A block or two from the final resting places of music legends like Sammy Davis Jr. and Michael Jackson, tucked into a quiet suburban neighborhood north of Los Angeles’ boutique donut shops and designer denim retailers, you might hear the muffled three-fingered rolls of a banjo resounding off the stucco walls of adjacent houses.

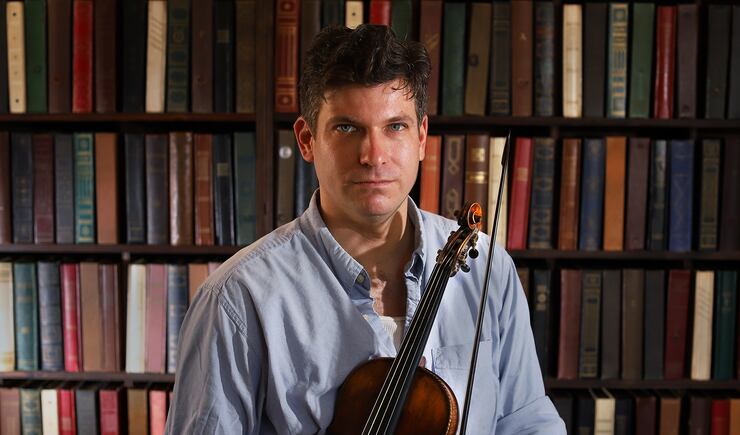

I’m on Frank Fairfield’s street, a California multi-instrumentalist who draws influences from his vast knowledge of Anglo American folk music and a unique childhood spent at a Mennonite seminary in Central America. In years past, he could be found busking on the streets of L.A., playing music for passersby on boardwalks and outside bookstores. You could also find him performing at the Kennedy Center, behind NPR’s Tiny Desk, or touring with the popular indie band Fleet Foxes.

But after 2015, he became a ghost; he had “quit the music racket,” to the dismay of his fans. I visited Frank to ask why. He agreed to give me a banjo lesson, so I met him at his house to understand how someone who was succeeding in a cutthroat industry would walk away when fame is so often regarded as the pinnacle of success. I learned that public attention has a dark side and that it takes courage to walk away.

I wander through Frank’s home, over the wooden floorboards and through a back door. He leads me under a shady pagoda to a space resembling something between a shed and a backyard barn. With the door open I can make out two chairs carefully placed to face one another, on a well-worn rug, under the exposed beams and lights.

This is where Frank practices for hours a day. It struck me that I had not seen a television or computer screen in my visit so far.

Frank is standing in his barn, flushed in the midday heat, and wiping his face with a handkerchief from his back pocket. He hands me a banjo, with mellow nylon strings and an imitation animal hide head.

It feels like we are engaging in an old tradition.

Fairfield was born in Fresno, California, and he can’t remember a time when he didn’t know how to play an instrument. When he was 7 years old, his father got a job at a Mennonite seminary and moved the family to Guatemala City. Much of his early playing was music learned in church.

Many musicians start in a house of worship. Spiritual songs have emotional power and an accessible community of music makers to provide a cradle for learning. Frank believes a love of music should drive practice, not the other way around.

“Obviously, we have to work on the actual practice of getting our hands to do what we want them to do,” he says, “and we might have to learn enough of the theory for your fingers to know where to go, but at the end of the day — why are we doing this? What’s the point of it?”

I’ve taken many music lessons in my life, but none have started with the “why” behind the playing. And “the point” of Frank’s music surprises me. He cites the writings of Austrian composer Arnold Schoenberg to illustrate that “All the other things that humans do; they write literature, and they paint, it’s all a representation of something else. While music can be itself.”

“It’s just music.” he muses, “It doesn’t have to be tied to anything, it doesn’t have to mean anything. It’s just human phrase and expression.”

He plunges into a song called “Spirit of the Morning,” and brings it to life with animation. He describes musical phrases as voices, and nimbly joins them together in a conversation — one I had never heard before. And this was his point about music, he says, it’s human emotion purely communicated.

Frank’s family returned from Central America when he was 16, and put down roots in Pasadena. And maybe because his most formative years were spent abroad, there remains something unfamiliar about him.

Frank has a way of speaking that recalls the radio age, his cadence and word choice suggesting an English slightly removed from our time. His clothing is likely informed by his upbringing in the Mennonite church; it’s simple and functional with no branding.

From my perspective, Frank very intentionally cultivates an environment that reduces the noise and clutter of contemporary life. His house, his shed and his clothes all seem carefully selected to build a reality you can touch and feel and understand. They are not representations. They are the things themselves, unfiltered by digital distraction.

We sat in the quiet of his barn, and he spoke about what really convinced him to “put the work in,” practicing scales for hours a day. The secret is falling in love with a repertoire. “You can’t put the instrument down because you want to get closer to it. You want to abide in this. You want to taste it and be in communion with it more deeply.”

When Frank talks about music, he is describing a quasi-spiritual experience.

We start in on a classic banjo tune, “Cumberland Gap.” Frank learned the version he plays from a rare vinyl in his vast collection, one of the first-ever recordings of a folk song on solo banjo with vocal in the 1920s by Land Norris.

Frank tells me that we, as music makers, should submit to the pain of practice in order to “learn about movement and about how our thoughts and intentions become actions.” We ask ourselves “Where is the issue? Is it in the intention or the manifestation of the intention?” In this way, practicing is about constantly taking ourselves apart to be put back together again, so our life is filled with a series of tiny but meaningful adjustments.

This approach was likely developed as Frank played on the streets to support himself. Every day he was performing and practicing at the same time. He had to rely on his art to live and was that much more attentive to the ways his music was communicated to real people. Like a stand-up comedian listening for laughs, he was able to dissect his playing and evaluate it based on the reactions of people who either stopped to listen or shuffled onward.

“It’s not just some predetermined thing, that we’re just watching the world go by.” Vibrant music is created by artists who believe in their own agency. But though the musician is producing the sound, Fairfield said, “you realize the world is making decisions, and the music is making choices. It feels like it is created right in front of you.”

After the lesson, I hung around in Frank’s minimalist kitchen while he fiddled with his ceramic French press. I was eager to learn more about his life as a touring musician, though he was hesitant to unpack the past. He seemed to think there were far more interesting things to talk about but reluctantly shared what led to his exit from public life.

After moving around, and working jobs as a manual laborer, Frank started getting serious about his music. He began playing anywhere there might be an attentive audience. It was at a farmers market in Hollywood where Matt Popieluch, a seasoned singer-songwriter from the band Foreign Born saw him playing.

Acting as Frank’s manager, Popieluch facilitated shows and brought him to Josh Rosenthal’s record label, Thomkins Square. With his old-world style, Frank made it easy for marketing professionals to neatly package him up for sale.

He told me “they wanted a story or some sort of myth or something. It wasn’t really about the music. They wanted an aura. It was a lot of pressure to put on yourself.” And claiming he was not a big enough personality to handle that pressure, he began to feel like a caricature of himself.

Though there were many aspects of performing he enjoyed, he said “It kind of felt like my job was to hate myself every night. I used to hate myself in a different town every night. That was mostly what it felt like.” He was forced to focus on crowd-pleasing and felt insincere as a performer.

The struggle to separate who he was from who people wanted him to be, finally came to a head with his decision to walk away from touring. “I feel like since moving away from that, going back to doing construction work and carpentry, it helped settle me down to wanting to actually study music as a serious thing.”

After touring, Frank could still be heard in surprising places, though.

He covered Orville Reed’s “The Telephone Girl” for the soundtrack to the 2012 film “Lawless,” starring Tom Hardy and Shia LeBoeuf. He performed Charlie Poole’s “If the River Was Whiskey” for the American Epic Sessions. He even voiced an animated character on the show “Over the Garden Wall.” But he has been largely out of the spotlight in recent years, performing only when he wants to, with who he wants to.

He told me about his current work, keeping the Bob Baker Marionette Theater alive. Frank helps build sets and intricate puppets for the official Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument, apparently loved by celebrities like “Get Out” director Jordan Peele and generations of families.

There seems to be a new-found purity in Frank’s pursuits, as he follows diverging threads of curiosity for his own edification and enjoyment.

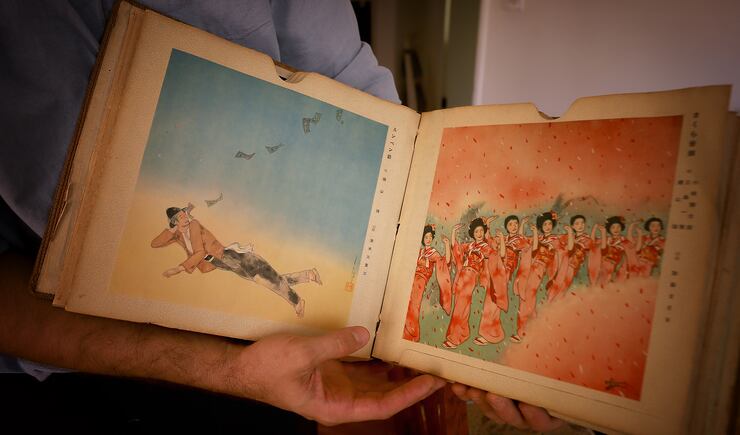

Frank walks me to a back room, where shoulder-high cabinets are packed with what appeared to be old photo albums. Instead of photos, every volume contained tattered paper sleeves with 78s inside, a type of record that hasn’t been produced since the late ’50s.

He thumbed through a section, showing me the rare record containing “Cumberland Gap,” from the lesson. Then, he deftly extracted a recording of Arnold Dolmetsch, playing baroque music with his daughters. Fairfield loves it because “It’s not too precious, not overly embellished or sentimental.”

“It’s exciting to feel a new tug at your heart from a direction you’ve never felt before,” he said. This is what he has now dedicated his life to pursuing, through the teaching of his art and small performances with kindred musicians. “Music is a pretty good reflection of our value systems. What you invest in is what grows.”

Frank waves off most questions about his potential fame as inconsequential when compared to the more profound investigation he is a part of. Learning about ourselves by studying Mattisse, Thomas Morley or Pandolfi. He believes every discipline should be a way to look into ourselves, or else the point is lost. “There are profound things to learn about ourselves from any study, any discipline. Everything should be profound or else what’s the point? What are we doing?”

Frank might have cracked the code, moving beyond the pursuit of fame to something more permanent — human nature, the divine connection we share with each other and the lessons of the past.

It was difficult not to see the irony in his self-effacing attitude, as he stood surrounded by countless historical records — the fruits of his deep musical explorations. “I’m by no means some authority on these songs,” Frank said. “I just sing them sometimes.”