A Western monarch butterfly weighs less than a dollar bill, its wings more fragile than a house of cards. Its life span is similarly delicate — averaging only two to five weeks.

But these feeble six-legged jewels make the most of their short time during their migration into Utah from Arizona, California and Mexico. During their short stopover, monarchs hugely impact our ability to farm. Without them and other pollinators, we would no longer have chocolate, apples, coffee or many flowers. In fact, nearly 75% of the food crops worldwide depend on pollinators like monarchs. And currently, the Western monarch is facing an existential threat.

Conservation and stewardship have long had broad support. In fact, the Endangered Species Act passed unanimously in the Senate in 1973, “with all the friction of a proclamation honoring the troops,” according to Kate Wall of the International Fund for Animal Welfare.

Even today, according to reporting from The New York Times, at least 80% of Americans, including 74% of self-identified conservatives, support the act. Hunters, farmers, anglers, private landowners, recreationalists and environmentalists rarely agree on much. And while we may disagree on how we ought to protect the creatures of the earth — as Wall puts it — “few of us believe that society shouldn’t protect animals at all.”

But how we’re protecting them is changing. Historically, the bulk of North American conservation has been built on the paradigm that the best way to manage wildlife is to sustain things where they are, as they are. “But increasingly, we’re realizing that, in an era of changing climate and disturbance regimes, it’s not going to be possible to keep everything the way it was, where it was,” says Jonathan Coop, a forest ecologist at Western Colorado University.

So as our natural world changes, how are field scientists and conservationists changing their approach to save the species that have so long defined the West?

The Southwestern ponderosa pine — which has romanticized in films, songs and minds across the West for decades — is an example of an iconic species under existential threat. With the growing frequency and intensity of forest fires, the trees are struggling to survive and reproduce. Their populations will likely continue to struggle as their habitats grow drier and western pine beetles spread. And if we lose ponderosa pines, the savannas of pine trees in the mountains of the Southwest will lose their anchors. It will lead to a loss of grasses and shrubs that deer and elk feed on, as well as leading to erosion that will wipe out soil and the nutrients it holds.

With that grim reality in mind, conservationists are thinking more about what ecosystems will probably look like in the future and are working with those long-term adjustments in mind. In terms of the ponderosas, it’s clear to Coop that, in a lot of places, “these forests just don’t really have much of a future where they now are.”

But it’s difficult to think about the future without up-to-date records and research of sensitive species and their patterns from the past. “These are really big questions that we don’t even have the science to support,” Coop says.

Experimental data is limited, so it’s difficult to know whether these large interventions, like transferring tree populations to different places, are the “right” thing to do. Here’s the only certainty: To leave the ponderosas as they are is to risk their existence.

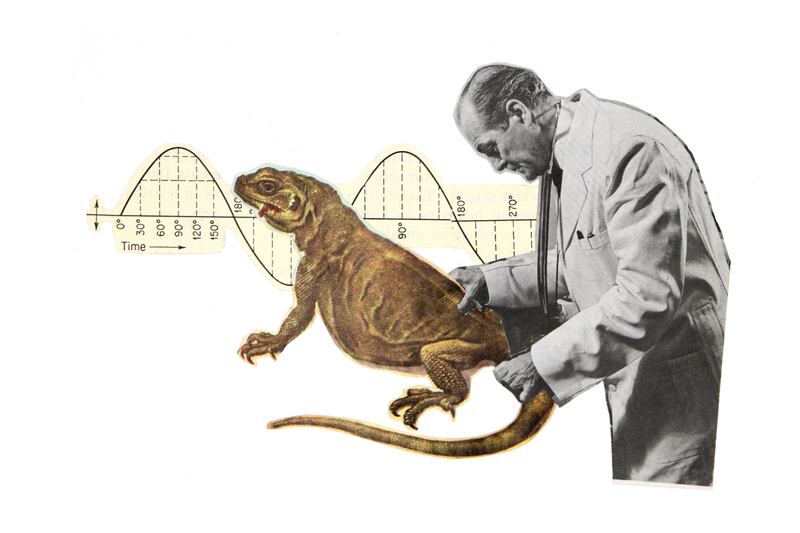

Gary Nabhan, a desert ecologist at the University of Arizona, faced that exact conundrum when working with chuckwallas. A group of these large lizards were living on islands off the Gulf of California — islands that the rising ocean was slowly but surely swallowing up.

Chuckwallas are often culturally important to Indigenous communities, and so to save this threatened species Nabhan and his collaborators worked to move some of the population to rocky outcrops near the coast on mainland California. They chose the new habitat specifically for its similarities to the islands. Since then, chuckwallas have settled well into the rugged coastline.

Helping species move to alternate habitats, called translocation or assisted migration, has been a concept in conservation for decades. Other contingency strategies include stocking seed banks, collecting DNA from plants and animals for future restoration possibilities, and breeding species in captivity to bulk up population numbers before releasing them back to the wild — a strategy that famously worked for the California condor.

But all these methods, Nabhan says, should be last-ditch efforts. Zoos and seed banks cannot “save” a creature, he says, because “the genes are just part of the story, that’s not what the whole species is.”

A big part of what makes a species, he adds, is how it interacts with the “whole landscape,” and the catalog of wildlife around it. If those ecological relationships are lost for good, Nabhan says, those species become relics, and those species are almost as good as extinct.

Take the sub-globose snake pyrg, a tiny aquatic snail that lives exclusively in the springs of Utah’s Snake Valley. Discovered only about 25 years ago, these teeny water mollusks are about the size of poppy seeds and act as important filters for spring water — they feed on algae and decaying plants and keep water oxygen levels in check. But groundwater pollution, wildfires and the influx of invasive fish species threaten the pyrgs’ populations.

The pyrgs act like a proverbial canary in a coal mine for water quality in the springs. When biologists noticed a dip in their numbers in 2019, the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources and the Bureau of Land Management decided to take active measures to remove nonnative fishes and monitor water quality. Since the species is found in just one location, the sub-globose snake pyrg is vulnerable, but worth saving in the eyes of the state of Utah.

For Gloria Tom, the director for the Navajo Nation Department of Fish and Wildlife, the need to protect and restore habitats has always felt urgent. She’s held her current role since 1998, and says in Indigenous communities, there’s no space for climate pessimism.

“The Navajo people live and breathe natural resources as part of their everyday life, and so we have to look at the changes in an optimistic fashion and always move and strive towards improving the landscape in spite of what’s happening,” she says.

The priority for them, adds Tom, is to fight to preserve the landscape as it is — whether that means limiting hunting permits, adding water-collection infrastructure to fight drought or sectioning off land from human use. The northern leopard frog, for example, is not listed as endangered on federal registries, but it is endangered by Navajo standards, meaning the prospects of this species’ survival on Navajo land is in jeopardy.

Every year, the Navajo Nation Department of Fish and Wildlife surveys the lakes, rivers and wetlands to count the number of frogs on its land. Based on those dwindling numbers documented by Indigenous field scientists, the Navajo Nation has prohibited human disturbances and developments in proximity to those habitats. This is one of the cases when documentation in research and intervention are able to work together.

As of right now, no one seems to have an answer for how to save certain species. “A lot of times, the only way we can really learn what’s going to work is by trying it out,” says Coop — a somewhat troubling reality given that “the decisions that we’re making now are going to have implications for hundreds, if not thousands of years.”

That could mean trying to save the ponderosa pines and still losing them, or the iconic Western monarch migration dwindling to nothing more than folklore. But scientists, as well as government agencies, are willing to put in the time and money to make the best decisions that they can for the future, now.

To accommodate the need for long-term planning, the National Park Service created the Resist-Accept-Direct framework to aid conservationists as they are “responding to ecosystems facing the potential for rapid, irreversible ecological change.”

With the framework, NPS says that land managers can choose to either resist ecosystem change by restoring conditions where change has occurred, accept change by allowing ecosystems to drift into new and unprecedented conditions (often with uncertain consequences), or direct and facilitate ecosystem transformation toward desired conditions.

Land managers can theoretically apply this framework to everything from individual species to whole landscapes. Using whatever data on sensitive species available, they can then decide how to best balance the resources they have with the likelihood of different outcomes.

But different species and parcels of land fall under the responsibilities of different bodies and agencies, resulting in a patchwork of initiatives and outcomes across the West. Decision-making will need to be “very deliberate,” Coop says.

The imperative now is to conduct those experiments and collect ecological data for the conservationists of the future. The more data scientists can collect on species’ resilience to different environmental conditions, how they rely on each other and how those relationships change climate variation, the more precise and deliberate conservationists can be in their future decision-making.

Additionally, bringing communities together with as much information as possible sets us up for the best chances of success, says Coop. After all, he says, conservation science is about “involving people to answer meaningful questions that help us have good lives and be good inhabitants of this planet.”

But the answers to those questions will continue to lie in research, action and preservation of the creatures of the West, before they’re gone.

This story appears in the February issue of Deseret Magazine. Learn more about how to subscribe.