Temperatures in the West are returning to more winterlike conditions after an unseasonably warm start to the year.

But it’s not just the few weeks of 2022 that felt a bit warmer than normal, data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration shows. And climate scientists say it will take more than a cold snap and some late-season snow this year to reverse the impact of a yearslong trend.

“Warm temperature records are outpacing cool temperature records,” said Karin Gleason, a climate scientist at NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information. “It does vary month to month, but the overall trend is that we are seeing warm records set more frequently than cold records.”

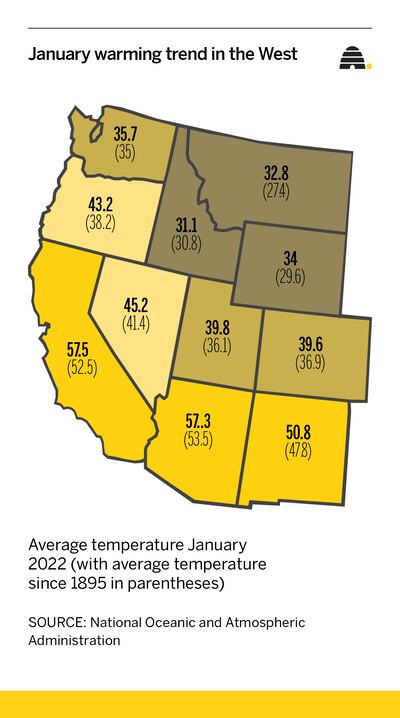

Every state in the West, including Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, Washington and Wyoming, has seen above-average temperatures every January since 2018.

Since 2000, 11 out of 22, or half of all Januarys, have had temperatures over the historical average in every Western state.

February is also looking to be one of the warmest on record in the West, according to experts, although official data won’t be released until early March.

And December records were smashed in Montana, Washington and Wyoming, signaling the region was in for a warmer than usual winter, data shows. Montana also had the most unseasonably warm January in the West with the month’s average temperatures being 5.4 degrees over the historical average.

Warmer winters, even by a few degrees, can mean disaster for snowpack, which the West relies on for year-round water.

Now with a warm start to this year, scientists like Daniel Swain, an atmospheric climate scientist at the University of California, Los Angeles, are concerned about what this means for the megadrought the West has already been experiencing.

“Warm temperatures and climate change have essentially made (the megadrought) about 40-50% worse than it would have been,” he said. “In fact, so much so that it probably wouldn’t have been considered a megadrought at all if it were not for the warming that we’ve observed and the increasing loss of water through evaporation back into the atmosphere.”

While unusually warm or record temperatures at any time of the year can be disruptive, a few degrees of variation around the freezing threshold of 32 degrees Fahrenheit, which is “super sensitive to even relatively modest shifts,” has “huge implications” for the rest of the year, Swain said.

“Winter is the time of year when there exists this specific temperature threshold, you’re either above or below freezing,” he said. “And if you transition from one side to the other of that threshold, you start to see huge, enormous changes.”

That variation means what should be snow is now rain, which depletes the West’s snowpack supply, thus throwing the region into the throes of drought and increased wildfire risk due to dry vegetation and soil.

“Early spring thaw enhances the depletion of the reserve of water before summer when it is needed most,” Gleason said. “Warmer temperatures mean more evaporation, which dries out vegetation, forests and depletes the soil of moisture. This can enhance the intensity and duration of drought periods and contribute to enhancing the wildfire season.”

Record highs for January

| State | Fahrenheit temperature | Year set |

|---|---|---|

| Arizona | 63 | 2003 |

| California | 63 | 2014 |

| Colorado | 45.4 | 1986 |

| Idaho | 39.7 | 1953 |

| Montana | 39.7 | 2006 |

| New Mexico | 55.9 | 1986 |

| Nevada | 52.6 | 2003 |

| Oregon | 46.3 | 2015 |

| Utah | 46.2 | 2003 |

| Washington | 42.6 | 1953 |

| Wyoming | 40.1 | 1981 |

Gleason said climate change is modifying the overall “temperature neighborhood” we live in by moving the average temperature up and changing the odds for experiencing more warm extremes.

The West is one of the top regions in the country that is warming at a faster rate than the rest of the U.S., she said.

The region recently experienced whiplash from unseasonably warm weather right back to cold winter weather — a variability that is indicative of the increasing effects of climate change, Swain said.

“The Earth is not warming evenly — certain places, seasons and even times of day are warming faster than others,” nonprofit climate analysis group Climate Signals said. “Climate change has led to more frequent warm winters in the Western U.S. while the Eastern U.S. experiences cold winters.”

This trend is part of the bigger picture of climate change that people need to be aware of, Swain and Gleason said.

“Any one month or even any one year isn’t enough to tell us about where things are headed in the long run,” he said. “In terms of the temperature records, for better or for worse, we’re all together for the same ride globally. It’s a global problem that’s going to require a global solution.”

Nobody in the West can afford to ignore the consequences of a warming winter that are happening now, Swain said.

“This is something that’s emerging as a really important and urgent conversation that we’ve put off for many years hoping that things would get better on their own,” he said. “Instead, over that period, they actually got worse. It has really gone from being predictions about the future from a couple of decades ago to being realistic about the present.”

On an individual level, Swain said it’s time to talk about climate change with friends and family in common conversation, even in the context of winter sports like the Olympics or the shrinking of the Great Salt Lake.

”What we need to do is be demanding better choices and the ability to make better choices from a climate perspective,” he said, “and make it much easier for people to make choices that are good for the climate and good for their communities at the same time.”

K. Sophie Will is a Deseret News data and graphics contributor. @ksophiewill