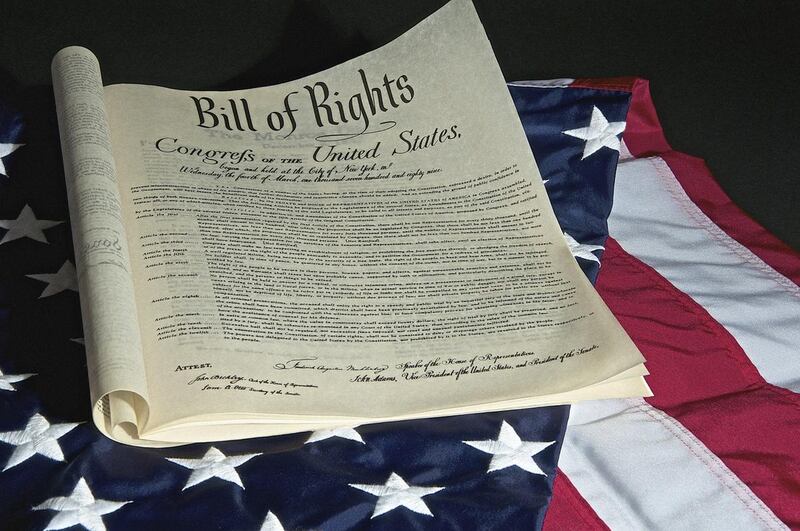

In 1787 and 1788, one of the principal objections to ratifying the Constitution proposed for the United States of America was its failure to explicitly enumerate guaranteed civil rights. George Mason, who had formulated Virginia’s Declaration of Rights, had actually proposed such a list, but James Madison had resisted. Madison’s most notable argument was that, if such an official list were included, any rights not specifically identified might be deemed unprotected. The Constitutional Convention sided with Madison.

Opposition to the proposed charter soon gathered, however, particularly in Virginia, Massachusetts and New York. (Approval from at least nine of the 13 states was required.) So, to meet opponents’ concerns, Madison formulated 20 possible constitutional amendments. One of his draft amendments read as follows:

“The civil rights of none shall be abridged on account of religious belief or worship, nor shall any national religion be established, nor shall the full and equal rights of conscience be in any manner, or on any pretext, infringed. The people shall not be deprived or abridged of their right to speak, to write, or to publish their sentiments; and the freedom of the press, as one of the great bulwarks of liberty, shall be inviolable. The people shall not be restrained from peaceably assembling and consulting for their common good; nor from applying to the Legislature by petitions, or remonstrances, for redress of their grievances.”

Madison’s 20 proposed amendments were ultimately reduced to 10, now called the Bill of Rights, and the text given just above was condensed to the First Amendment, ratified in 1791: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.”

Moreover, because the “establishment clause” and the “free exercise” clause, as they are known — both of which pertain to the freedom of religion — are mentioned first in the First Amendment, religious liberty has often been called the “first freedom.”

But what, exactly, does it mean?

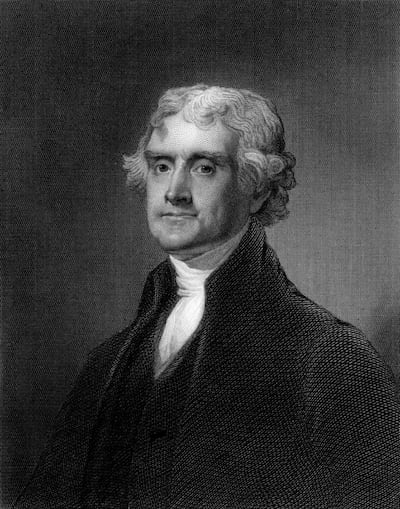

In late 1801, the Danbury Baptist Association, of Danbury, Connecticut, wrote to Thomas Jefferson, newly elected president of the United States. They were worried about religious freedom in Connecticut, where Congregationalism would remain the officially established church until 1818, with the state requiring all citizens to attend Sunday services and to pay taxes to support it (unless and until they demonstrated that their money should go to an alternative church or synagogue).

In 1802, Jefferson replied: “Believing with you that religion is a matter which lies solely between Man & his God, that he owes account to none other for his faith or his worship, that the legitimate powers of government reach actions only, and not opinions, I contemplate with sovereign reverence that act of the whole American people which declared that their legislature should ‘make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof’, thus building a wall of separation between Church & State.”

In 1874, Brigham Young asked George Reynolds, a future general authority of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, to serve as the defendant in a test case regarding polygamy. While researching for his decision in that famous “free exercise” case, Morrison Waite, the Chief Justice of the United States, found Jefferson’s letter to the Danbury Baptists, and he incorporated the notion of “a wall of separation between Church and State” into his ruling in Reynolds v. United States (1878). He also adopted Jefferson’s principle that, while the government can regulate actions, it has no authority over religious or other opinions.

As initially interpreted, the First Amendment referred only to the federal government (remember Madison’s ban on “any national religion” and its own “Congress shall make no law”) and not to the states. Thus, Congregationalism was the official church of New Hampshire until 1817 (into 1877, only Protestants could serve in New Hampshire’s legislature), of Connecticut until 1818, and of Massachusetts until 1833.

In the 5-4 decision Supreme Court in Everson v. Board of Education (1947), both Hugo Black’s majority opinion and Wiley Rutledge’s dissenting opinion approvingly cited Jefferson’s metaphorical “wall of separation between Church and State,” and the court now expressly applied that idea to the states as well as to the federal government.

But, again, what exactly does it mean? This continues to be a fiercely disputed issue.

Daniel Peterson teaches Arabic studies, founded BYU’s Middle Eastern Texts Initiative, directs MormonScholarsTestify.org, chairs interpreterfoundation.org, blogs daily at patheos.com/blogs/danpeterson, and speaks only for himself.