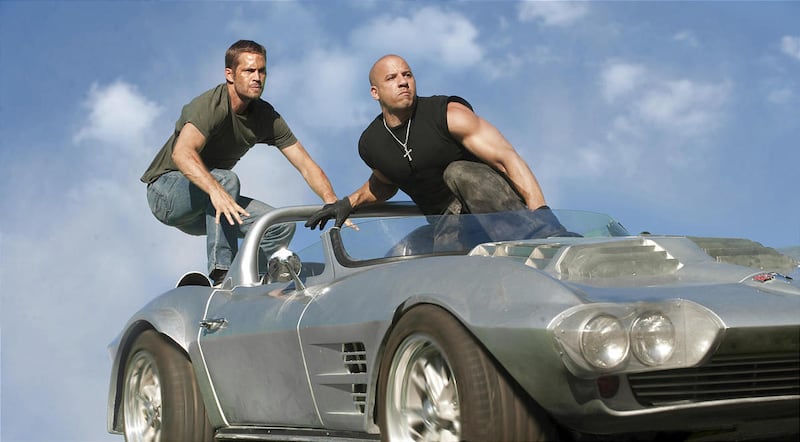

About a week ago, I was shocked to see the late Paul Walker in a trailer for “Fast X” — the 12th movie in the “Fast and Furious” franchise. I had naively assumed the franchise wrote Walker’s character off the series after his death in 2013. But this isn’t even the first “Fast and Furious” movie Walker’s been resurrected for. In 2013, the franchise used CGI to complete Walker’s scenes in “Fast and Furious 7” after his untimely death.

The same was done for Carrie Fisher in “The Rise of Skywalker.” Audrey Hepburn got virtually resurrected for a Galaxy advertisement. “Game of Death” brought Bruce Lee back to life. Oliver Reed, Peter Cushing, Philip Seymour Hoffman and Brandon Lee have also made posthumous returns to the big screen.

CGI resurrections aren’t necessarily commonplace, but it’s a practice that has faced a fair share of controversy. And it raises several question, such as: How do they do it? Who gives movie-makers permission to resurrect actors? And what does it mean for the future of movies?

A brief history of resurrecting actors in movies

Before CGI, late actors were resurrected in movies using practical methods such as body doubles, masks and limited screen time.

Amid filming for “Game of Death,” Lee was killed by a brain swell from hyponatremia, or having a low concentration of sodium in the bloodstream, per the New York Post. To complete the second half of the movie, Lee’s scenes were cut down and filled using stand-ins wearing beards and masks to hide their faces. Cardboard cutouts of Lee were even used in some scenes, reports Yahoo News.

Nowadays, advancements in CGI has allowed movie-makers to bring an actor’s likeness back with impressive results. But it’s still a complicated business — bringing Fisher back to the “Star Wars” franchise was a “massive kind of problem” and a “gigantic puzzle,” according to the movie’s visual effects supervisor, Roger Guyett, per Insider.

How are actors resurrected with CGI?

It’s complex. “Rogue One” filmmakers explained their experience with the process to The New York Times after using CGI to resurrect Cushing as the “Star Wars” character Grand Moff Tarkin.

Filmmakers cast Guy Henry for principal photography — the 6-foot-4 actor has a similar build and stature as the late Cushing. Throughout filming, Henry wore motion-capture materials on his head so his face could be digitally replaced with Cushing’s image.

“We’re transforming the actor’s appearance to look like another character, but just using digital technology,” said John Knoll, the chief creative officer at Industrial Light & Magic and a visual effects supervisor on “Rogue One,” per The New York Times.

It’s difficult to perfectly match a late actor’s likeness. Nuances such as how they open their mouth or move their eyebrows might be different from the stand-in actor. When in doubt, filmmakers prioritized realism over likeness.

“It is extremely labor-intensive and expensive to do. I don’t imagine anybody engaging in this kind of thing in a casual manner,” Knoll added.

Who gives filmmakers permission to resurrect public figures?

Again, it’s complicated. It depends on who holds the late actor’s rights.

The right of publicity became California state law in 1985. The law states that the rights to a celebrity’s image — including voice and likeness — are transferred to the celebrity’s estate after they die. Any money from licensing the image also goes to the estate. And if a filmmaker wants to use an actor’s image, they require permission from the estate, per Wired.

Right of publicity laws vary in each U.S. state. Some states provide post-mortem protection, which means a public figure’s image is exempt from use in certain media, such as motion pictures, songs, plays and novels.

Post-mortem protection lasts for a different length of time in each state. “In California’s case, the limit is 70 years after the death of the person in question. In Illinois, that term is 50 years after the person’s death,” David A. Simon told Wired, a visiting assistant professor at the University of Kansas and a fellow at the Hanken School of Economics. “The differences are numerous between states.”

But once the right of publicity sentence passes, the figure’s image is fair game. James Dean, for example, died in 1955 and is coming up on the end of his 70-year protection, which could potentially make his image free to anyone.

“If they still have an identity that is being commercialised, such as their estate selling products and services associated with them, then that person’s identity could continue to be protected under US trademark and unfair competition law,” Jennifer Rothman, professor of law at Loyola Marymount University, told Wired.

Worldwide XR’s catalogue of celebrities

A few years ago, intellectual property licensing specialist CMG Worldwide joined forces with content creation studio Observe Media to form Worldwide XR.

Worldwide XR represents more than 400 actors, athletes, musicians, artists and historical icons, such as Dean, Rosa Parks, Lou Gehrig, Andre the Giant, Malcolm X, Maya Angelou and Chuck Berry.

CMG Worldwide was started by Mark Roesler in 1982 after finding that there was no one to represent the estates of dead stars. Families of celebrities began approaching CMG for representation. The company’s first two clients were Elvis Presley and Dean, per Wired.

“Once you successfully represent one dead celebrity, other estates will look to that company that did well with someone else,” Rothman told Wired.

Public pushback over CGI resurrection

In 2019, film directors Anton Ernst and Tati Golykh announced that Dean would star in “Finding Jack” — the Vietnam War action drama would resurrect Dean through CGI, per The Hollywood Reporter.

The public wasn’t happy about it.

“This is awful,” Chris Evans criticized on Twitter. “Maybe we can get a computer to paint us a new Picasso. Or write a couple new John Lennon tunes.”

Elijah Wood also slammed the use of Dean. “NOPE. this shouldn’t be a thing,” Wood tweeted.

“Finding Jack” never made it to theaters.

“If we aren’t doing anything to hurt James Dean’s image, why are people pushing back?” asked Ernst, per The New York Times. “I’m trying to analyze what the moral issue is here.”

One “moral issue” linked to CGI resurrection is the ability to exploit dead actors by casting them in roles they could not select for themselves.

“Acting is about making a choice to take on a role, and is not a choice that should be make for anyone,” Zac Thompson wrote in HuffPost after Cushing was revived for “Rogue One.”

“I mean, we already have problems with leaking celebrities’ nude selfies, so how far off are we from mapping their likeness onto pornographic scenes? It’s unprecedented territory, a whole new world of morality and consent that needs be addressed,” continued Thompson.

Once the floodgates are opened, several concerns arise. Who has access to this technology? Where is the line drawn? What type of roles take this too far? And will CGI eventually replace real-life actors?