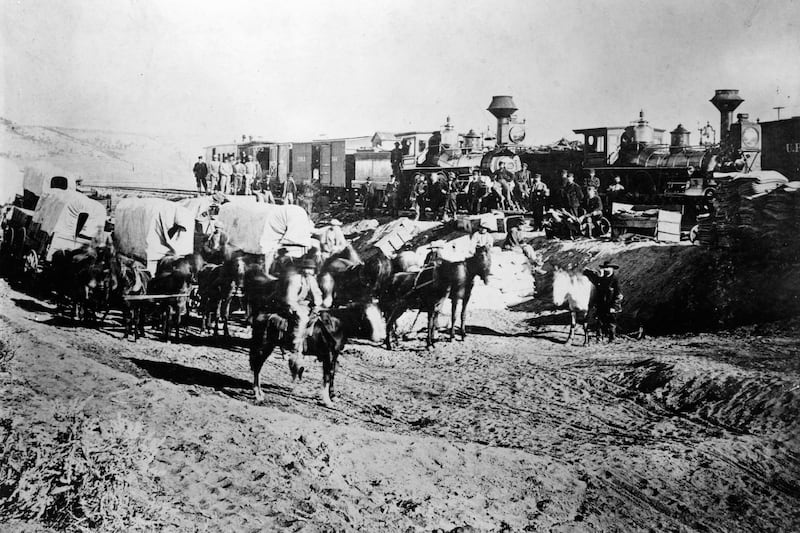

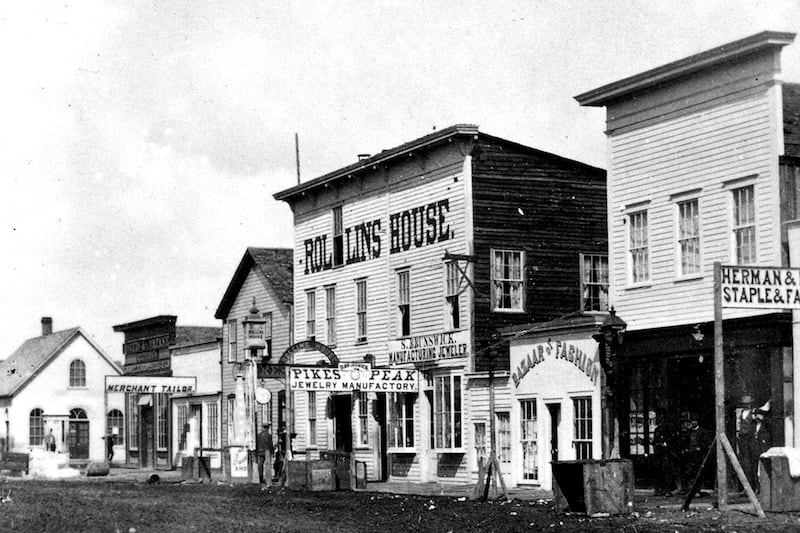

The state of Wyoming evolved out of the Pacific Railroad Act of 1862, which called for the construction of a railroad to connect the eastern and western United States. By July 1867, settlers were already arriving, and Gen. Grenville M. Dodge, chief engineer of the Union Pacific, began the survey for a city at Cheyenne, which would become the capital of the state. It was to be four miles square with well-organized blocks, alleys and streets. The Union Pacific, the beneficiary of a huge land grant from the government as an incentive to get the railroad constructed, started selling off the lots three days after Dodge surveyed them. The first went for $150.

By August 7, though Cheyenne was mostly a city of tents, a mass meeting in a local store chose a committee to write a city charter. On September 19 the first newspaper of the town, a triweekly tabloid called the Cheyenne Leader, was launched. By December the newspaper was advising its readers to carry guns at night for self-protection because of “frequent occurrences of garroting.” On October 13 of the next year, the editor asserted:

“Pistols are almost as numerous as men. It is no longer thought to be an affair of any importance to take the life of a fellow being.”

At this point Cheyenne resorted to vigilante justice to solve the problems endemic to the American frontier. In January 1868 three men were arrested for theft but released on bail. The next morning they were found tied together with a sign that read “$900 stole … $500 Recovered … Next case goes up a tree. Beware of Vigilance Committee.” The next day vigilantes caught and hanged three “ruffians.”

In the rural cattle areas, things were much worse. As Edward W. Smith, of Evanston, told the U.S. Public Land Commission in 1879, “Away from settlements the shotgun is the only law.” As the cattle spread, conflicts between ranchers and homesteaders grew, and the reaction of the cattlemen led to the Johnson County Range War.

On Tuesday, April 5, 1892, a special six-car train sped north from Cheyenne, carrying 25 Texas gunmen along with another 24 locals who had joined them.

The men had a “Dead List of seventy men” they intended to kill.

Might does not make right, and it certainly does not make for liberty.

We don’t have information about the homicide rate in Cheyenne in the 1890s, though data for the mining town of Benton, California, suggests that there it may have reached an incredible high of 24,000 per 100,000! More likely it was closer to 83 per 100,000, the rate during the California gold rush, or 100 per 100,000, the rate in Dodge City, Kansas, in the days of Wyatt Earp.

Things turned out quite differently in Wyoming. The anarchy, fear and violence were contained. Those Texans with the kill list were soon holed up at the TA Ranch surrounded by lawmen from the town of Buffalo who were tipped off about their arrival. After three days of siege, the cavalry came, ordered in by President Benjamin Harrison, and shackled all of the Texans and their collaborators. Today, Wyoming largely enjoys freedom from fear, violence and dominance. It has one of the lowest homicide rates in the United States, about 1.9 per 100,000.

Wyoming has a pretty good record when it comes to helping people break free from the cage of norms, too. Take the subjugation of women. Even during the worst of times, women in Wyoming did not face the same restrictions as those in Pashtun areas of Afghanistan and Pakistan or many parts of Africa. But as everywhere else in the world, women in the first half of the 19th century had very limited power and no say in public affairs, and had to put up with myriad constraints on their behavior, both because of their unequal status in marriage and because of the norms and customs of their societies. That started to change as women got the right to vote.

The first state to grant female suffrage was Wyoming in 1869, earning it the nickname the Equality State. This wasn’t because Wyoming’s customs and norms favored women compared to other parts of the world. Rather, the state’s Legislature granted them voting rights, partly to make it more attractive for women to move to this new state, partly to ensure that there would be enough voters to meet the population requirement for statehood, and partly because once African Americans began gaining full citizenship and voting rights, it seemed less acceptable to leave women out of this process. There are many reasons why the cage of norms often starts breaking down once a state capable of shackling the hoodlums and enforcing laws is in place.

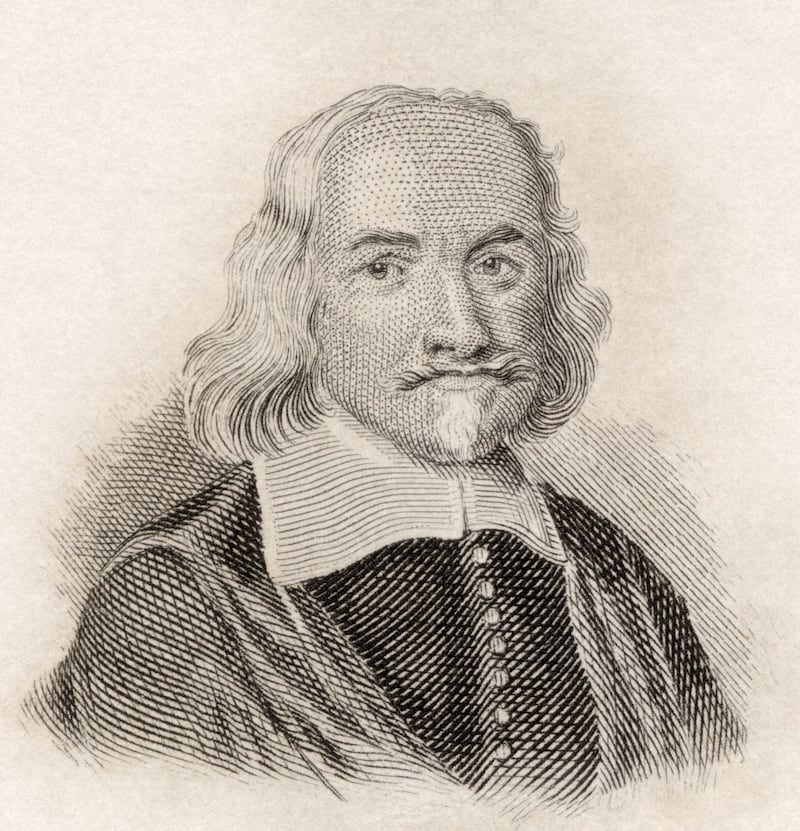

It’s not just murder that makes the lives of stateless societies precarious. Life expectancy at birth in stateless societies was very low, varying between 21 and 37 years. Similarly short lifespans and violent deaths were not unusual for our progenitors before the past 200 years. Thus many of our ancestors lived in what the famous political philosopher Thomas Hobbes described in his book “Leviathan” as “continuall feare, and danger of violent death; And the life of man, solitary, poore, nasty, brutish, and short.”

This was what Hobbes, writing during another nightmarish period, the English Civil War of the 1640s, described as a condition of “Warre,” or what Kaplan would have called “anarchy”— a situation of war of all against all, “of every man, against every man.”

Naturally, people would look for a way out of anarchy, a way to impose “restraint upon themselves” and get “themselves out from the miserable condition of ‘Warre,’ which is necessarily consequent … to the natural Passions of men.” Hobbes had already anticipated how this could happen when he introduced the notion of “Warre,” since he observed that “Warre” emerges when “men live without a common Power to keep them all in awe.” Hobbes dubbed this common Power the “great LEVIATHAN called a COMMON-WEALTH or STATE,” three words he used interchangeably. The solution to “Warre” was thus to create the sort of centralized authority that the members of anarchic, stateless societies did not have. Hobbes used the image of the leviathan, the great sea monster described in the Bible’s Book of Job, to stress that this state needed to be powerful. The frontispiece of his book featured an etching of the leviathan with a quotation from Job:

“There is no power on earth to be compared to him.” (Job 41:24)

Point taken.

Hobbes understood that the all-powerful leviathan would be feared. But better to fear one powerful leviathan than to fear everybody. The leviathan would stop the war of all against all, ensure people do not “endeavor to destroy, or subdue one another.”

Sounds great, but how exactly do you get a leviathan?

Hobbes proposed two routes. The first he called a “Common-wealth by Institution … when a Multitude of men do Agree, and Covenant, every one, with every one” to create such a state and delegate power and authority to it, or as he put it, “to submit their Wills, every one to his Will, and their Judgments, to his Judgment.” So a sort of grand social contract (“Covenant”) would accede to the creation of a leviathan. The second he called a “Common-wealth by Acquisition,” which “is acquired by force,” since Hobbes recognized that in a state of “Warre” somebody might emerge who would “subdueth his enemies to his will.” The important thing was that “the Rights, and Consequences of Sovereignty, are the same in both.” However society got a leviathan, Hobbes believed, the consequences would be the same — the end of “Warre.”

This conclusion might sound surprising, but Hobbes’s logic is revealed by his discussion of the three alternative ways to govern a state: through monarchy, aristocracy or democracy. Though these appear to be very different decision-making institutions, Hobbes argued that “the difference between these three kindes of Common-wealth consisteth not in the difference of Power; but in the difference of Convenience.” On balance, a monarchy was more likely to be convenient and had practical advantages, but the main point is that a leviathan, however governed, would do what a leviathan does. It would stop “Warre,” abolish “continuall feare” and seek to preserve “Peace and Justice.”

The influence of Hobbes’s masterpiece on modern social science can hardly be exaggerated. In theorizing about states and constitutions, we follow Hobbes and start with what problems states and constitutions solve, how they constrain behavior and how they reallocate power in society. But even more profound is his influence on how we perceive states today. We respect them and their representatives, regardless of whether they are monarchies, aristocracies or democracies. Even after a military coup or civil war, representatives of the new government, flying in their official jets, take their seats in the United Nations, and the international community looks to them to enforce laws, resolve conflicts and protect their citizens. It confers on them official respect. Just as Hobbes envisaged, whatever their origins and path to power, rulers epitomize the leviathan, and they have legitimacy.

Hobbes was right that avoiding “Warre” is a critical priority for humans. He was also correct in anticipating that once states formed and began monopolizing the means of violence and enforcing their laws, killings declined. The leviathan controlled the “Warre” of “every man, against every man.” Under Western and Northern European states, murder rates today are only 1 per 100,000 or less; public services are effective, efficient and plentiful; and people have come as close to liberty as at any time in human history.

But there was also much that Hobbes didn’t get right. For one, it turns out that stateless societies are quite capable of controlling violence and putting a lid on conflict, though as we’ll see this doesn’t bring much liberty. For another, he was too optimistic about the liberty that states would bring. Indeed, Hobbes was wrong on one defining issue (and so is the international community, we might add): Might does not make right, and it certainly does not make for liberty. Life under the yoke of the state can be nasty, brutish and short, too.

The leviathan that got the “Warre” under control and started to break the cage of norms in Wyoming is a different kind of beast from the ones we have discussed so far. It wasn’t absent except in the very early days. It had the capacity to shackle the Texans. Since then it has massively expanded this capacity and can now resolve myriad conflicts fairly, enforce a complex set of laws and provide public services that its citizens demand and enjoy. It has a large, effective bureaucracy (even if it is at times bloated and inefficient) and a huge amount of information about what its citizens are up to. It has the strongest military in the world. But it doesn’t use this military power and its information to repress and exploit its citizens (for the most part). It responds to its citizens’ wishes and needs, and it can also intervene to loosen the cage of norms for everybody, particularly for its most disadvantaged citizens. It is a state that creates liberty.

The cage of norms often starts breaking down once a state capable of enforcing laws is in place.

It is accountable to society not just because it is bound by the U.S. Constitution and by the Bill of Rights, which emphatically exalts the rights of the citizens, but more important because it is shackled by people who will complain, demonstrate and even rise up if it oversteps its bounds. Its presidents and legislators are elected, and they are often kicked out of office when the society they are ruling over doesn’t like what they are doing. Its bureaucrats are subject to review and oversight. It is powerful, but coexists with and listens to a society that is vigilant and willing to get involved in politics and contest power. It is what we’ll call a “shackled leviathan.” In the same way that the leviathan can shackle those Texan gunmen, so that they cannot do harm to ordinary citizens, it can itself be shackled by common people, by norms and by institutions — in short by society.

It is not that the “shackled leviathan” isn’t Janus-faced. It is, and repression and dominance are as much in its DNA as they are in the DNA of the “despotic leviathan.” But the shackles prevent it from rearing its fearsome face.

Liberty has been rare in human history. Many societies have not developed any centralized authority capable of enforcing laws, resolving conflicts peacefully and protecting the weak against the strong. Instead they have often imposed a cage of norms on people, with similarly dire consequences for liberty. Wherever the Leviathan has shown up, the lot of liberty has hardly improved. Even though it has enforced laws and kept the peace in some domains, the leviathan has often been despotic, thus unresponsive to society, and has done little to further the liberty of its citizens. Only shackled states have used their power to protect liberty. The “shackled leviathan” has been distinctive in another sense, too — in creating broad-based economic opportunities and incentives and promoting a sustained rise in economic prosperity. But this “shackled leviathan” has arrived on the scene only late in history, and its rise has been contested and contentious.

It isn’t that we are heading toward the end of history with the inexorable rise of liberty. It isn’t that anarchy will spread around the world uncontrollably. It isn’t even that all countries around the world will succumb to dictatorships, whether digital or just of the good old-fashioned sort. These are all possibilities, and this diversity, rather than convergence to one of these outcomes, is the norm. Nevertheless, there is also a glimmer of hope, because humans are capable of constructing a “shackled leviathan,” which can resolve conflicts, refrain from despotism and promote liberty by loosening the cage of norms. Indeed, a lot of human progress depends on societies’ ability to build such a state. But building and defending —and controlling — a “shackled leviathan” takes effort, and is always a work in progress, often fraught with danger and instability.

All in all, we are seeing a rather different picture from the one Hobbes painted. The problem in societies where the leviathan is absent isn’t just uncontrolled violence of “every man, against every man.” Equally critical is the cage of norms, which creates a rigid set of expectations and a panoply of unequal social relations producing a different but no lighter form of dominance.

Perhaps centralized, powerful states can help us achieve liberty? But we have seen that such states are likely to act despotically, repress their citizens and stamp out liberty rather than promote it.

Are we then doomed to choose between one type of dominance over another? Trapped in either “Warre” or the cage of norms or under the yoke of a despotic state? Though there is nothing automatic about the emergence of liberty, and it hasn’t been easy to achieve in human history, there is room for liberty in human affairs and this critically depends on the emergence of states and state institutions. Yet these must be very different from what Hobbes imagined — not the all-powerful, unrestrained sea monster, but a shackled state. We need a state that has the capacity to enforce laws, control violence, resolve conflicts and provide public services but is still tamed and controlled by an assertive, well-organized society.

Excerpted from Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson’s “The Narrow Corridor,” published by Penguin Random House. Daron Acemoglu is the Elizabeth and James Killian Professor of Economics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology . James A. Robinson is a political scientist, economist and a University Professor at the University of Chicago.

This story appears in the July/August issue of Deseret Magazine. Learn more about how to subscribe.