Herschel “Bones” Pedersen knew before he passed away this past week he would not have a funeral where a big throng would gather at the church, that his last remembrance would be a simple graveside service in American Fork with a few family members. In these days of a dark plague, this is how we do it.

In this regard, events of his 91 years of life will forever speak in Pedersen’s behalf. It will be a loud voice.

And in these times, it is needed.

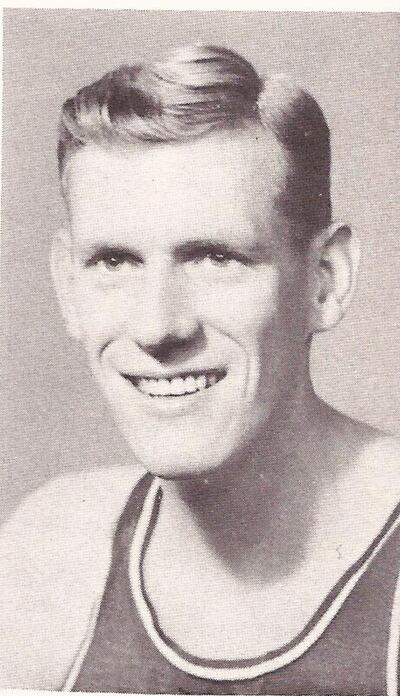

Pedersen was an iconic basketball player for legendary BYU coach Stan Watts in the mid-’50s who later became a modern-day biblical Paul, fearless and unashamed to preach his belief in God from Denmark to the blast furnace break rooms at Geneva Steel.

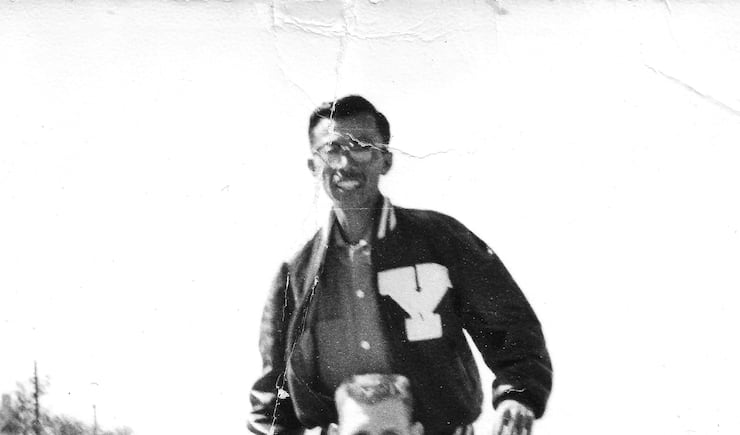

Pedersen was cut from his Granite High basketball team his sophomore and junior years, yet ended up leading his school to the state championship as a senior. Later he carried the Olympic torch when Utah hosted the 2002 Winter Olympics.

He was a gangly teen with long arms and legs and big feet, socially awkward and shy. He could catch pheasants and fish with his bare hands as a kid. He ended up playing guard then center for Watts after helping Denmark assemble its first Olympic basketball team as a missionary for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in 1949. He was an MVP basketball player and volleyball player for the U.S. Army, a privilege that kept him in Japan and away from the front lines of the Korean War.

He was a BYU defensive superstar, playing alongside Harry Anderson, Ed Pinegar, Dean Larsen, Sherm Crump, Terry Tebbs, Willard Hirschi and others. He developed into an offensive threat and big-time rebounder at 6-foot-5 and got in trouble with Watts — to the delight of BYU fans — as a showman on the court.

Bones set 17 records at BYU in his day, but most have been broken by a parade of All-Americans like Hall of Famer Kresimir Cosic, Danny Ainge and Jimmer Fredette. After one game in which Bones wooed the BYU crowd with his antics, the late Salt Lake Tribune columnist John Mooney wrote: “We don’t need the Globetrotters in Utah. We’ve got Bones Pedersen. He’s better than the Globetrotters.”

After being drafted by the St. Louis Hawks, who were owned by the Anheuser-Busch brewing company, the Hawks wanted Pedersen to hawk beer in commercials. He declined a big contract worth double what he’d make at Geneva. He chose to make steel rather than push beer and play ball. He turned down a contract of $25,000 to $35,000. In today’s dollar, that would be $242,000 to $339,000.

In a thumbnail, here’s what we glean from Pedersen’s near century on earth:

He learned two simple lessons of happiness. First, that belief, devotion and worship of a higher power lifts, elevates, transcends and makes everything in life more meaningful. Second, that belief in the worth of others, whether rich, poor, suffering, broken, faithless or famous, can propel one to serve them, and that single act has never-ending personal rewards and satisfaction.

As a result, being around Pedersen, people found a glimpse of how they could be happier and a better person.

Simple? Exactly. It was a talent.

Like many star athletes, Bones Pedersen cashed in on his popularity, like his stint in the Army and a foreman’s job at Geneva.

But Pedersen is a shining example to both athlete and regular father, husband, brother and son that there are far more valuable things in living a life than running around in fancy shorts.

Over the years, his fame as an athlete was replaced by what he did off the court.

Countless are the number of men at Geneva Steel who were lifted up by this “zealot” and “fanatic” who was not afraid to step up and offer a lifeline he knew worked. It turned some off but saved marriages, careers and souls of others.

The week his mother died was the same week he spoke at his mission farewell and left for Denmark. At that church service, scared, shy and wordless, he was never more terrified in his life. He felt guilty he had poached pheasants and sold them to rich folks in Salt Lake City. He hated speaking. He wondered if he was worthy. He stood up and managed, “Thanks for coming. Thanks for the money. God bless you. In the name of Jesus Christ, amen.”

Frustrated and discouraged months later in Denmark, he faced a life-changing moment when he decided to get up earlier than was required, study the language more intensely and examine in greater depth what he believed. If he didn’t experience a miraculous change in his faith and ability to speak Danish, he would return home. In this personal challenge, he ended up speaking fluent Danish and transformed into a talented teacher unapologetic and confidently projecting his beliefs.

“He set the tone for our basketball team. He began a tradition back in the day when players fouled out with four fouls. He would go to the bench and shake that opponent’s hand. Pretty soon the entire team was doing that and it lasted for years. He was a great man and his life reflected that.” — former BYU athletic director Glen Tuckett

The rest of his life, his voice was a tool as a teacher, mentor and counselor. Just weeks before his death and throughout the past year, while in his 90s, Pedersen entered the house of a neighbor, Doug Witt, who’d been sidelined with a nerve ailment after coming home from a project in Israel. He ministered to Doug, lifted him up, gave him kind words of encouragement, blessed and prayed with him, discussed gardening and sports.

“He spent time with me that was so valuable and so uplifting to me,” said Witt the night after Pedersen’s passing. “He could have just stayed in the comfort of his home at his age, but that is not him. He was remarkable in how he lived what he believed and loved others.”

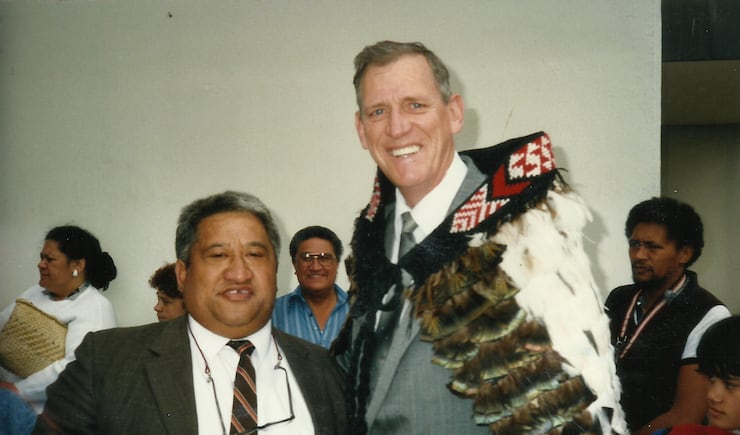

This is the same experience people had with Pedersen in Nova Scotia, Boston, Colorado, Arizona, California and Auckland, as well as in American Fork, as he worked in the Mount Timpanogos Utah Temple a few blocks from his home.

Pedersen believed in miracles. He saw them and sought them not just for himself, but for others.

“He was one of the most delightful guys we ever had at BYU,” said former athletic director Glen Tuckett. “He set the tone for our basketball team. He began a tradition back in the day when players fouled out with four fouls. He would go to the bench and shake that opponent’s hand. Pretty soon the entire team was doing that and it lasted for years. He was a great man and his life reflected that.”

Tuckett called Pedersen an effervescent and positive personality.

“He marched to the sound of a different drummer,” Tuckett said. “Sometimes I wondered if he was the only one in the parade.”

Pedersen once wrote, “In my life, I have seen miracles. As you go through life you have to ask questions. What must I do to gain the miracle I want? What am I not doing? What more could I do? Do these questions cause you to ponder, to think and to meditate?”

Working with Pedersen’s wife, Shirley, and his nine children, American Fork 37th Ward Bishop Matthew Lewis will conduct the graveside services at American Fork Cemetery. It’s a state requirement that the gathering be very small. There will not be another memorial service whenever the COVID-19 threat is over.

“My mother just wants this to be it, and let him rest in peace,” said his daughter Shelly Ebert.

“Herschel Pedersen is an inspiration and source of strength to so many in our community,” said Lewis. “His devotion to God and the gospel of Jesus Christ was unwavering and had a profound impact on my life and desire to be a better person. He will forever remain in our hearts.”

Bones, may you rest in peace.

For those who would like to watch the live stream of Herschel Pedersen’s graveside service on April 7 at approximately 11 a.m., you can log on to: https://www.facebook.com/groups/2733468120099008/

His obituary is at: www.warenski.com