In late 2016, Ammon Bundy’s cowboy boots went on trial.

While facing charges for his role in the armed occupation of the Malheur Wildlife Refuge in western Oregon, the controversial activist-turned-Idaho politician wanted to wear boots in the courtroom. The judge said no. For Bundy, though, it was important to wear authentic cowboy attire.

Criminal defendants in federal court wear shackles around their ankles — so, no boots allowed. But Bundy isn’t the type that’s easily deterred by government rules. “These men are cowboys,” Mr. Bundy’s lawyer argued, who also represented Bundy’s brother, Ryan. “Given that the jury will be assessing their authenticity and credibility, they should be able to present themselves to the jury in that manner.’’

The judge didn’t budge, and when Bundy finally appeared in her court, she made sure to survey his attire — a gray suit with white socks and loafers. “Very nice,” she remarked. To his lawyer, Ammon looked “comical.”

The jury ended up acquitting both the Bundys, loafers and all. But Bundy’s brush-ups with the law weren’t over. COVID-19 inspired a new chapter in anti-government politics, with Bundy as a central figure. Bundy has been arrested no less than six times protesting stay-at-home orders and mask mandates. He claims the state he now calls home, Idaho, has not experienced a pandemic, even as some 3,000 Idahoans have died due to COVID-19, and one study ranked Idaho as the least-safe state in protecting against the virus.

As the pandemic’s most recent wave ravaged Idaho, where Bundy is currently running for governor, I asked to meet with him. I wanted to understand what animates today’s anti-government posture behind so many vaccine holdouts, including Bundy himself. During our time together, one thing became clear: Ammon’s political stances are reflective of deeper tensions with the federal government.

While the anti-mask and anti-vaccination sentiments that exist within pockets of the West are most immediately about a pandemic, they’re also part of long-standing conflicts in places where the federal government still owns and controls a majority of the land.

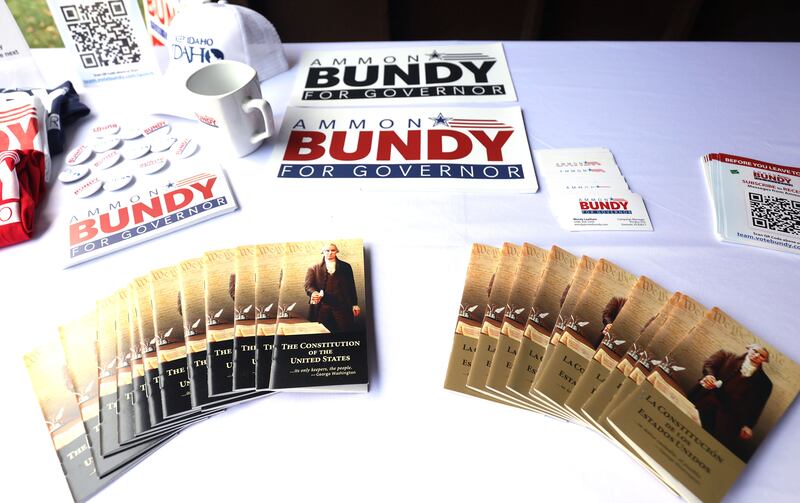

Surrounded by fall foliage, Bundy gives his pitch to a handful of potential voters under an Idaho Falls park pavilion. Leaning back on his boots, his face partially obscured beneath a wide brim hat, Bundy begins to recount his family’s story in the laconic cadence of a cowboy. Decades ago in southern Nevada, the Bundy clan lived in peace. The family farm produced hay and a handful of crops; their cattle grazed freely. “There’s very few people that live there, and my family has run cattle there since 1877,” Bundy says.

In fact, there are very few landowners in the area at all. It’s well known that the federal government is the largest landowner in the West, claiming over 50% of Western states, and more than 60% in Utah and Idaho. In Nevada, where Bundy grew up, that percentage leaps to 81%.

Cliven, Ammon Buddy’s father, with whom I spoke at length, was born the same year President Harry Truman established the Bureau of Land Management in 1946. And by 1975, when Ammon was born, Cliven was running hundreds of head of cattle on nearby federally owned land. He paid annual grazing fees to the Bureau of Land Management (BLM).

Things were fine. That is, until they weren’t.

In the early 1990s, environmental concerns led to a change in where and how Bundy cattle could graze on public land, and Cliven protested by refusing to pay his grazing fees (but continued to let his cows roam). Off-and-on legal battles persisted for two decades until things reached a boiling point.

By 2014, Cliven owed $1.2 million in unpaid grazing fees to the federal government, and in April, the Bureau of Land Management arrived to enforce the law and confiscate Bundy cattle. A handful of family members and friends came to defend the Bundys. They were engaged in a shouting match with federal agents when Ammon Bundy arrived on a four-wheeler.

Ammon described for me what happened next. A leashed German Shepherd lunged at him, and he kicked it. The dog lunged again, and he kicked it again. Then an officer lifted a stun gun and fired at Bundy, tasing him in the neck and chest. Bundy ripped out the prongs and continued toward the officers. They tased him again, and again, but he stayed on his feet. “It was pretty tense,” Bundy chuckled.

The BLM officers eventually retreated. “It’s all on video,” Ammon said to me, as if I wasn’t sold on the most shocking details. The raw video, which is still available on YouTube, can be hard to follow; nonetheless, it made waves among anti-government militia groups who began to flock to Nevada to support the Bundys. One man, who was later sentenced to 68 years in prison for his role in the standoff, admitted to being “hell bent on killing federal agents that had turned their back on ‘We the People.’”

A few dozen BLM officials came to hold 400 Bundy cattle in a makeshift corral when they were met with hundreds of protesters. A number of armed protesters assembled themselves on the overpass above the compound, aiming guns toward BLM vehicles. “I’m imploring upon you your responsibility to deescelate the situation,” a BLM agent told Ammon.

“We’re staying here until they’re gone,” Ammon responded. “That’s what we’re doing.”

The BLM pulled out soon thereafter, releasing the cattle. Ammon and his fellow protesters cheered. Ammon later called it a “miracle.” Cliven and Ammon were interviewed by Sean Hannity on Fox News, and national media flocked to Bunkerville.

The Bundys had won the day, but for Ammon, it was only the beginning.

Ammon Bundy chafes at the characterization of being “anti-government.” He’s not anti-government, he emphasizes; he’s anti unnecessary government or corrupt government.

Ammon’s decision to run for governor first came while he sat in solitary confinement in 2017, away from his wife Lisa and their six children, awaiting trial for his role in the Malheur Wildlife Refuge occupation and contemplating what he called the government’s “abuse and usurpation” of power. Bundy speaks candidly about how his “Keep Idaho IDAHO” campaign platform is inspired by what he saw when “the federal government came and surrounded my family’s home and threatened our lives” in Bunkerville.

Historian Betsy Gaines Quammen, an expert on the Bundys’ public lands fight, says this kind of rhetoric is what “we’ve heard from anti-government activists for quite a while. ... He will not say he’s anti-government, and yet he wants to strip it away.”

To Bundy, a strong Idaho economy centers on “taking back” federally owned lands. Turning public lands into residential areas is essential, he says, because cities are running out of space; the bigger and more congested the city, the more likely that “conservative, traditional values” will disappear. “It’s just what happens,” he said.

As Ammon explained it to me, the debate of who public lands belonged to emerged as the central issue of his campaign. Ammon (and his father) claim the federal government has no constitutional right to any land outside of Washington, D.C. When I brought up a counterargument — that the “Property Clause” in Article 4 grants Congress power to “dispose of and make all needful Rules and Regulations respecting the Territory or other Property belonging to the United States” — Ammon doubled down. A state is not a territory, he argued, so the clause does not apply.

Then I mentioned that the Supreme Court has ruled in favor of the federal government’s ability to own land, like in Kleppe v. New Mexico. Bundy insisted that his definitions of “territory” and “other Property” have never been considered by the Supreme Court. “I actually have a Constitution in my pocket,” he said, pulling out a pamphlet version published by the right-wing National Center for Constitutional Studies.

Cleon Skousen, who founded the NCCS and died in 2006, is an important figure in Bundy family politics, though Ammon looked puzzled when I mentioned his name. Skousen opposed most forms of government regulation and championed the privatization of public lands and national parks. Ammon’s father, Cliven, admits that he owes much of his interpretation of the Constitution to Skousen. “The Constitution is like scripture to me,” Cliven said, and when the Bundy ranch began having run-ins with the federal government in the ‘90s, it was Skousen’s writings that served as Cliven’s Constitutional study guide.

But when Cliven actually called Skousen for help during his conflicts with the feds, he asked him: “Cleon, where’s your army?” Skousen’s response was ambiguous: “They’re out there.”

Cliven was unsatisfied. “The federal government was coming after me. I felt that Cleon would have something better to tell me than just, ‘they’re out there,’ I guess.”

In late 2015, Cliven called his son, Ammon, who had recently moved to Idaho. A fellow ranching family — Steven and Dwight Hammond, of Harney County, Oregon — were wrapped up in a legal battle of their own, serving prison time on charges of arson. They set part of their property on fire to burn off juniper and sagebrush, a common ranching practice, but the fire had escaped their property and scorched over 100 acres of federal land.

“What do you know about the Hammonds?” Cliven asked. Ammon responded that he knew nothing. Regardless, Ammon Bundy didn’t hesitate to protest the perceived wrongdoing on the part of the federal government.

In November 2015, Bundy and another protester met with the Harney County Sheriff in Oregon and promised “civil unrest” if the Hammonds weren’t released from prison. In early January 2016, around 300 protesters — organized by Bundy and the Pacific Patriots Network, a regional militia group — marched through Burns, a quiet town of 2,700 people, demanding the release of the Hammonds.

At the conclusion of the march, Bundy hopped atop a snowbank and made an announcement. “Those who are ready to actually do something about it, I’m asking you to follow me and go to the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge,” he proclaimed. “And we’re going to make a hard stand.”

Greg Bretzing, the FBI’s special agent in charge in Oregon, was at the airport on Jan. 2, sending his college-age daughter off to Brigham Young University, when he received word that Ammon was headed to Malheur. “I was very familiar with the Bundys at this point,” he told me.

Ammon and his followers positioned guards and moved equipment to block off the ingress and egress roads to the refuge. Bretzing said the FBI was intentional to not provoke violence, and wanted to resolve the matter peacefully. Sensing the protestors’ distrust of federal agents, they used the county sheriff as a liaison instead of engaging with the protesters directly. “It was clear they were set up for a siege or an assault, and we made it clear we would not do that,” Bretzing said. “I believe, based on their actions in Bunkerville, they were looking for confrontation.”

Bundy, for his part, said they weren’t “harming anybody” or “endangering anybody.” When members of the Pacific Patriot Network and other militia groups offered help, Bundy turned them away, reportedly fearing the perception such association would bring. But the public image was already set, with some calling the group “Bundy’s Militia”; other descriptions were more colorful, like “Vanilla ISIS,” “Y’all Qaeda” or “TaliBundy.”

On Jan. 26, the FBI was informed that Ammon, Ryan and a handful of other leaders would be leaving the compound to attend a meeting in a nearby town. En route, a car carrying Ammon and Ryan was pulled over, and the pair was arrested; the other vehicle, driven by LaVoy Finicum, refused to stop and eventually crashed into a snowbank. Finicum resisted arrest and was shot and killed by law enforcement.

The officer was acquitted of wrongdoing. And, after time in federal custody and a lengthy trial, Ammon and Ryan were acquitted, too. The prosecution built much of its case on the charge of conspiracy to impede federal workers, one that proved difficult to substantiate. A jury voted to acquit the Bundys and a handful of other organizers, while 18 other Malheur protesters pleaded guilty or were acquitted of trespass or conspiracy — some serving time in prison, on probation or paying restitution.

“Ammon Bundy knew what he was doing there,” Bretzing said to me. “He knows he was breaking the law.”

The crux of Ammon’s activism is his belief in a genuine good-versus-evil conflict, and he believes providence is on his side. He claimed that God told him to go to Malheur, and while there, he and some fellow activists attended Sunday worship services at his faith’s denomination, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. But only two days after the takeover began, the church released an official statement.

“While the disagreement occurring in Oregon about the use of federal lands is not a Church matter, Church leaders strongly condemn the armed seizure of the facility and are deeply troubled by the reports that those who have seized the facility suggest that they are doing so based on scriptural principles,” the statement read. “This armed occupation can in no way be justified on a scriptural basis.”

But Ammon and his fellow protesters remained firm in their convictions. The good guys throughout history have never been the ones who used coercion, he told me. He then turned the topic of conversation back to what he believes is the latest example of government abuse: the pandemic. COVID-19 restrictions are “a great assault upon mankind,” in his view, and he feels so strongly that he’s been arrested again and again protesting stay-at-home orders and mask mandates in Idaho. In fact, he was issued a one-year ban from Idaho’s state Capitol (which expired in August) after being arrested twice in a 24-hour span.

Bundy believes herd immunity through mass infection is the only way out, as we learned from the “black plague or whatever,” he told me. Experts disagree: vaccination is the most effective way to inoculate against the most severe effects of the virus, they say, and the evidence of the vaccines’ effectiveness is overwhelming. But Bundy remains a skeptic — so much so that last April, he participated in burning a gigantic syringe sculpture in protest of “medical tyranny.”

At Ammon’s meet-and-greet in Idaho Falls, he offered a few prepared remarks, then pulled out his phone. “The Gem State Patriot News ran a poll the other day,” he said, before reading the results: Bundy held a massive lead — earning 62% of votes. What he didn’t mention was that the poll was conducted online and was for readers of the ultraconservative publication, Patriot News.

Others aren’t as bullish about his prospects. Incumbent Gov. Brad Little is expected to run for reelection. He’ll be challenged by his lieutenant governor, conservative firebrand Janice McGeachin. Seven other Republicans, including Bundy, have announced their candidacies. But, as of yet, Bundy is the only Republican candidate who has been disavowed by the state’s GOP chair.

“It’ll bring a dose of reality,” someone close to the Bundy family told me, commenting on his chances at election. “You think you have a lot of support with your cause, and then the polling numbers come in.”

What the polling numbers don’t fully express, though, is the very real discontent with the federal government that festers within pockets of the rural West. Lt. Gov. McGeachin is a prime example. When Idaho’s Gov. Little left the state last month, the lieutenant governor issued a rogue executive order, banning COVID-19 vaccine or testing mandates, even as Little had already issued a similar order, but had not included public schools.

In other words, as the White House was issuing its own vaccine mandate, Idaho politicians were falling over themselves to ban mandates and show how opposed they were to the fed’s actions.

COVID-19 has exposed deep fault lines running through not only America, but also swaths of the West. Cliven continues his refusal to pay the feds a dime in grazing fees, and Ammon is willing to be arrested six times in protest of public health safety measures. Voices like Bretzing and Quammen see the need for action against anti-government activists who flout the law. But as the COVID-19 death toll rises, the urgency of better relations between the federal government and its Western skeptics has rarely been more pressing.

After Ammon’s speech in Idaho Falls, I excused myself a few minutes early and thanked a campaign volunteer for arranging a leafy public park as the setting for the interview and the event. It was simple, the volunteer told me — they just made an online reservation for the pavilion, and then paid the government $100.

Editor’s note: A previous iteration of this story said that Bundy tied himself to a chair while protesting at the Idaho State Capitol. Rather, he refused to stand and was handcuffed by police.