Editor’s note: A version of this has been previously published on the author’s website.

Galaxies like to travel in clusters, multiple island universes bound together by gravity across many millions of light-years. “Clustering of galaxies seems to be the rule rather than the exception — about three quarters of all galaxies are in clusters,” according to NASA.

Class notes posted by professor Adam Burrows of the Princeton University Department of Astrophysical Sciences classify galaxy clusters as “poor” and “rich.” The former consists of tens of galaxies while the latter has thousands and is much larger than its poor cousin.

Our Milky Way Galaxy is part of what is termed the Local Group, an example of the poor type, which NASA says contains over 30 galaxies. Most are small (dwarf) galaxies. The Local Group stretches over almost 10 million light years, the agency adds. The dominant members are the Milky Way and Andromeda. “Also prominent in the local group is the Triangulum Galaxy (M33), Leo I, and NGC 6822.” Some of its members can be seen with modest telescopes.

Says NASA, “It is the proximity of some 50 nearby small groups of galaxies to the Virgo cluster that suggests that they all form an enormous flattened cluster of clusters; we call it the Local Supercluster.

“The Local Supercluster is actually centered on the Virgo Cluster of galaxies, which is why the Local Supercluster is sometimes called the Virgo Supercluster. Its equatorial plane is almost perpendicular to our Galactic plane. Our Supercluster, with a diameter measuring roughly 100 million light years or so, has a collective mass of about (10 to the 15th) times the mass of the sun.”

Space teems with clusters and superclusters of galaxies, and recently astronomers caught several supers in the process of forming a megacluster.

On Oct. 19, 2019, NASA announced the discovery of “a rare collision between four galaxy clusters. Eventually, all four clusters — each with a mass of at least several hundred trillion times that of the Sun — will merge to form one of the most massive objects in the universe.” The future megacluster, in a system denoted Abell 1758, is about 3 billion light-years from Earth.

Data from the Chandra X-ray Telescope uncovered a galactic shock wave in the hot gas of the system, the first detected. NASA likened the shock wave to the sonic boom radiating out from an aircraft reaching speeds faster than sound. Analysis showed that the clusters are zipping along at 2 to 3 million miles per hour relative to each other.

Other gigantic clusters of clusters include the Bullet Cluster, more than 4 billion light-years away, “formed after the collision of two large clusters of galaxies, the most energetic event known in the universe since the Big Bang,” according NASA; and El Gordo (the “Fat One), 7 billion light-years off, where two galaxies came together at millions of miles an hour.

“As with the Bullet Cluster,” write experts at NASA working with Chandra, “there is evidence that normal matter, mainly composed of hot, X-ray bright gas, has been wrenched apart from the dark matter in El Gordo. The hot gas in each cluster was slowed down by the collision, but the dark matter was not.”

Other impossibly enormous sections of the universe like galaxy “walls” — including the Sloan Great Wall, 1.5 billion light-years long — are not really structures, says a posting by NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. They just happen to be spread out in a line or arc. They don’t qualify as galaxy clusters or superclusters because “the components of it are not gravitationally bound together.”

Which brings us to my favorite galactic noncluster, the Deer Lick Group of galaxies.

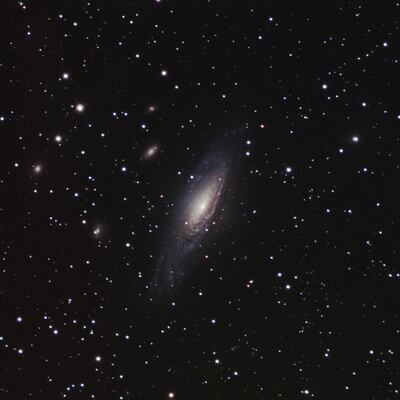

Located in the constellation Pegasus, the group is best viewed in the fall although its major component reaches well above the horizon before dawn in early May. That major component is the dramatic spiral galaxy NGC 7331, which the British astronomer William Herschel discovered in 1784. Although it is bright enough to glimpse with binoculars, oddly, Charles Messier never noticed it and therefore it is not on the Messier list, as other bright galaxies, star clusters and nebulas are. Distance estimate to NGC 7331 is around 45 million light-years, say Hubble astronomers.

The Austrian astrophotographer Johannes Schedler relays the story of the group’s naming: “Reportedly, Tomm Lorenzin, author of ‘1000+ The Amateur Astronomers’ Field Guide to Deep Sky Observing,’ gave the name to the NGC 7331 group in honor of Deer Lick Gap in the mountains of North Carolina where he observed and once had an especially fine view of this group of galaxies.” (Lorenzin, an avid amateur astronomer and author, died in 2014 in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, age 67.)

Kopernik Observatory in Vestal, New York, identified four galaxies as members of the group, besides the lovely swirl of NGC 7331:

• NGC 7338, the barred spiral galaxy that appears in my photo to the upper left of the main galaxy

• NGC 7335, a lenticular galaxy (an edge-on galaxy that looks like a lens), above NGC 7331’s center

• NGC 7336, a possibly lenticular galaxy to the upper right, near the top of the photo

• An unnamed galaxy below NGC 7331 in my photo, of unknown type and distance. (But I can see an apparent spiral arm, which would make it a spiral galaxy.) Kopernik says it’s sometimes considered to be a New General Catalog item called NGC 7325.

Five other features in the group were mistakenly considered galaxies in the past, the observatory adds. “Modern images show that five of the eight ‘companions’ are really just mis-identified stars or double stars. This error perhaps results from the poor telescopes used by the early observers.”

The illusory aspect of this striking group is that, despite appearances, it is not a galaxy cluster. As noted earlier, members of a cluster are bound together by gravity. NGC 7331, at 45 million light-years, is not an associate of the others, whose distances Kopernik places as varying from 332 million light-years to 365 million light years (and the dimmest, the unnamed galaxy, may be even farther off). They are too far away to bond with NGC 7331.

Joe Bauman, a former Deseret News science reporter, writes an astronomy blog at the-nightly-news.com and is an avid amateur astronomer. His email is joe@the-nightly-news.com.