Hundreds of edits have been made to new editions of Roald Dahl’s children’s books to make them more inclusive, sparking outrage and causing many authors to speak out against what some are referring to as censorship.

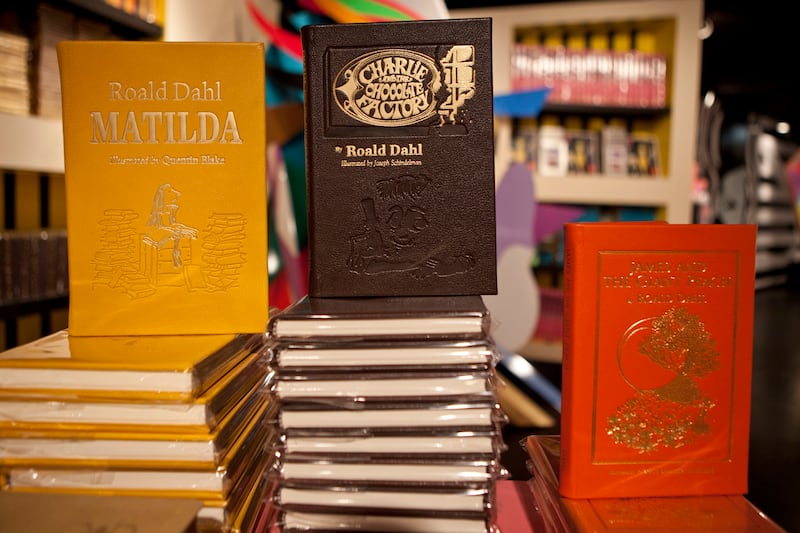

At least 10 of Dahl’s classic children’s books, including “Charlie and the Chocolate Factory,” “Matilda” and “James and the Giant Peach” were edited to make them less offensive to readers. Passages that referred to weight, gender, race, violence, mental health and more were altered, with some being removed altogether.

Why did the publishers edit Roald Dahl’s books?

A note about the changes was added to copyright page of the Puffin Book’s latest editions of Dahl’s children books, the Daily Telegraph first reported.

“Words matter. The wonderful words of Roald Dahl can transport you to different worlds and introduce you to the most marvellous characters. This book was written many years ago, and so we regularly review the language to ensure that it can continue to be enjoyed by all today,” reads the edition notice.

The changes were made by Puffin Books and the Roald Dahl Story Company, with the help of Inclusive Minds — a “collective which is working to make children’s literature more inclusive and accessible,” according to The Associated Press.

A spokesperson for the Roald Dahl Story Company explained why the changes were made in a statement emailed to The Washington Post, saying the company wanted “to ensure that Roald Dahl’s wonderful stories and characters continue to be enjoyed by all children today.”

“When publishing new print runs of books written years ago, it’s not unusual to review the language used alongside updating other details including a book’s cover and page layout,” the statement read.

What changes have been made to Roald Dahl’s books?

The Telegraph found “hundreds of changes” made to at least 10 of Dahl’s children’s books.

For example, in “Charlie and the Chocolate Factory,” the term “fat” is no longer used to describe the character Augustus Gloop, “mothers and fathers” is now “parents,” and the Oompa-Loompas were changed from “tiny men” to “little people.”

Meanwhile, in “Matilda,” references to Joseph Conrad and Rudyard Kipling were replaced with Jane Austen and John Steinbeck.

In “The Twits” a “weird African language” removed the word “weird,” and in “James and the Giant Peach,” Miss Spider’s head is no longer described as “black.”

See the Telegraph for a full list of the changes they found.

How have authors reacted to the changes to Roald Dahl’s books?

Many authors were upset about the posthumous changes to Dahl’s books, with renowned author Salman Rushdie, known for his controversial book “The Satanic Verses,” calling the edits “absurd censorship.”

“Roald Dahl was no angel but this is absurd censorship. Puffin Books and the Dahl estate should be ashamed,” Rushdie tweeted.

Cristopher Paolini, known for his fantasy book “Eragon,” tweeted, “This is wrong. Ban a book if you must. Or put a content warning at the front. But don’t rewrite it. Don’t put words in an author’s mouth (especially one who has no say in the matter).”

In a follow-up tweet, Paolini clarified that he was not in favor of banning books, clarifying that he meant “altering the words of an unconsenting party (that is, a dead author), is actually WORSE than banning.”

Author Philip Pullman, known for “His Dark Materials,” told BBC Radio 4’s “Today” program that he believed Dahl’s books should go out of print rather than be edited and republished.

“Let him go out of print,” Pullman said per The Independent. “Read all of these wonderful authors who are writing today, who don’t get as much of a look-in because of the massive commercial gravity of people like Roald Dahl.”

“What are you going to do about them? All these words are still there, are you going to round up all the books and cross them out with a big black pen?” Pullman asked.