In terms of ideology, Orrin Hatch and Ted Kennedy couldn’t have been more different.

“One of the reasons I ran for the Senate was to fight Ted Kennedy,” Hatch once said of Kennedy, “who embodied everything I felt was wrong with Washington.”

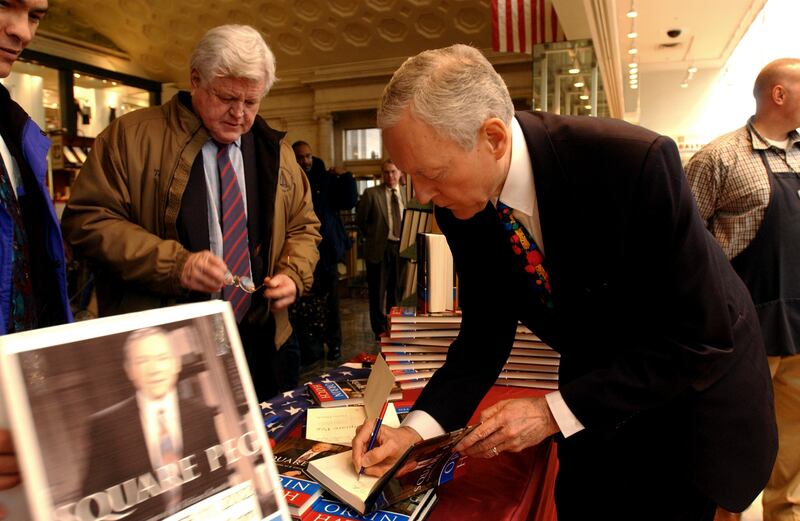

But through the 1980s and 1990s, the two men became the yin and yang, the oddest couple of American politics — the disheveled, überliberal, hard-partying, superrich libertine Ted Kennedy of Massachusetts, and the abstemious, buttoned-up, conservative church-bishop-from-a-poor-family Orrin Hatch.

And sometimes, they shaped American history together.

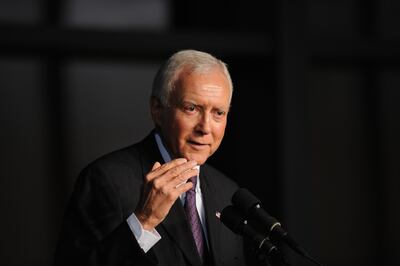

In fact, if greatness is measured by achievement, Hatch was the greatest United States senator of the past half century. This is not a partisan or an ideological opinion; it is a judgment based on empirical fact.

According to scholars at the nonpartisan Center for Effective Lawmaking, a research institution hosted jointly by the University of Virginia and Vanderbilt University, Hatch is the number one “most effective” senator of all Republicans and Democrats from 1973 (the year the center’s data begins) to 2019, when measured by the center’s “Cumulative Legislative Effectiveness” score that adds up legislative effectiveness across a member’s entire time in Congress. The number two spot in the ranking? None other than Kennedy, Democrat from Massachusetts.

“One of the reasons I ran for the Senate was to fight Ted Kennedy, who embodied everything I felt was wrong with Washington.”

“We did not agree on much, and more often than not, I was trying to derail whatever big government scheme he had just concocted,” recalled Hatch in 2009. “And, in those years that Republicans held the majority in the Senate, when it came to getting some of our ideas passed into law, he was not just a stone in the road, he was a boulder. Disagreements over policy, however, were never personal with Ted. I recall a debate over increasing the minimum wage. Ted had launched into one of his patented histrionic speeches, the kind where he flailed his arms and got red in the face, spewing all sorts of red meat liberal rhetoric. When he finished, he stepped over to the minority side of the Senate chamber, put his arm around my shoulder, and said with a laugh and a grin, ‘How was that, Orrin?’”

After countless knock-down, drag-out battles on the Senate floor and in committee rooms, Hatch remembered, “We’d both reach out for each other and hug each other.”

Hatch died last April at the age of 88; Kennedy died in 2009 at the age of 77. The brotherly bond the two shared, despite their sharp ideological differences, barely exists in Washington today.

“When I came to Washington, I hadn’t the slightest idea that I would eventually have a strong working relationship with and love for the man that I came to fight,” Hatch recalled in 2018. “And if you would have told me that he would become one of my closest friends in the world, I probably would have suggested that you need professional help.”

A turning point in their relationship occurred in 1981, when Hatch took over the chairmanship of the Labor and Human Resources Committee, which was dominated ideologically by a 9-7 majority of Democrats joined by two liberal Republicans. Hatch needed Kennedy’s assistance to get anything done, because Kennedy largely controlled the committee’s votes. “I went to Ted and said, ‘I’ve got to have your help,’” Hatch later explained. “And to his credit, he did help. And we became friends.”

“When we got together,” Hatch remembered of his work with Kennedy, “people would say, ‘Oh, gosh, if those two can get together, anybody can,’ and they’d get out of the way.”

According to Kennedy aides Nick Littlefield and David Nexon, “The beauty of an early bipartisan alliance is that it provides at least some measure of instant credibility on both sides of the aisle. When Hatch and Kennedy signed on to a compromise, it gained instant credibility. They were so far apart on the conservative-liberal spectrum that when they agreed on a bill, it immediately had the potential for broad support. Hatch would sometimes joke that the only way they got together was that one of them must not have read the legislation. Hatch was a particularly desirable co-sponsor because once he agreed to join with Kennedy on a piece of legislation, he was a tenacious advocate.”

In 2009, Hatch remembered Kennedy as a powerful force of opposition, but also of possible cooperation on certain shared causes: “Well, he was the leading liberal in the United States Senate for all the years I’ve been in the Senate. I’ve been there 33 years. And bar none, he was the leader. And he had more control over the Democratic Party base than anybody else. He’s the only one who could bring them along on issues that were down the middle and really bipartisan, but he could bring them along. They would have to listen to him.”

“If you would have told me that he would become one of my closest friends in the world, I probably would have suggested that you need professional help.”

“Ted was a lion among liberals, but he was also a constructive and shrewd lawmaker,” Hatch once recounted. “He never lost sight of the big picture and was willing to compromise on certain provisions in order to move forward on issues he believed important. And, perhaps most importantly, he always kept his word.”

Hatch’s willingness to work with Kennedy sometimes earned him sharp criticism from fellow conservatives, both in public and in private. The National Review, a conservative journal, described him as a “latter-day liberal,” and in closed-door Senate meetings, fellow Republican Sen. Phil Gramm often teased Hatch by calling him a “flake” with liberal, left-wing ideas. Hatch was undeterred, once explaining, “Whenever I can move him (Kennedy) to the center on something that really makes a difference in people’s lives, why shouldn’t I?”

For many years, the two senators sat next to each other in the Senate’s Education and Labor Committee room, where smoking was allowed until the early 1990s. “You could always tell when Teddy and I were in an argument or were fighting, by the amount of cigar smoke that he blew my way,” as a nonsmoking Mormon, Hatch remembered. “If there was a particularly strong disagreement, he would just sit back in his chair, puffing smoke my way, giving me an actual headache to go along with the political headaches he gave to all of us on the Republican side.”

Sometimes, Hatch recalled, “Teddy would lay into me with the harshest, red meat, liberal rhetoric you could imagine. But just minutes later, he would come over and put his arm around me and ask, ‘How did I do, Orrin?’”

At one point in the 1980s, Hatch was so alarmed at Kennedy’s self-destructive habits of partying, womanizing and drinking that he confronted his friend. “Ted, it’s time for you to grow up and quit acting like a teenager,” said Hatch. “You know what you’ve got to do, don’t you? You’ve got to quit drinking.” Kennedy seemed “very stunned” by the intervention, according to Hatch, and gently replied, “I know.” On another occasion, Hatch said, “I’m going to have to send the Mormon missionaries after you.” Kennedy looked away and concurred, “I’m ready for them.”

Their friendship intensified over the years, to the point that the two resembled battling brothers who cherished a deep love for each other. Kennedy went to the funeral of Hatch’s mother, and when Hatch attended the service for Kennedy’s mother, he tried to slip into the back of the church, but Kennedy beckoned Hatch to join him in the front row.

David Kessler, a medical doctor who served as a health policy adviser to Hatch in the 1980s, observed what he saw as “an extreme personal fondness and an extreme degree of caring” between Kennedy and Hatch. Kessler recalled seeing Hatch speak of Kennedy “with a fondness that transcended anything that I had seen.”

Sometimes it seemed that for much of their time together in the Senate, which spanned from 1977 to Kennedy’s death in 2009, Kennedy and Hatch were fighting each other like gladiators on issues such as spending bills, foreign policy and judicial appointments. But other times, they were fighting together, shoulder to shoulder to move America forward on great issues like disability rights and AIDS funding, and on two of their proudest achievements — religious freedom and health insurance for poor children.

One day in 1984, a drug and alcohol abuse counselor named Alfred Leo Smith attended a Native American religious ceremony in Oregon.

What happened there caused him to be fired from his job, denied unemployment compensation and forced into a seven-year legal struggle that culminated in a stunning decision by the U.S. Supreme Court.

It also inspired Hatch to forge the proudest bipartisan achievement of his life, with — you guessed it — Ted Kennedy.

“He never lost sight of the big picture and was willing to compromise to move forward issues he believed important.”

Smith was a Klamath Nation tribal member who endured years of homelessness and alcoholism but had been sober since 1957 with the help of Alcoholics Anonymous. Part of his job at a nonprofit drug and alcohol treatment center was to learn about Native cultural and spiritual practices that could aid his work, such as sweat lodges and spiritual ceremonies. When his co-worker Galen Black was invited to a Native American religious ceremony and then summarily fired by the center for ingesting a small amount of ritual peyote, a mescaline-containing hallucinogen derived from cactus considered sacred medicine to Native American practitioners, Smith was indignant.

Native Americans had used peyote in such ceremonies for 5,500 years, and some believed that the ritual could help in recovery from addiction. Smith resolved to attend an upcoming ceremony himself, but his bosses told him that if he ingested peyote, he would lose his job, too. Smith’s immediate response was, “You can’t tell me that I can’t go to church!” He wondered, “How could they tell me I was attending a drug party when the ceremony was one of the most sacred Native American ceremonies that has survived for thousands of years?” Smith went to the ceremony, ingested a small quantity of peyote, told his employer about it and was fired. He and Black applied for unemployment benefits, but the state denied the claims on the basis that ceremonial use of peyote, then technically criminal in Oregon, was “misconduct.” An Oregon state court ruled that their conduct was safeguarded by the First Amendment and ordered the state to pay them their benefits. The state refused, appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, and demanded that the two men confess to engaging in misconduct and repay the court-mandated unemployment they’d already received.

Some people advised Smith to seek an out-of-court settlement with the state. He woke up one morning and told himself, “Your kids are going to grow up and the case is going to come up one of these days and someone will say, ‘Your dad is Al Smith? Oh, he’s the guy that sold out.’” He decided, “I’m not going to lay that on my kids. I’m not going to have my kids feel ashamed. Even if we lose the case, they are going to say, ‘Yeah, my dad stood up for what he thought was right.’”

In taking his stand, Smith was exercising the most fundamental of all American freedoms, the one chosen by the founders of the United States to be expressed in the very First Amendment to the Constitution, which guarantees the freedom of religious worship by specifying that “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” The Supreme Court had ruled that the clause applied to both federal and state governments.

It was a principle that dated back to the first European settlers on the continent, including citizens in the Dutch outpost of New Amsterdam, which was later called New York. In 1657, they protested against religious discrimination in a declaration called the “Flushing Remonstrance,” which is considered to be a precursor to the Bill of Rights, which declared that “the law of love, peace and liberty” extends to “Jews, Turks and Egyptians” as well as “Presbyterian, Independent, Baptist or Quaker.”

Freedom of worship was also a principle that was very dear to the heart of Orrin Hatch, an intensely religious man who began each day by reading scripture. He once explained, “Daily prayer and scripture study remind me of the principles in which I believe, the reason why I am here, and what I should be fighting for. This puts things in the right perspective and allows me to focus my efforts on what really matters.” Hatch even saw the possibility of a divine hand guiding his career. “I actually believe I was destined to do this,” he once explained. “I’m not saying it was divinely sanctioned, but it could very well have been.”

Jace Johnson, Hatch’s onetime Senate chief of staff, recalled that if a weighty decision presented itself, Hatch would say, “Why don’t we just kneel down and pray right here? And let’s get our answer.” Johnson recalled being “really shocked” by Hatch’s faith, his belief and his ability to call on spiritual guidance when needed. “It blew me away,” Johnson remembered. In a 2017 tribute to her father, Hatch’s daughter Marcia spoke about his compassion to others, even those who disagreed with him. “I know he believes that all children are children of our Heavenly Father and he treats them that way,” she said. “He does this, I believe, because he is striving to be like our Savior Jesus Christ. I know he has great love for him and for his gospel and for all mankind.”

Hatch once explained how he saw the relationship between religion and politics. “Every issue in government to me involves morality,” he said in 1980. “Every issue involves folkways and mores; every issue involves religious belief and nonreligious belief. There is no such thing as a purely political issue that doesn’t involve alternative beliefs of various people.”

“Whenever I can move him to the center on something that really makes a difference in people’s lives, why shouldn’t I?”

Hatch’s own faith, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, had been subjected to prejudice, discrimination and periodic mob violence. In 1906, a U.S. Senate committee recommended that a Republican U.S. senator from Utah, Reed Smoot, a Latter-day Saint who was elected to office in 1903, be declared ineligible to serve amid false allegations that members of the church took a secret loyalty oath to the church over the nation and that they still practiced polygamy in secret, despite its renunciation by the church in 1890. On February 20, 1907, Smoot’s ordeal, which he endured with dignity, finally ended when a vote by the full Senate to expel him failed. He served until 1933, a full 30 years in office. It was, in effect, a trial of his church, and in the words of the Senate historian’s office, “The U.S. Senate took a stand in support of religious freedom for all Americans.”

Throughout his career, Hatch would prove steadily consistent on the subject of freedom to worship. In 2010, when a private organization announced plans to build an Islamic center and mosque on private property near ground zero in downtown Manhattan, drawing protests from many Republican leaders and others, Hatch defended the group’s right to do so. “The only question is are they being insensitive to those who suffered the loss of loved ones?” Hatch asked. “We know there are Muslims killed on 9/11 and we know it’s a great religion.” Hatch said that even if public opinion was against building the mosque, “that should not make a difference if they decided to build it and I’d be the first to stand up for their rights.” Religious freedom as expressed in the First Amendment was a concept strongly endorsed by virtually every American president and politician since the nation’s founding, and it was repeatedly upheld by the nation’s courts. When Alfred Leo Smith’s case was finally ruled on by the U.S. Supreme Court, he had every reason to expect that the Oregon courts’ rulings in his favor would be upheld.

In its 1963 Sherbert v. Verner decision, the U.S. Supreme Court had established a legal test for courts to follow when considering unemployment compensation claim denials that might be affected by the First Amendment’s religious free exercise clause: The government must prove it is acting to further a “compelling state interest” in the manner least restrictive, or least burdensome, to religion. This did not appear to apply in the Smith case.

But in a surprise decision on April 17, 1990, the Supreme Court stunned legal observers and managed to shock and alarm Hatch as well as liberals, conservatives, the religious community and civil liberties advocates. In the case of Employment Division, Department of Human Resources of Oregon v. Smith, a majority of the justices held in favor of the state of Oregon’s denial of unemployment claims for Smith and his colleague.

By declaring that the free exercise of religion did not protect minority religions from “neutral, generally applicable laws,” the court effectively abandoned the Sherbert test and rewrote the prevailing interpretation of the First Amendment. “They contend that their religious motivation for using peyote places them beyond the reach of a criminal law that is not specifically directed at their religious practice,” wrote Justice Antonin Scalia, but the “free exercise of religion” did not shield minority religions from “neutral, generally applicable laws” — even if those laws were developed by an indifferent or ignorant majority. In other words, the court held that the free exercise clause protects religious beliefs but does not exempt religious actions from laws unless the laws specifically target a religion for unfavorable treatment. The “compelling state interest” test no longer applied.

Smith was especially dismayed by the ruling, saying, “I think it was a horrendous decision, like they drove a spike through the Bill of Rights. If the First Amendment doesn’t protect me, how in the hell is it going to protect you?”

Both religious leaders and civil liberties advocates alike realized that the Smith decision could be applied widely to threaten all religious-freedom claims. A powerful, unlikely cross-ideological coalition quickly mobilized to seek a solution in Congress. Their fears were well-founded: In the two years after Smith, a Congressional Research Service analysis reported federal and state court decisions were being made that limited all kinds of religious exercise claims. Within months of the Supreme Court’s Smith decision, congressional Democrats introduced legislation to counteract it.

In the Senate, both Hatch and Kennedy decided the Smith ruling posed a danger to religious liberty. “The compelling interest test has been the legal standard protecting the free exercise of religion for nearly 30 years,” Kennedy later said. “Yet, in one fell swoop the Supreme Court overruled that test and declared that no special constitutional protection is available for religious liberty as long as the federal, state or local law in question is neutral on its face as to religion and is a law of general application.”

Hatch and Kennedy worked together to develop legislation that would effectively negate the Smith decision, restore the Sherbert test, and strengthen protection for the free exercise of religion. The Hatch-Kennedy bill matched a bill introduced in the House of Representatives by then-Rep. Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y. It was a brief 797-word law called the Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993 (commonly referred to as RFRA) that declared, “Laws ‘neutral’ toward religion may burden religious exercise as surely as laws intended to interfere with religious exercise,” and “Governments should not substantially burden religious exercise without compelling justification,” and the “compelling interest” test should be restored.

In closed-door Senate meetings, fellow Republican senator Phil Gramm often teased Hatch by calling him a “flake “with liberal, left-wing ideas.

The legislation quickly attracted support from a wide range of groups on the left and right. “When the American Civil Liberties Union and the (conservative) coalitions for America see eye to eye on a major piece of legislation,” noted Hatch, “I think it is certainly safe to say that someone has seen the light.” Hatch fought hard for the bill alongside Kennedy and defended it against protests from anti-abortion activists who feared that it would allow women to claim a religious right to abortion and state authorities who worried that prison inmates would demand luxury treatment because some invented religion required it. But Hatch insisted that if exemptions were allowed, the bill would fall apart. In 2013, he recalled that “Republicans and Democrats were united on one fundamental principle, that the right of all Americans to the free exercise of their religion should be equally protected by the same rigorous legal standard. We refused to give an advantage to some religious claims or to prevent others from being considered.”

On the Senate floor, Hatch argued for swift passage of the bill in its unadulterated form: “This bill involves the rights of every American citizen. The Smith case was wrongly decided and the only way to change it is with this legislation. Mr. President, I hope this legislation is not amended in any way, because religious freedom ought to be encouraged in this country. It is the first freedom mentioned in the Bill of Rights. And, frankly, that is what Senator Kennedy and I are arguing for here today with a wide, vast coalition across the country that believes in restoring religious freedom to the point where it was before the Supreme Court decision in Smith.”

As was the case in many such bipartisan bills, Hatch’s support gave nervous or wavering Republicans the political “cover” to back it. The bill was approved by a unanimous voice vote in the House and a 97 to 3 vote in the Senate, and then-President Bill Clinton signed it into law in a White House Rose Garden ceremony on November 16, 1993, with Hatch and other members of Congress standing behind him.

In 1997, the Supreme Court ruled that RFRA applied only to federal — not state or local — laws, and Hatch responded by spearheading congressional passage of the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act (RLUIPA). The law protected all religions’ right to build church facilities on private property, and it was signed into law by Clinton in September 2000. Additionally, 22 states have passed RFRA-like laws of their own, and state courts in an additional 10 states have strengthened religious liberty protections.

Over the past 30 years, the religious freedom laws championed by Hatch have proved to be durable, vital instruments for protecting the free exercise of religion in the United States and have been successfully invoked by religious minorities including Orthodox Jews, Muslims, Sikhs and Native Americans. Through the laws, a Sikh accountant was permitted to pass through security at a federal building while possessing a religious kirpan, a small dull dagger that is a symbol to Sikhs like the cross is to Christians. A group of Native Americans obtained an exemption from federal law to possess eagle feathers in spiritual ceremonies. Observant Sikhs were enabled to serve in the U.S. military with their religious beards and turbans. A group of Buddhists overcame a zoning challenge to residential gatherings for silent meditation, and a Presbyterian church in Washington, D.C., overcame a zoning challenge to its program of feeding thousands of homeless citizens, enabling it to continue.

In recent years, the philosophy advanced by RFRA has come into conflict with the views of LGBTQ advocates, who object to protections that enable, for example, religiously affiliated organizations or companies to deny medical coverage for birth control or abortion or deny service to gay customers. Recent Supreme Court decisions in the Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores (2014) and Masterpiece Cakeshop, Ltd. v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission (2017) cases have sharpened this tension and led Democrats to propose legislative exceptions to the RFRA framework. Hatch strongly opposed any revisions to the original law he authored with Kennedy in 1993, asserting, “The day we begin carving out exceptions to RFRA is the day RFRA dies.”

In 2018, Hatch said if he had to pick “one bill that I love more than anything else,” it would be the Religious Freedom Restoration Act. “We could not pass that today,” he said. “That has protected religious freedom like never before. It’s something you would think you wouldn’t have to protect, but believe me, you have to protect it.”

In the years after the passage of RFRA, Hatch and Kennedy continued to work closely together, most notably in 1997 with what came to be known as the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP). The final version of the bill hiked the federal excise tax on cigarettes by 43 cents a pack, to raise $10 billion over five years to reduce the federal deficit and over $20 billion for children’s health insurance to be distributed not through a new federal bureaucracy, but through block grants to the states. Hatch and Kennedy shaped it so it could not be considered an entitlement, which reduced potential Republican opposition, and they cleverly attached the proposal to an emerging agreement between Republicans, Democrats and the Clinton White House to reduce the deficit.

The two senators unveiled their plan at a press conference at the Children’s Defense Fund in Washington, D.C. It was the biggest expansion of the nation’s social safety net since the launch of Medicaid in 1965. Hatch explained that he proposed the bill to demonstrate that the Republican Party “does not hate children,” and he added that “as a nation, as a society, we have a moral responsibility” to provide coverage for vulnerable children. “Children are being terribly hurt and perhaps scarred for the rest of their lives” when they don’t have health insurance, he noted.

“Religious freedom ought to be encouraged in this country. It is the first freedom mentioned in the Bill of Rights.”

For the next 144 days, Hatch and Kennedy fought together to bring the bill to a vote. At first, Hatch remembered, “Our bill upset everyone.” It faced opposition from conservative critics, tobacco companies and their congressional allies — and especially from Republicans. Republican Senate Majority Leader Trent Lott, of Mississippi, immediately condemned the bill, saying, “A Kennedy big-government program is not going to be enacted,” without mentioning Hatch. According to Hatch, when he told Lott the bill would pass, Lott replied, “No, it isn’t.” Hatch’s fellow Republican senator from Utah, Robert F. Bennett, first promised his support, then publicly backed off. At this, Hatch declared, “I am disappointed, but I accept whatever my colleague wants to do. As for me, I am going to fight my guts out for these kids.”

“There may not be two more relentless legislative advocates than the Utah Mormon and the Massachusetts Democrat,” wrote The Wall Street Journal’s Al Hunt. The bill, Hunt reported, “is driving Mr. Lott and Oklahoma Sen. Don Nickles, the Senate GOP whip, crazy. They demagogue it as big government and tax-and-spend, misrepresenting what it would do. And they are strong-arming every Republican in sight to oppose it.”

Days after the bill’s passage, a New York Times headline announced, “Through Senate Alchemy, Tobacco Is Turned into Gold for Children’s Health.”

According to an account in the Deseret News, “Delegates to the 1998 Utah GOP Convention actually passed a resolution condemning Hatch’s children’s health insurance program. In a show of defiance, Hatch took the stage and lectured the 5,000 hard-core GOP delegates on the responsibility of man helping fellow man.”

The SCHIP program created by Hatch and Kennedy went on to serve many millions of American families and earn near-universal praise from politicians in both parties and from state governors across the country. In 2018, as one of Orrin Hatch’s final acts in Congress, he helped secure full funding to continue the program for another 10 years.

In 2008, Ted Kennedy was diagnosed with brain cancer. One day, Hatch’s chief of staff, Jace Johnson, got a call from his counterpart on Kennedy’s staff, who said, “Listen, Ted’s getting to the point where he’s probably not going to be able to be in the Senate much longer. We have him in a really convenient office over in the Capitol off of the Senate floor. Could the senator come by and meet with him?”

Johnson related what happened next: “And so, Sen. Hatch and I went over there, and I sat down as the two of them, and Ted Kennedy’s two dogs that were with him, sat down with him and sat by the fireplace and (they) just talked about this long career that they had shared in the Senate. And it was incredible how much they remembered about all the things that they had worked on together. Children’s health insurance, labor laws, they could just go through the list of all these areas where they had partnered, religious freedom, they knew all the bills and all the laws that they had done together and how they had kind of fought these wars in their mind and did it for the good of the country. I love that moment. And at the end, they stood up and I took a picture of the two of them that I still have today, and, tearfully, tearfully, you know, (we) walked out. … It was well over an hour in there and the two of them just talking. They really cared about each other.”

Hatch offered a tribute to Kennedy at his memorial service at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum on August 29, 2009. He called Kennedy “one of my closest friends in the world,” and added, “Like all good leaders, when he struck out on a mission, he was able to inspire many to follow him until the job was done, no matter how long it took or how hard the task was.” Hatch concluded by telling Kennedy’s widow and his assembled family and friends, “I miss fighting in public, and joking with him in the back room. I miss all the things I knew we could do together.”

William Doyle is an award-winning, New York Times bestselling author. This story is excerpted from his book “Titan of the Senate. Orrin Hatch and the Once and Future Golden Age of Bipartisanship,” published by Center Street, Hachette Book Group Inc., copyright 2022.

This story appears in the December issue of Deseret Magazine. Learn more about how to subscribe.