Growing up, I envied my classmates. They could and would cite their heritage. Elio was Italian-American. Rachel was Irish. Maria’s grandparents had come to California from Spain via Mexico. The Jewish kids had family roots in Russia or Poland or Germany. They talked about going to Israel. I envied their pride in their heritage. I envied their comfortable connection to their ancestry.

As a Black American, I couldn’t do that. I had not the slightest idea from where my family had come. Africa, sure. But where? When? Who? No one in my family could trace our lineage back more than three generations. Then the trail ran cold. I’d found basic information about several of my great-parents in census records dating back to the 1870s. But, as other Black Americans discovered, I could find no family records from before the Civil War. Slave owners tended not to bother recording the births, deaths and parentage of their “property.”

In 2005, I was working as a correspondent for ABC News, then assigned to the Boston bureau. I came across a newspaper article about new genetic tests that scientists said made it possible to provide the ancestry of African Americans to a specific area of Africa. This new technology could cross-reference and connect one’s genetic code to a group of people in a distant land, which, essentially, is how the DNA test works. Only a few years earlier that would have been impossible.

My journalistic instincts kicked in — I knew this would be a terrific story to report. I pitched it to “Good Morning America” and they liked the idea. But the producers proposed something that had not occurred to me. They asked me to tell the story about the DNA tests through my own experience — they wanted me to take the genetic test and reveal the result on “GMA.”

I agreed.

I contacted African Ancestry, one of the early companies doing the tests, and Gina Paige, the president and co-founder, told me, “To really understand who you are as a Black person, you have to go back to the roots of who you are.”

“As African Americans,” she said, ”we don’t know where we’re from. We have a void. We’re the original victims of identity theft. We don’t know our original names. We don’t speak our original languages. We don’t know who our ancestors are.”

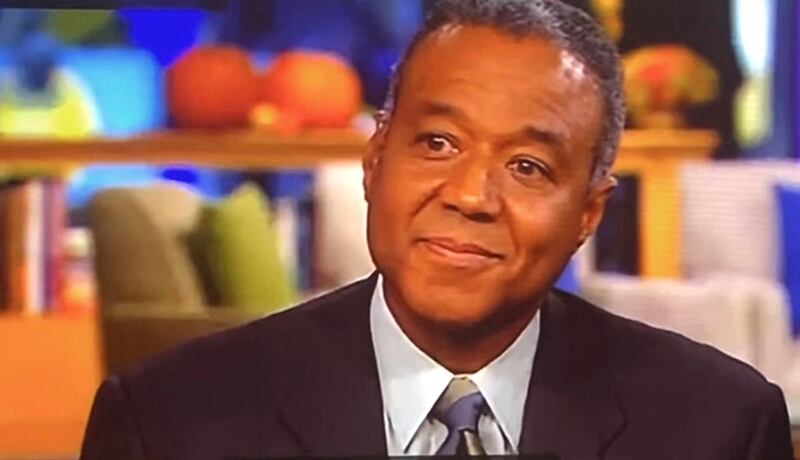

I was sent a test kit that included a cotton swab to take a saliva sample from my cheek. I sent it back and waited, anxious to understand who I was. A few weeks later, I was seated on the “GMA” set with the show’s co-anchor, Robin Roberts.

Robin introduced the edited piece I had prepared. It rolled. I watched but my mind was elsewhere.

When the story ended, Robin smiled at me. She said, “Are you ready?”

“I think so,” I said.

She spoke slowly, deliberately, drawing out the tension.

“And the results of the DNA test show that you are related to the Ashante people of Ghana.”

“Fragments of thoughts ricocheted through my mind, but one thought stuck — I wished my father were alive to share this moment.”

I said something, some words, but I was no longer there. My brain exploded into a kaleidoscope of thoughts and emotions. I was elated, yes, but also overwhelmed. It was almost too much to grasp. Fragments of thoughts ricocheted through my mind, but one thought stuck — I wished my father were alive to share this moment.

Long before we would call ourselves African Americans, my father had studied African history, politics and culture. He was deeply curious about our ancestral land and how we as a people connected to it. In the early 1960s, he had traveled to the then newly independent nation of Kenya, a rare thing for Black Americans in those days. He would have been so proud to know we were connected to the Ashante.

The segment ended and I left the studio, still dazed. I started walking. I kept thinking, Now you know. Now you know.

As I walked — I wasn’t really paying attention to where I was going — I started to form an image about my ancestor who was taken captive in Ghana, transported across the Atlantic, and arrived in America shackled and surely terrified, A stranger in a strange land destined to live a life in bondage. My joy was replaced by an anger that came on so suddenly it was unsettling. I was angry about the horrors that my ancestor had surely endured. I was enraged by the sheer unfairness of it.

That night, I decided to go to Ghana.

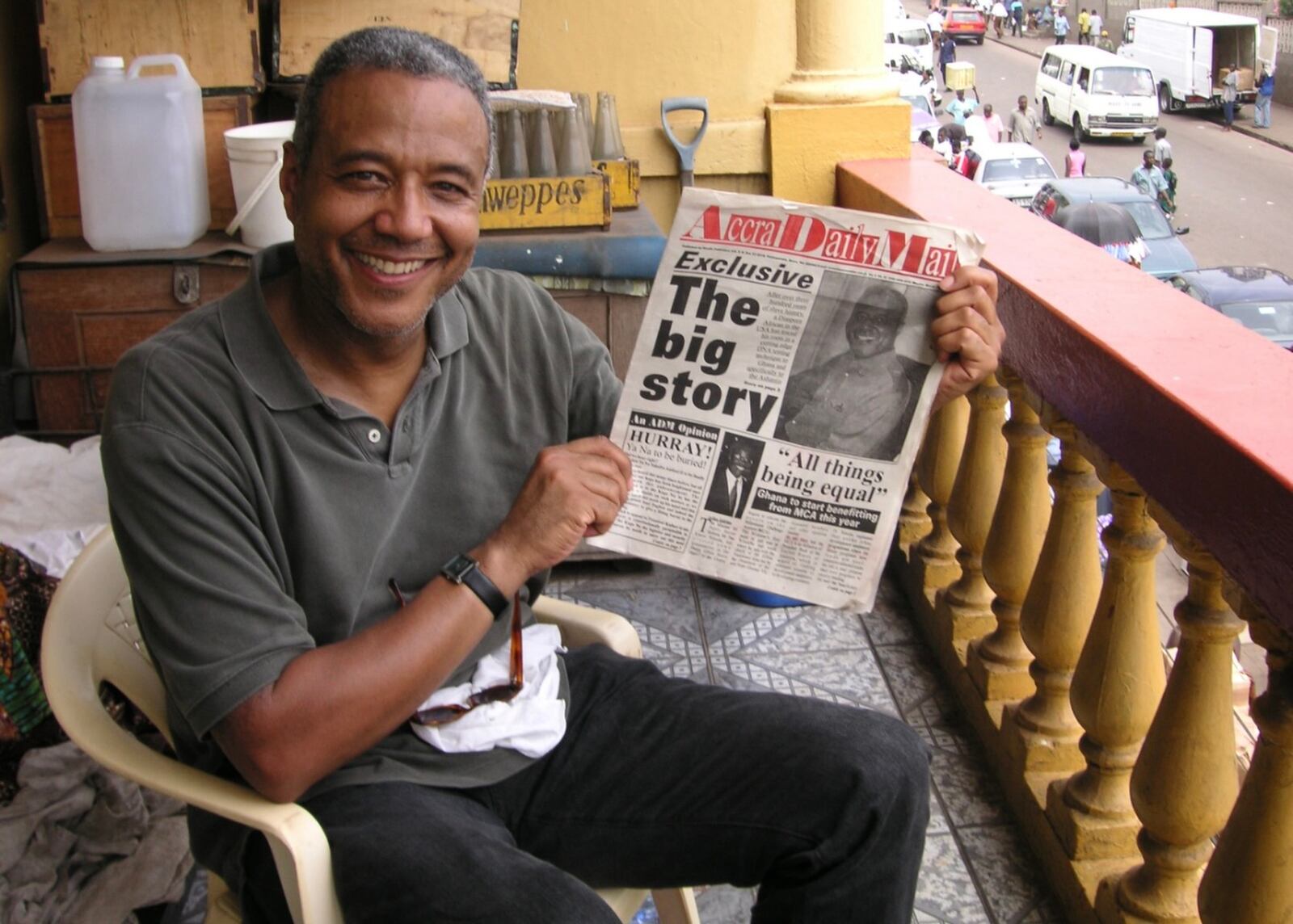

Three months later, I flew to Accra, the capital of Ghana. I was nervous with anticipation. I was also not quite sure what I was going to do when I got there. But I did have one contact. A friend had been riding in a taxi in Chicago driven by a Ghanaian immigrant. She called me and put me on the phone with him. He was friendly and eager to help. He insisted that when I went to Ghana that I visit his brother, Theophilus, who lived in Kumasi, the major city in the Ashante region in the interior of Ghana.

Accra was vibrant and colorful. Almost everyone was Black. It was strange and exhilarating. This was Mother Africa, really where my journey had begun. I was home.

I took a late-night bus to Kumasi. My seatmate expressed surprise, and was maybe even a little suspicious that a foreigner — especially an American with presumably the means to travel in greater comfort — would be taking the local bus. I told him I was in no hurry and I figured a bus would be a good way to get a feel for the country and its people. Luxury travel is fast. It is comfortable. But it’s a bubble, I said.

You’re on the inside looking out. I wanted to be outside that bubble.

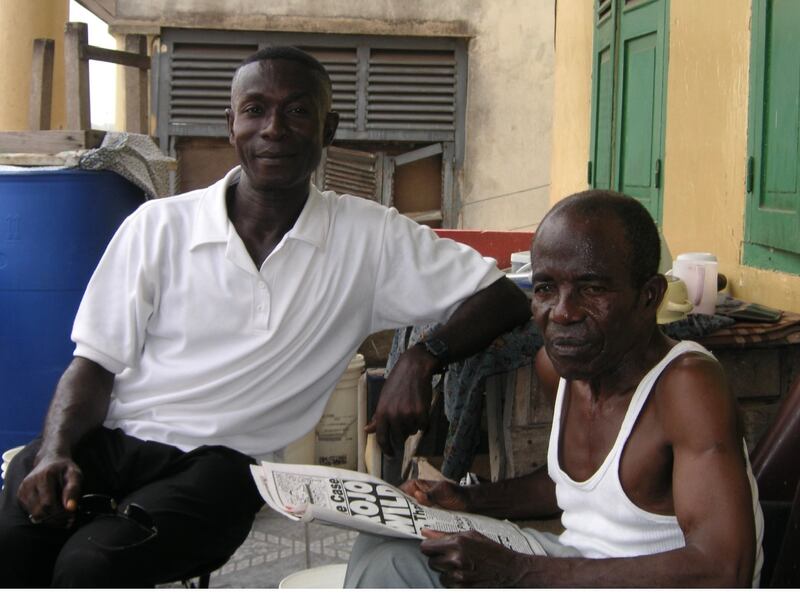

Theo Opoku met me the next morning at my hotel near the center of the city. He was short, powerfully built, and had an open, generous smile. For the next three days, Theo took me all over the city, explaining to me the traditions, customs and history of the Ashante. I had done some research but Theo taught me things about my people that research alone never could. The Ashante were a powerful tribe with a rich culture. When the British came in the 19th century to colonize what was then called Africa’s Gold Coast, the Ashante resisted. Over the ensuing decades, the two sides clashed repeatedly. The most powerful military in the world struggled to subdue the Ashante.

Listening to Theo’s stories, I felt something like what I had seen and envied in my classmates so many years before when they had proclaimed their ethnic pride. These were my people. Tough and independent. Unconquerable.

In the few days I spent with him, Theo became my teacher and my friend. He took me to local restaurants where I dined on dishes I’d never heard of. I met his friends and we told stories and laughed. Theo and I visited markets and a tranquil lake in the mountains outside of the city. He took me to the Ashanti royal palace. I visited his home and met his elderly parents. Theo taught me about Ghanaian day names — a nickname based on the day of the week you were born. I was born on a Thursday. My name day was Yaw or Yao.

On my final day, Theo surprised me by handing me a gift wrapped in thick paper. I opened it and found four carved wooden elephants in different sizes, I was deeply moved.

From Kumasi, I took a bus to the bustling coastal city of Cape Coast to visit the 17th century Portuguese fortress which had once been a transit station for the slave trade. The prisoners — some of them captured by Europeans; some by rival African tribes who sold them to the Europeans — would be held in dark, fetid cells until it was time for them to be taken in chains through a stone tunnel known as the Passage of No Return and loaded onto ships bound for the Americas. Between one and two million of the stolen Africans would not survive the brutal conditions and cruel treatment during the monthslong middle passage. Somehow, my ancestor had.

Once again, my imagination turned again to my distant ancestor packed away in the awfulness of the hold of a slave ship. I thought about the gripping fear, the bewildering uncertainty, and, surely, the aching despair.

I would end up spending a week in Ghana, mostly just walking through the streets, taking it all in, passing people and peering into their faces with what must have looked like a strangely intense curiosity. I would look at them and think, are we family?

“We were severed from our roots. We were set adrift.”

Probably for as long as humankind has existed, people have asked themselves: who am I? For Black Americans, this question can become a hunger — a desperate quest — because we are aware that we alone were systematically deprived of that knowledge.

A few years after my trip to Ghana, I was in a taxi in New York City. I looked at the driver in the rearview mirror. He had a horizontal scar beneath one eye. I asked him if he was from Ghana. He said yes. Was he Ashante? Yes, he said. But now he raised his eyebrows and stared at me. I explained that I had recognized the mark on his cheek as something many Ashante have. Soon we were chatting like old friends, telling stories and laughing easily. I told him about the genetic test, my trip to Kumasi and my lifelong search for what I had been missing.

When I got out of the taxi, the driver got out too. He came around the car. We stood there for a beat, looking at each other.

We shook hands, before snapping our fingers — Ghanaian style.

The driver looked at me and said, “You are family.”

Ron Claiborne previously wrote about his experiences in Ghana for ABC News. He retired from ABC News in 2018 after 32 years as a national and international news correspondent. He was also the news anchor of the weekend edition of “Good Morning America” for 14 years.