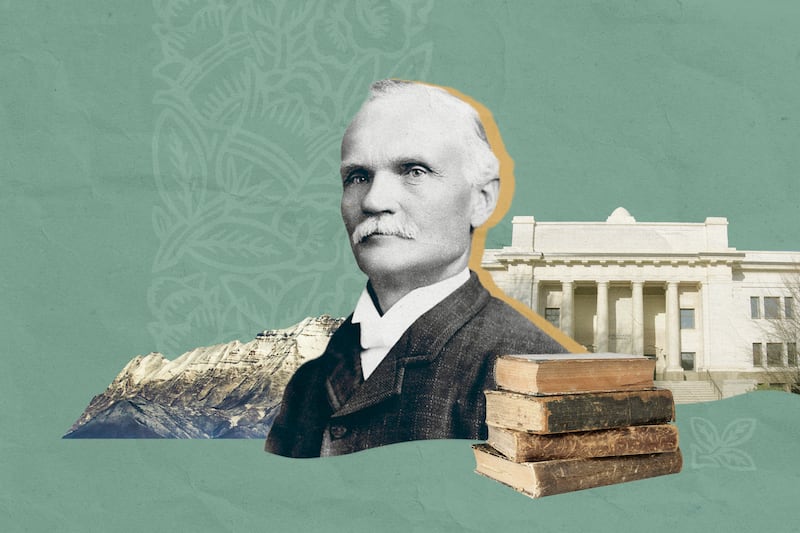

A German immigrant and Latter-day Saint pioneer of humble beginnings, Karl G. Maeser has often been referred to as the “spiritual architect” of Brigham Young University.

Yet also of humble character, and it being many years since he lived, Maeser’s story has quietly become lost to many of the approximately 35,000 students that enroll in the university each year.

How do I know this? Because I was one of them.

Or at least I was until a group of my fellow journalism students and I set off to begin an intense process of research, prayer and preparation to tell the story of Karl G. Maeser — a man whose faith, education and service directly shaped and continue to guide the university even now, 150 years after its founding on Oct. 16, 1875.

“Karl G. Maeser was certainly one of the most refined and educated men to join (The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints) in the first 50 years of its restored existence,” said the late-President Jeffrey R. Holland of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, addressing the BYU campus community as university president in September 1987.

For months earlier last year, my fellow classmates and I dove deep into any and all books, biographies and archival resources that made mention of this “most refined and educated” man. We conducted an at least 2-hour interview with A. LeGrand Richards, a former religion professor at BYU and author of Maeser’s biography, “Called to Teach.” And for about a week in February, we traced the start of Maeser’s story in Germany, logging at least 20 hours of footage, capturing approximately 2,300 photographs and conducting more than two dozen interviews.

All for what? Surely all of the mental, physical and academic stretching our work required culminated in a capstone documentary project that was later combined with a second group’s research of Maeser’s time in London.

Yet beyond that, our work and final documentary project became a spiritually defining journey, one that I consider the capstone of my BYU education.

Learning from Maeser: A principal of potential

William Shakespeare’s “Twelfth Night” includes the popular phrase, which says, “Some are born great, some achieve greatness, and some have greatness thrust upon them.”

Yet Maeser, having been transformed by both his secular and spiritual education, believed that every person — each a child of God — has a divine potential, and that it just needs to be drawn out of them.

This belief was evident in the way he — a school teacher and second principal of Brigham Young Academy, BYU’s precursor — taught. For instance, Maeser once told teachers there are two kinds of children they would encounter.

The first, he said, “grows up in an atmosphere of love, tenderness, where kind words, gentle and tender care and loving hands are always seen and heard.” Meanwhile a second kind, he said, is “starving for love, for a kind word, a loving expression.”

These, he continued, “are like the flowers that grow up in the cellar, where the rays of sunlight never smile on them. … These starving children are the ones that need our care, our love, our devotion.”

Through their expressed love and confidence, Maeser believed that both parents and teachers could unlock their young ones’ potential. “No coercion, manipulation, flattery, or bribery could move a student as powerfully,” wrote Richards, Maeser’s biographer.

Still, Maeser’s belief in one’s divine potential was not only evident in his teaching philosophy, but rather his entire life was a testament to it.

Born the son of a porcelain painter in the little town of Meissen, Germany, Maeser had limited access to education. He belonged to a lower social class, and seeing that the German educational system at the time was highly stratified, favoring the elite, Maeser’s chances of obtaining a quality education were slim.

Even still, a sudden and unusual change in the admissions policy of the nearby Kreuzschule Gymnasium — a prestigious preparatory school in Dresden, Germany — broadened the scope just enough to where Maeser was able to attend.

At that school, Maeser enrolled in a rigorous, classical education, with a heavy emphasis on Latin and Greek — common in any traditional gymnasium. Yet finding himself quickly disillusioned by the school’s elitism, Maeser decided to drop out two years in, and instead pursue his education at the Friedrichstadt Teacher College in Dresden.

Maeser’s “decision to become a teacher, which would eliminate his potential to improve his social status, might seem surprising,” Richards wrote in Maeser’s biography. “But Karl was not in school for social status.”

Instead, he was in it to do good, to become more. And become more he did.

Maeser: A man magnified ‘by study and also by faith’

Having chosen the more humble of his two educational routes, Maeser became immersed in practical training to become a school teacher.

His days at the teacher college ran from 5 a.m. to 10 p.m. and included practical teaching, as well as a deep study of religion, the Bible, German, orthography, composition, history, geography, natural science, arithmetic, drawing, public speaking and more.

Yet beyond this practical training, and perhaps most transformative, were the philosophical foundations Maeser was instructed in at the Friedrichstadt Teacher College.

For instance, it was at the teacher college that Maeser became well versed in the educational philosophies of Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi — a Swiss educational reformer who emphasized the goodness of human nature, individual potential and love rather than fear as motivation.

Pestalozzi’s ideas were “revolutionary,” Richards wrote, and based upon “a fundamental belief in the goodness of people and the potential of each individual to develop through his or her own choices and self-activity.”

Their “highest objective,” Richards continued, “sought to empower the child to become the chief agent of his own development.”

Also at the teacher college, Maeser was taught how to integrate faith into education, being warned against treating religion as merely another academic subject.

These and other educational philosophies would prove useful for Maeser in the years following his graduation in 1848. But it wasn’t until Maeser discovered and was baptized a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints that his life and career sprung into action.

This shift took place in 1855. When working as a teacher in Dresden, Germany, Maeser stumbled upon a pamphlet that ridiculed the teachings of the Church of Jesus Christ.

Reading the pamphlet through, Maeser felt the spirit of it was wrong, and thus decided he would need to inquire more. So, there being no missionaries allowed in Germany at the time, Maeser wrote a letter to the mission home in Denmark. This letter sparked a flurry of correspondence between him and the church’s missionaries in both Denmark and London.

And what ultimately resulted was Maeser’s baptism on Oct. 14, 1855.

Yet, his new faith came at a significant cost. The limited religious freedom at the time made it so his conversion put his career in jeopardy, threatening to undo everything he’d worked for. And yet that same conversion, and Maeser’s newfound commitment to the gospel of Jesus Christ, would soon prove to be the catalyst that would lead him to build an enduring legacy as a man dedicated to learning and teaching “by study and also by faith.”

“For me,” said Richards when interviewed for my team’s documentary on Maeser, “what you see is a man who’s got an independent spirit, who is willing to do what the Lord wants him to do. And he does that his whole life.”

Maeser: A man ‘prepared in all things’

In reflecting on what I learned from Maeser’s life and legacy, I was immediately drawn to an experience I had just months after completing my full-time missionary service for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

In January 2023, just days away from resuming my education at BYU, I sat in my dorm room at Heritage Halls feeling uneasy about what my future held. In an effort to bring peace to what my education would include, I decided to turn to the scriptures.

“Teach ye diligently and my grace shall attend you,” the scriptures read, “that you may be instructed more perfectly in theory, in principle, in doctrine, in the law of the gospel, in all things that pertain unto the kingdom of God, that are expedient for you to understand;

And that you may be instructed, it continued, “Of things both in heaven and in the earth, and under the earth; things which have been, things which are, things which must shortly come to pass; things which are at home, things which are abroad; the wars and the perplexities of the nations, and the judgments which are on the land; and a knowledge also of countries and of kingdoms.”

With every word I read, my uneasy mind began to feel a sense of mission, a mission to educate myself on things of both spiritual and secular value. But then the verse that followed added purpose.

“That ye may be prepared in all things when I shall send you again to magnify the calling whereunto I have called you, and the mission with which I have commissioned you.”

Turning now to Maeser’s story, I can clearly see he was one who allowed the Lord to instruct and prepare him in all things. As he did, he was then prepared to accomplish the many missions the Lord sent him out to, again and again — to serve as a missionary, mission president, teacher and founding principal of BYU.

Likewise, ours is an invitation to receive the Lord’s instruction, to place our “trust in that Spirit which leadeth to do good,” and in a very real sense: “enter to learn, go forth to serve.”

“I hope that all of our students leave with a clear understanding of who they are,” said current BYU President C. Shane Reese, as he spoke to my classmates and I for our documentary. And “that they understand their divine potential.”

There are “so many voices in our students’ heads telling anything but that,” he continued. “(But) if they understand how good they really are, and their incredible potential to go out into the world and make a difference — and serve God’s children in meaningful, powerful, impactful ways — I would be a happy president.”