face around the world, including Latin America and the Caribbean. Lawyers have also argued that families targeted by gangs, like Nicole and Josué’s, qualify as a social group.

But in June 2018, former attorney general Jeff Sessions overruled those precedents, cutting off asylum for victims of domestic abuse as well as gang violence, saying asylum definitions should not include “private violence.” The policy was blocked by a federal judge and remains void. Then, in July, the new attorney general, William P. Barr, issued a decision ending protections for migrants claiming asylum because their relatives have been persecuted, saying families do not qualify as social groups. Last week, the Supreme Court approved another policy that requires asylum-seekers who travel through other countries, such as Guatemala or Mexico, to seek refuge there before coming to the U.S.

Gilman says the tent courts are the latest move in this series of attempts to chip away at access to U.S. asylum laws, which date back to the end of World War II. Before those laws were in place, a German ocean liner carrying nearly 1,000 Jewish refugees asked for permission to land in Florida in 1939, but the Roosevelt administration refused. Many of those people returned to Europe and were killed.

“We are turning our backs as Americans on our international and domestic commitment to protect people who need protection,” said Gilman. “Decision after decision, it’s an overall effort to blockade and turn away asylum-seekers.”

While Inserra acknowledges some of the safety concerns and barriers to counsel associated with having asylum-seekers wait in Mexico for their hearings at the tents, he says these are not major problems.

“There are some additional difficulties, but the alternative difficulties are far, far worse,” said Inserra. “It’s much better than releasing people into the United States and having them wait two years for a court date in Connecticut, or something like that, where many of these folks won’t show up.”

“It’s much better than releasing people into the United States and having them wait two years for a court date in Connecticut, or something like that, where many of these folks won’t show up.”

The tents

At the end of the 1,000-foot bridge, the migrants turn right and Customs and Border Protection officers escort them through a metal door into the tent facility, which is built to handle between 200 and 300 people a day. A chain-link corridor with white plastic draped overhead empties into a large, air-conditioned waiting room where officials verify the migrants’ identities and screen them for medical issues.

Beyond, a series of courtrooms are equipped with TV screens, tables and rows of plastic chairs. Port-a-potties are placed strategically throughout the complex, including in the “juvenile waiting room,” which is full of colorful child-sized furniture, stuffed animals and books.

At their first hearing, the migrants are informed of their rights and educated about the asylum application process. They have an opportunity to tell an asylum officer why they are afraid to return to their home country or to Mexico. It is the first step in a long journey to winning an asylum case and earning permanent residence in the United States.

The tents and the “Remain in Mexico” policy are responses to a surge of Central Americans coming to the United States with their families. Historically, single adult men from Mexico made up the majority of illegal aliens coming to the U.S., but now over 60% are non-Mexican family units, according to a January statement from the Department of Homeland Security. In May, the number of migrants apprehended by Border Patrol after crossing the U.S.-Mexico border peaked at more than 132,000.

According to Andrew Arthur, a resident fellow in law and policy at the Center for Immigration Studies in Washington, D.C., invalid asylum claims have clogged the immigration court system, causing massive backlogs to the point that some asylum-seekers have waited years for their first hearing.

By bringing judges directly to the border via videoconference, the tent courts will allow asylum cases to be heard more quickly. People with valid claims will be allowed to stay in the U.S. and individuals without sufficient claims will be removed sooner, said Arthur.

Migrants are often exploited financially by “coyotes,” or human smugglers, or subjected to robbery and assault on their way to the United States, Arthur said.

“Young children especially are exposed to significant trauma as they come over the border,” said Arthur, who believes the “Remain in Mexico” policy keeps families safe by discouraging those without valid asylum claims from embarking on a dangerous journey.

Since “Remain in Mexico” was implemented, the number of people apprehended at the border has dropped by more than 38%, according to Border Patrol. Many migrants hoping to enter the United States have given up and gone back to their home countries, and the shelters in the Nuevo Laredo, Mexico, which were once overrun, are now operating at far below capacity.

Laredo Mayor Pete Saenz says these numbers are a sign that the “Remain in Mexico,” policy is working.

“The asylum laws exist, and there is a need for that, but 88% of asylum cases are rejected,” said Saenz. “Maybe the tent facility is not the best, but the fact that there is a credible, fair judge dispensing justice and hearing the cases, that’s what is important.”

Barriers

Ricardo de Anda, an asylum lawyer based in Laredo, said the tents may appear to provide due process, but in reality, they don’t create a viable path for serious asylum-seekers.

“They are taking a hatchet to our asylum system, making it next to impossible to be granted asylum,” he said.

The first problem is access to legal counsel. Because the city of Nuevo Laredo is so dangerous, lawyers like de Anda are not willing to travel there to meet with clients. He said that while he tries to offer advice over the phone, several hours of in-person interviews are required to build a strong case.

Marco Pacheco of Pacheco Couceiro Law Firm is one of a small number of Texas lawyers who has a license to practice in Mexico and an office in Monterrey, where many migrants who were returned to Mexico from the border are staying after being bused there by the Mexican government. Pacheco and his partner are representing about two dozen clients who will be appearing at tent court facilities.

“It’s a huge advantage for them to talk to American attorneys in Mexico,” said Pacheco. “Without a lawyer, their chances are next to nil.”

Having a lawyer is especially important now that the definition of who is eligible for asylum has been restricted, de Anda said. Those who don’t qualify for asylum because they travelled through Guatemala or Mexico first and did not try and claim asylum there may have to apply for protection under the Convention Against Torture, or Withholding of Removal, which require much higher standards of proof.

The second major hurdle is the danger posed to migrants staying in crime-ridden Mexican cities, where many face kidnapping and extortion at the hands of gang members.

“In Mexico, migrants are targeted, and they are a danger. We receive calls every week and people tell their stories of what they are going through in Mexico,” said Pacheco.

“In Mexico, migrants are targeted, and they are a danger.”

While it may take months to issue a final verdict in a case, even the most worthy asylum-seekers will remain in limbo in Mexico, often in unsafe conditions.

While Aaron Reichlin-Melnick, policy analyst for the American Immigration Council based in Washington D.C., says his ultimate hope is that the tent courts and the “Remain in Mexico” policy are dismantled, Inserra says the ideal outcome is for the tent courts to prove effective at dispensing verdicts quickly so genuine asylum-seekers can come to America as soon as possible.

“The best case scenario is that they do their job effectively and well, and in so doing, make it so people don’t just try to come here and use claiming asylum as their golden ticket into the United States, but instead only the people who are fleeing from active persecution, as defined in our immigration law, are the people who will try to come,” said Inserra.

Reichlin-Melnick, on the other hand, says there may be a way to balance the desire to ensure individuals who are trying to game the system are rooted out while still protecting those with legitimate claims and granting them the due process they deserve, but the “Remain in Mexico” policy isn’t it.

“Under the Migrant Protection Protocols, people with extremely strong asylum claims, who would be guaranteed to win if they were staying inside the United States, will not be able to win,” said Reichlin-Melnick. “Many, many people.”

At around 1:30 in the afternoon, Nicole and Josué were released from the tent courts and escorted back across the bridge to Mexico by U.S. border officials. Since entering the tents at 4 a.m., the sun had risen. In the daylight, the murky waters of the Rio Grande had become visible as well as the giant Mexican flag waving on the other side.

Leaving the white tent complex behind them, they returned to Monterrrey to await their next court date. Then, they will start the process all over again.