SALT LAKE CITY — Justin Townes Earle stood outside the venue, smoking a cigarette.

He had just played a sold-out gig at the State Room in downtown Salt Lake City. Chris Mautz, one of the venue’s owners, still remembers how the muted street lights cast shadows on the gangly musician in the night.

“It was just sort of this live art that was happening,” he said.

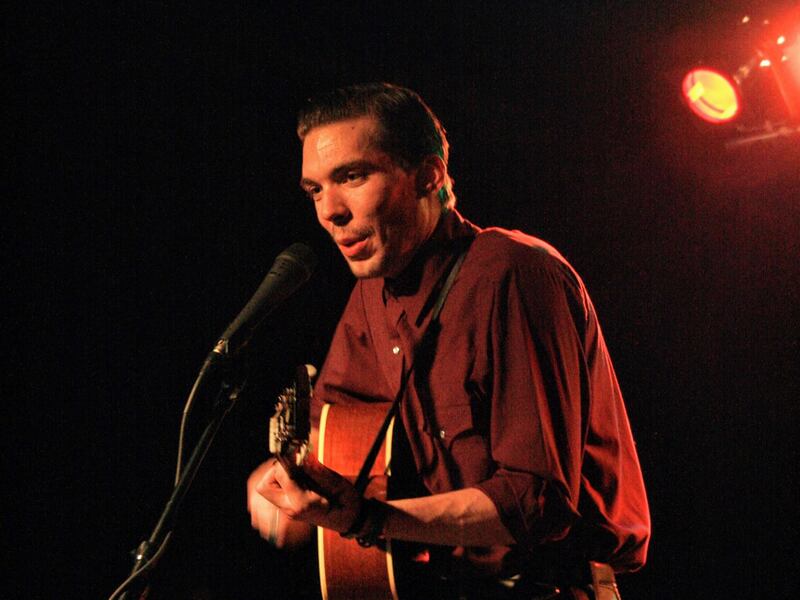

Earle may have once stood in the shadows of his father, famed country rocker Steve Earle. But over the years, he worked hard to emerge from that shadow. To be his own artist.

“I can’t imagine living in a world where your dad was such a force,” Mautz said. “It would take a lot of confidence to try to participate in that world. To step into it and be like, ‘You know what, I think I have something to add here, too.’”

At 38 years old, Earle had eight full-length albums under his belt. It’s hard for Mautz, who watched the singer-songwriter perform a handful of times at the State Room, to think about how there will no longer be new music from an artist who had so much to say.

“It’s a heavy place to go,” he said.

Earle died on Aug. 20. A few days later, police cited the cause of death as a “probable drug overdose,” according to Rolling Stone. Like his father, Earle battled drug addiction from an early age. He was open about his struggles — the highs, the lows and everything in between.

“I’ve never been a bashful person — obviously something I get from my father,” Earle told The Scotsman in 2015. “There’s nothing for people to figure out about me, no dirt for anybody to dig up about me somewhere in my past because I’ve already given it.”

In many ways, Earle followed in his father’s footsteps. But he also carved out his own path. He had a different way of presenting himself both onstage and off, Mautz said — a different kind of attitude and tone.

Mautz first met Earle in April 2009. The State Room had just opened, and Earle was the opener for Jason Isbell, who was headlining the venue’s second show. (That opening year would also see Brandi Carlile’s first of many shows at the State Room.)

“We didn’t sell out,” Mautz said with a laugh, noting that the venue sold between 200 and 250 tickets. “Looking back on that now, man, what a great night that was. Knowing now how each of their careers have really just matured and expanded.”

At that time, Earle was a budding musician — a few months after his first show at the State Room, he received an Americana Music Award for Emerging Artist of the Year. Over a decade, as Earle returned to that venue, and later, the newer Commonwealth Room, Mautz watched with fascination as Earle’s artistry evolved.

“He was such a physical presence onstage and was so enthralling. I think that quality only got better over time,” Mautz said. “And he was one of those artists that could really develop an album in a way that it had totality — it really meant something. He was such an authentic artist in my mind. Everything that he did, it felt so real to me.

“It was pretty remarkable how he was able to do that night in and night out.”

But it was the interactions offstage that stick with Mautz the most.

Whether it was watching Earle joke around during sound check, talking with the musician in the lobby or hanging out with him by the touring bus, Mautz was impressed with how easily Earle connected with others. Earle never seemed to be in a hurry, rushing from one venue to the next. He savored each moment.

“I can tell you, top to bottom, all members of our venues, if they had a chance to encounter and engage with Justin, it was always just so memorable and engaging,” Mautz said. “He was a great storyteller. You just couldn’t get enough of it. To me, it always felt like Justin’s space was being available and interested and visiting with other people.”

Earle came to Utah a lot. That 2009 show didn’t come close to selling out, but as he made a name for himself and started headlining shows, he drew a larger, dedicated crowd.

“It was always a show that we’d circle on the calendar and be so thrilled to be able to have him coming back,” Mautz said. “We had some really core fans, and those fans were such advocates of his music.”

Mautz believes Earle had a special connection with Utah and said the singer frequently talked about how he loved coming to Salt Lake City. One time, when Steve Earle played the State Room, Mautz recalled the veteran musician catching a glimpse of his son’s name on a poster backstage. Rather than being surprised, Earle seemed to know that his son had stood on that very same stage.

“I think it felt like one of his spots that really supported him, and that he always would look forward to coming back to,” Mautz said. “That came out in his shows here, the way he was able to really engage our local audience. Just lots of great musical memories.

“The hardest part is that there won’t be any more.”