In April 1890, John Wesley Powell stood before a room full of U.S. senators to deliver a message as timeless as the landscapes he mapped.

The 56-year-old director of the U.S. Geological Survey was a military man who had lived a life of adventure unlikely experienced by his audience of well-heeled politicians. The son of English immigrants and a Union Army lieutenant in the Civil War, Powell was the first white man to lead an expedition down the Colorado River. A rugged explorer and the last of an iconic generation of frontiersmen, he sported an unkempt beard that covered his weathered face and was often dotted with ash from his cigars. His right arm was reduced to a stump by a Confederate bullet. He stood only five feet, six inches tall, but commanded the room, speaking slowly and thoughtfully with each word carrying more weight than the last.

Powell was nearing the end of his life, and in his final decade, starting on that spring day in Washington, D.C., he became a counterweight to the prevailing narrative at the time.

The West, he warned, could not sustain the country’s grandiose plans of development and expansion.

“It would be almost a criminal act to go on as we are doing now, and allow thousands and hundreds of thousands of people to establish homes where they cannot maintain themselves,” he told the senators. They were infuriated, and for more than a century after, the federal government ignored his warning.

Now, Powell’s prophecy is coming to pass. The West has been subjected to decades of drought, or depending on who you ask, aridification. The Colorado River, which feeds life to 40 million people and billion-dollar industries, has been reduced to a fraction of its former self. Utah’s Great Salt Lake is shrinking, with large clouds of toxic dust billowing across Salt Lake City in the summer. Wildfires, accelerated by invasive beetles that turn entire forests brown, fill the region with smoke.

All the while, the Mountain West, or the region we at the magazine think of as Deseret, is buckling under explosive growth in places like Bozeman, Boise and Boulder.

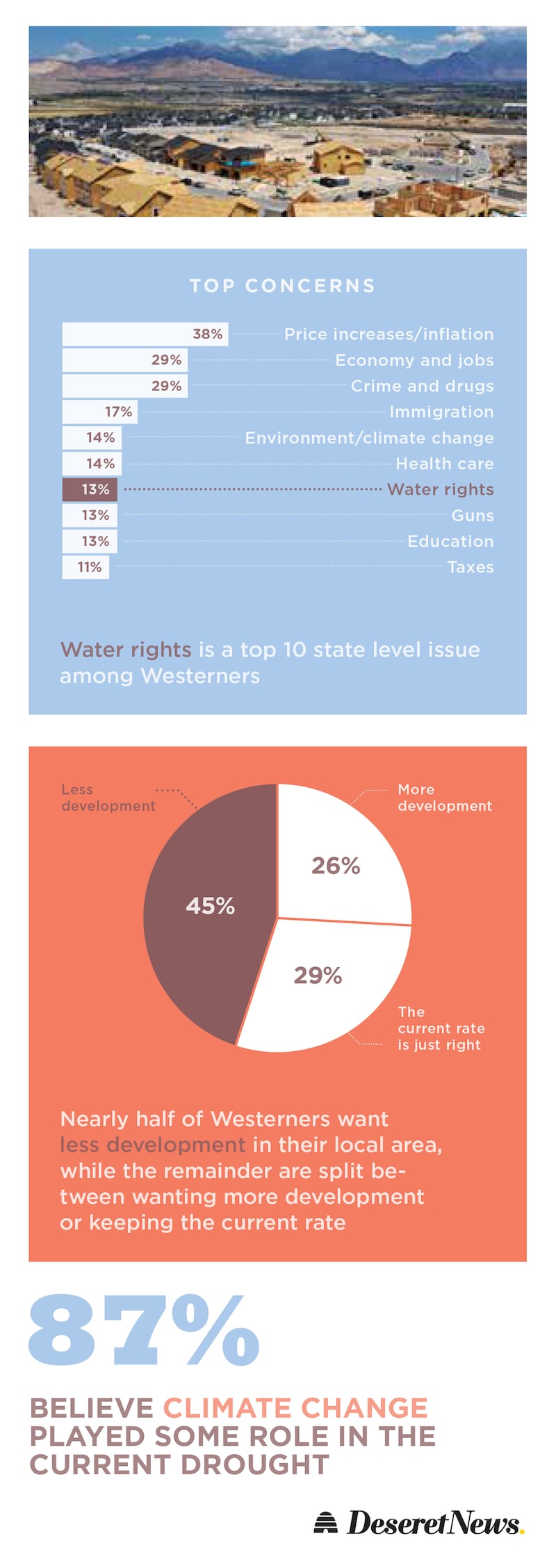

And that is causing a generational sea change in public opinion. For decades, policymakers and business leaders have pushed a no-brakes growth mentality, but according to a new poll conducted by the national polling firm HarrisX and Deseret Magazine, residents are beginning to question that approach and what it has wrought.

“The basic philosophy of westward expansion has been, ‘Look, there’s an unspoiled area – let’s go spoil it,’” says Dan McCool, an author and professor emeritus at the University of Utah who researches public land policy and water resource development. “It’s uncrowded — so let’s make it crowded. It’s clean — well, let’s go make it dirty. There’s no traffic — let’s increase the traffic.”

According to the poll, which surveyed 1,764 adults in Arizona, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, Wyoming and eastern Oregon and Washington, only one-third of respondents say they approve of how their elected officials are managing population growth, while half disapprove. And about 60 percent think their state’s economic trends are harming residents — a sentiment held by 69 percent of rural respondents.

“The basic philosophy of westward expansion has been, ‘look, there’s an unspoiled area — let’s go spoil it. It’s uncrowded — so let’s make it crowded.” — Dan McCool, University of Utah

In Utah, nearly half of respondents have considered moving to a different state because of housing prices, and across the region, the majority say their state is growing too quickly.

Encouraging growth and expansion, which in turn strain resources, are an affront to what Aaron Weiss calls the “Western way of life.”

“It’s different from life on the California coast or the East Coast, or Florida. And holding on to that Western way of life, that Western identity, is really important to people,” says Weiss, the deputy director of the Center for Western Priorities based in Denver. And growth is only one half of a double-threat. “Folks are suddenly recognizing that climate change is in fact, an existential threat to the Western way of life,” Weiss adds.

Still, politicians of all stripes see the region’s growing population and economy as a byproduct of good policy and foresight. When Utah Republican Gov. Spencer Cox was recently asked if his state is too developer friendly, he pushed back. “We need development,” he said. “Like, there is no other way.”

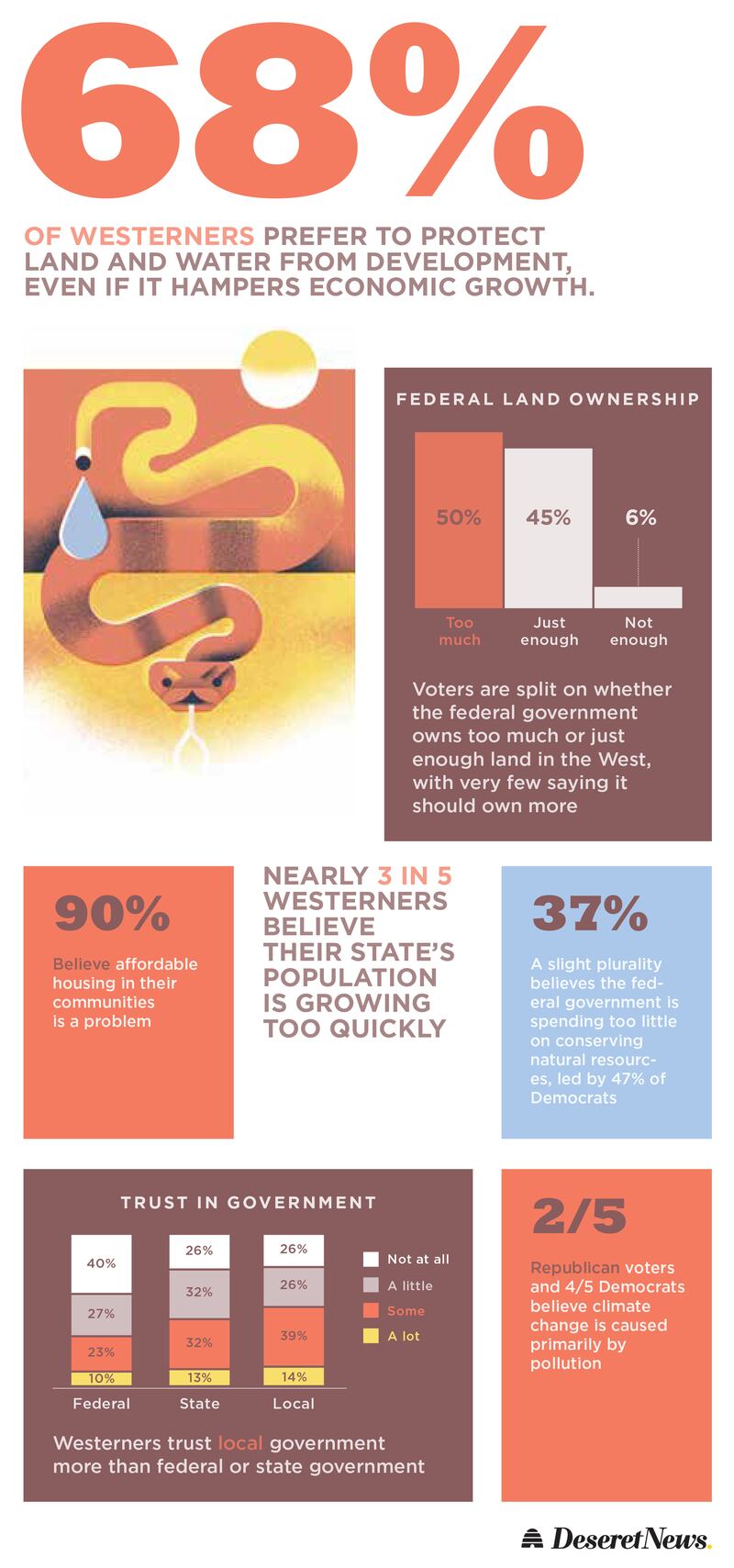

But the Deseret Magazine survey identifies a disconnect between policymakers and voters. It found 68 percent of Westerners say they prefer to protect land and water from development, even if that hampers economic growth.

“It’s still basically the political third rail to say growth is not good,” says McCool. Even if that growth is completely at odds with issues like water conservation, which according to the poll, is increasingly top of mind.

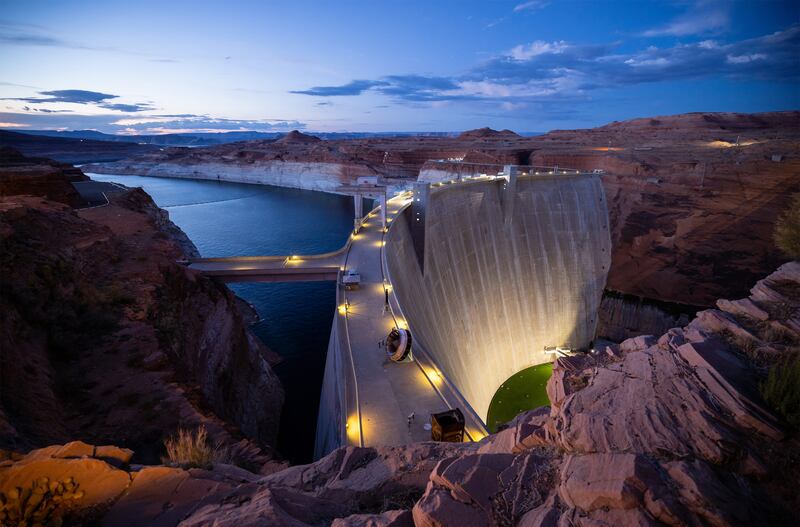

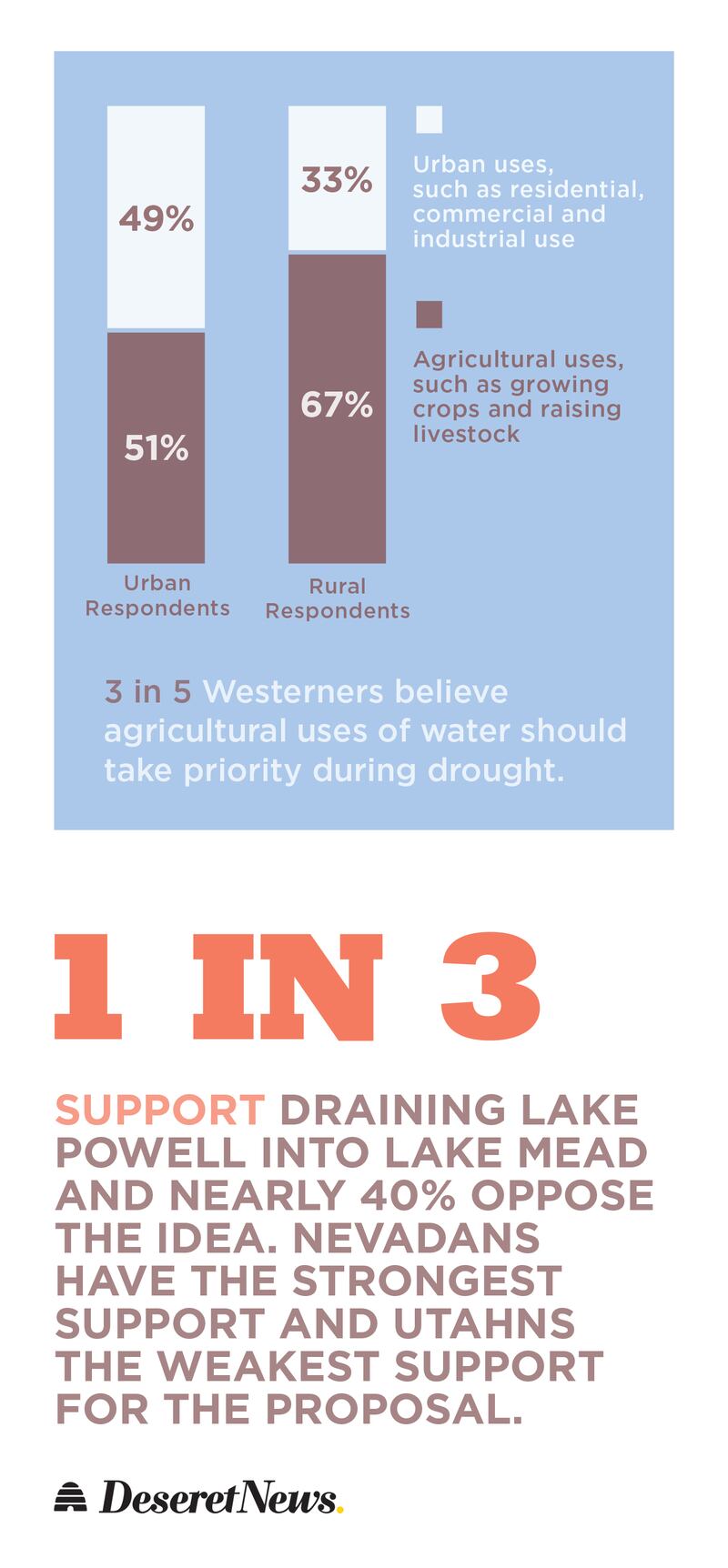

About 80 percent of respondents say water supply is of primary concern, a sentiment heightened in arid states like Utah and Arizona. Roughly the same percentage of people surveyed think access to water will continue to be an issue in 2030. Over 30 percent say Lake Powell — the nation’s second largest reservoir created by a dam along the Colorado River — should be drained. About 40 percent oppose the idea, and 30 percent aren’t sure.

“That shows that folks are very aware that climate change and drought are huge problems in the West,” Weiss says, “and there’s obviously an awareness of that across parties, across demographic groups, across urban and rural areas.”

It’s hard to ignore the drought when you turn on your faucet and no water comes out, which happened to residents near Scottsdale, Arizona, in January; or when a dire forecast warns that the Great Salt Lake could vanish in five years, according to a recent report; or when 500 homes are destroyed and 30,000 people are evacuated during an unprecedented December wildfire in Colorado.

So, how should policymakers respond? In a free-market economy, government is reluctant to put the brakes on growth, as McCool points out, “but we could certainly stop subsidizing it.”

“If a company wants to come here and says ‘we need a million gallons of water,’ the response should be ‘you’re going to have to pay to conserve a million gallons of water someplace else,” he says.

That message could have come from Powell himself. Given his hard line at the time, one wonders if the legendary explorer would have been surprised that the West’s unfettered growth has continued to this point without utter destruction. Powell’s warnings drew the ire of Congress, who after his testimony in 1890 slashed funding for his work and continued to promote new settlements in the West.

Powell was disheartened, but persisted. In 1893, he spoke at a conference in Los Angeles, with a perspective that remains timeless.

“There is not enough water to irrigate all the lands,” he said. “It is not right to speak about the area of the public domain in terms of acres that extend over the land, but in terms of acres that can be supplied with water.”

This story appears in the March issue of Deseret Magazine. Learn more about how to subscribe.