Kids ate better, families paid down debt and parents were able to improve their work-related skills when the expanded child tax credit was being sent directly to American families.

That’s according to a Brookings Institution global working paper released this month that examines the now-defunct expansion, which was paid monthly for six months. The report, “The impacts of the 2021 expanded child tax credit on family employment, nutrition and financial well-being,” takes data from the Social Policy Institute’s Child Tax Credit Panel Survey.

The nationally representative panel included 1,782 American parents who were eligible for the credit. The survey also had a comparison group of 2,015 ineligible households. The assessment was based on a survey wave right after the final payment was received.

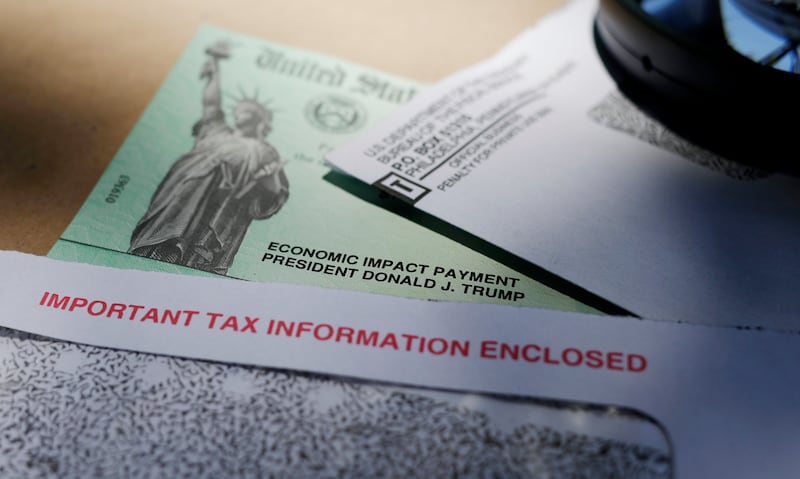

As part of the American Rescue Plan, Congress temporarily boosted the $2,000 child tax credit to $3,000 for income-eligible families for children ages 6 to 17, or $3,600 for younger children. For the second half of 2021, payments were sent monthly to most eligible families. And the credit was made refundable, so families with little or no earned income qualified, which isn’t normally the case.

When 2021 ended, so did the expanded tax credit, though tax filing season just ended and many are collecting the half that was to be paid as a lump sum.

The report found that families typically used the monthly payments “to cover routine expenses without reducing their employment. Eligible families experienced improved nutrition, decreased reliance on credit cards and other high-risk financial services and also made long-term educational investments for both parents and children.”

The changes were “especially promising” for low- and moderate-income families, as well as Black, Hispanic and other minority families, according to the report, which was led by researchers from Appalachian State University, Washington University in St. Louis, the University of North Carolina Greensboro and the Urban Institute.

Among common uses for the monthly payments:

- 70% paid routine household expenses like housing and utilities.

- 58% bought clothing or other essentials for their kids.

- 56% bought more food for the family.

- 49% set some money aside for emergencies.

- 42% paid off debt.

The researchers didn’t find statistically significant employment changes for either those who were eligible for the monthly payments and those who were not. But the authors noted that eligible households were 1.3 times more likely to start working on learning new professional skills, compared to those ineligible for the tax credit.

“Low- and moderate-income families eligible for the (tax credit) were also more likely to report learning professional skills, more likely to report improvements in their ability to manage emergency expenses and less likely to report using high-cost financial services like payday loans and auto title loans, relative to CTC-ineligible families,” the report said.

More than 6 in 10 of those who received monthly payments said it was easier for them to budget, compared to receiving a tax credit in a lump sum after filing their taxes. And a report by the Niskanen Center said the payments were particularly helpful to folks in rural communities.

But according to Vox’s Dylan Matthews, “there’s a simple answer to why the child credit didn’t continue: There weren’t 50 senators willing to support the extension. And most public reporting suggests the main holdout was Sen. Joe Manchin.”

Manchin, a Democrat from West Virginia, has tanked a lot of the social policy proposals in Biden’s Build Back Better framework. As for the child tax credit, he reportedly wants a $60,000 household income cap and a firm work requirement, Axios reported.

“Some reports have also suggested that Manchin thought the money would go to buy drugs — an evergreen concern about cash programs for the poor (Manchin’s office declined to confirm or rebut that he expressed this concern privately),” wrote Matthews. “This suspicion is ill-founded; the best evidence review on the question I know of concluded there’s little reason to believe cash transfers increase drug or alcohol abuse.”

Others have expressed worries that the child tax credit, without work incentives, would actually provide a disincentive to work. Sen. Marco Rubio, R-Florida, for example, pushed for the larger credit, but doesn’t believe families should receive the credit if they don’t make enough earned income, as the Deseret News reported in January.

A working paper by researchers at the Becker Friedman Institute for Economics at the University of Chicago in October predicted not having a work requirement “would lead 1.5 million workers (about 2.6% of all working parents) to exit the labor force.” That, in turn, would reduce the gains made in cutting child poverty, they said.

Others, including Greg Nasif, spokesman for the bipartisan nonprofit advocacy organization Humanity Forward, think the payments were a huge help in strengthening families — and boosting employment.

“We’ve never seen a government program that operates this efficiently,” Nasif told the Deseret News. “It gets money directly to the people who need it. It’s reaching well over 90% of the people it’s intended to support. Families are using it to feed their kids better. They’re using it to go back to work. By putting the money towards childcare expenses, that frees them up to work more hours. There’s been a marked growth in the number of low-income people who are self-employed, starting new businesses, expanding nonprofits, etc.”