Editor’s note: Portions of this were published in a previous column.

One of the most obvious facts facing human beings is the inevitability of death. This certainty has led to the formulation of what some have called the “terrible question”: Is this life all there is? Are all the love, hopes, achievements and talents of an individual nothing more than transient traces left by a random and ultimately meaningless collection of neurons and biochemical processes? When our heart stops beating, do we simply cease to exist?

There are only two possible answers to this question: Yes or no. The secular perspective is eloquently summarized by Shakespeare’s Macbeth, for whom the close of mortal life was the absolute and irrevocable end. Upon hearing of his wife’s death, Macbeth exclaimed:

“All our yesterdays have lighted fools

“The way to dusty death. Out, out brief candle!

“Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player

“That struts and frets his hour upon the stage

“And then is heard no more. It is a tale

“Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

“Signifying nothing.” (“Macbeth,” Act 5, Scene 5)

Although agnostics may speak of the dead “living on” in the memory of the living, even this is cold comfort at best, for such memories of the dead survive only a generation or two. How many people remember their great-grandparents? And, of course, being remembered by the living is of no real consequence to the dead if they have ceased to exist.

On the other hand, nearly all religions affirm an existence beyond this one. Death is not the end, they say, but a transition to another state. Neolithic burials with offerings of food, flowers, clothing and tools demonstrate that the idea of an afterlife is one of the earliest forms of religious belief. The oldest surviving religious writings — the Pyramid Texts of Egypt — focus on the afterlife of the king, who ascends into heaven to dwell with the gods. Many ancients believed that dreams of the dead were real spiritual manifestations caused by the return of the soul.

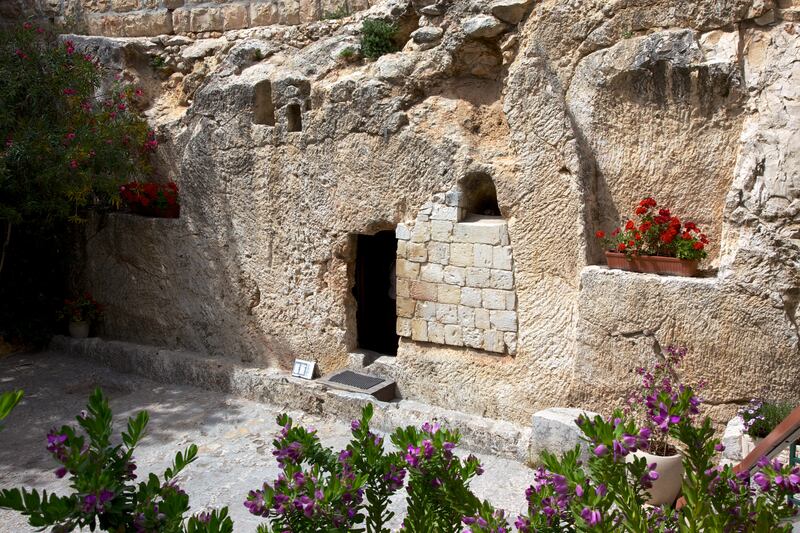

Most religions surround death with rituals of mourning and burial, of which there are numerous variations ranging from burial to cremation or exposure. For some, like the ancient Egyptians, corpses needed to be carefully preserved and protected to insure a proper resurrection. Many religions developed a “cult of the dead,” where the tombs of ancestors or holy men and women become shrines for pilgrimage, veneration and worship. The most enduring of these is the tomb of Abraham in Hebron, which has served as the site of ancestor veneration for nearly four thousand years. The actual bones or corpses of the dead have sometimes been preserved as sacred relics, imbued with the holy power of the dead saint.

Although most religions agree that there is existence after death, the precise nature of that existence is open to a wide range of interpretations. Many religions teach that family and loved ones will be reunited in the afterlife, for only with eternal love is eternal life worth living. For Hindus, death leads to a cycle of reincarnations of the soul, until, reaching perfection after countless lifetimes, the soul is reunited with Atman — the ultimate reality — in which individuality may be lost, but the spirit is absorbed into God.

Unlike the belief in reincarnation in eastern and southern Asia, the Near Eastern monotheistic religions — Judaism, Christianity and Islam — maintain that the dead will be resurrected and live forever. In addition, there will be a final judgment, in which those resurrected will be rewarded or punished for their faith and deeds during life. For Christians, Christ provides the answer to the “terrible question” in John 11:25-26, where he proclaims: “I am the resurrection and the life: He that believeth in me, though he were dead, yet shall he live. And whosever liveth and believeth in me shall never die.”

That, of course, is the point and the promise of Easter:

“He marked the path and led the way,

“And ev’ry point defines

“To light and life and endless day

“Where God’s full presence shines.” (“How Great the Wisdom and the Love,” Hymns, No. 195)

For believers, there is an amazing paradox in the terrible question: If we can answer this question in the affirmative — that there really is a life after death — the “terrible question” is marvelously transformed into the “wonderful answer”: that we may have eternal life. And, sooner than most of us are willing to admit, we will all make this marvelous transition — from life into Life.

Daniel Peterson teaches Arabic studies, founded BYU’s Middle Eastern Texts Initiative, directs MormonScholarsTestify.org, chairs interpreterfoundation.org, blogs daily at patheos.com/blogs/danpeterson, and speaks only for himself.