Sunday, May 29, 1983, 6:30 a.m.: A phone rings on the nightstand in the mayor’s bedroom. It can’t be good news, with a surge in warmer temperatures and record snowpack in the Wasatch mountains of northern Utah. Ted Wilson has spent enough time up there skiing and climbing and guiding others to visualize the day’s first light glimmering across the white surface, spawning droplets of water, forming rivulets that become torrents as they crash through the canyons above Salt Lake City. Nervous, he reaches for the landline.

A woman speaks, alarmed. She’s a city council member who lives in the Avenues, an older neighborhood of tree-lined streets and Craftsman-style homes on the hillside north of downtown, along the eastern rim of City Creek Canyon. Looking down on the park where that canyon ends, she describes a river gone insane, flush with snowmelt, bucking against its banks. If something isn’t done, and soon, downtown will be underwater.

City Creek is a small mountain stream, about 15 miles long, fed by runoff and natural springs, but it provided enough water to draw early settlers — members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints — to this corner of a broad and arid valley. Later, as the city grew into an urban center, its importance to farming faded. By 1909, City Creek had been channeled underground and out of the way. But that conduit was not built to handle a record 26-inches of water in a snowpack liquefying at a terrifying rate.

She describes a river gone insane, flush with snowmelt, bucking against its banks. If something isn’t done, and soon, downtown will be underwater.

Wilson knows the stakes. The month before, excess groundwater had cut loose the side of a mountain about 65 miles south, burying the small town of Thistle. And memories are still fresh of the 1976 failure of Teton Dam, 250 miles north in Idaho. There, after a 15-foot wall of water and rubble hit Rexburg, locals rallied together to help victims rebuild. What if Salt Lake City could mobilize them on the front end? “I need an army,” he thinks.

His first call is to Latter-day Saint church headquarters, a 28-story monolith a half-mile downstream from the park. A security guard answers. “I need to talk to the president,” Wilson tells him. It’s an odd request for the spiritual leader of more than five million souls worldwide, including most of the people living in the state of Utah at that time. “It’s Sunday,” the guard says, perplexed. “Why do you need to talk to the president?”

The mayor tells him: “Because I need him to cancel church.”

Forty years later, when I call Wilson, some Utahns are again casting nervous eyes to the mountains. Heavy snowfall across the West has interrupted a 22-year megadrought afflicting the region, and by April, the snowpack above Salt Lake City is more than double the annual average, far beyond the same point in time in 1983. To many, it seems their prayers for water have been answered. It’s hard to remember a time when they prayed for it not to rain, but it wasn’t all that long ago.

The flood of 1983 was caused by a perfect storm. All that winter, snow had piled up in record numbers. The resort town of Alta, 4,000 feet above the valley floor, recorded 637 inches from October through April, then the third-highest total since record-keeping began in 1944. No one, least of all the powder skiers, complained. Utah is the second-driest state in the U.S., with an average annual precipitation of 11 inches. Water is always welcome.

There’s typically an order to the process. Beginning in March, temperatures start to rise as days get longer, gradually sending snowmelt into the streams that flow into the reservoirs and water storage plants in the valley below. People who live nearby leave their windows open to hear the soothing sounds that herald the end of winter. But spring came late in 1983, and snow kept falling. Over 13 days in March and April, Alta added 12 more feet, as daily highs in the city hovered in the 50s, hitting the 60s only sporadically. But May 24 brought a hot streak, with daily highs surging into the 80s, cresting at 87 on that infamous weekend. Practically overnight, the seven major streams emptying into the Salt Lake Valley doubled, tripled or quadrupled their flow.

During a typical spring runoff, City Creek peaks at 45 cubic feet per second, with a flood stage of 90 cfs. On the morning of May 29, it was running at 230 cfs. Instead of 20,000 gallons per minute spilling into the underground conduit, the flow was at 104,000 gallons per minute. Any objects in the way — trees, boulders, debris, chunks of highway asphalt — were carried away as the stream rumbled down the canyon. The sound was anything but soothing. The soggy spring had left the ground waterlogged, unable to soak in much more.

Anticipating the worst, Salt Lake County had purchased more than a half-million sandbags and moved 50,000 tons of dirt to erect 10-foot-tall dikes along 1300 South, an east-west corridor 2.5 miles south of the park, closing off the street so it could turn into a river if needed. “By April we were very concerned about the potential for flooding,” says Bart Barker, the Salt Lake County commissioner in charge of public works in 1983. “We knew it was going to happen at some point. We didn’t know exactly what day or how bad it would be.”

“One minute we were in church, the next minute they said, ‘Hey, we’d rather you go down to State Street and help.’ I went home, changed into blue jeans and a T-shirt and was there within half an hour.”

Thirty minutes later, Wilson gets on the phone with President Gordon B. Hinckley, a member of the First Presidency, the church’s governing body. “I need every member I can get,” Wilson says. Calmly, the older man asks if the mayor might have a plan B. It is the Sabbath, after all. “Can you first give it your best try?” Realizing the gravity of what he’s asking, Wilson reframes the situation. “I hate to pull this one on you, but I would worry about your computers in the basement of the Church Office Building. It’s right in the flood path.”

“Now you’ve got my attention,” Hinckley says.

Soon Wilson and his aides are on the phone calling “every other religious leader we could think of. We needed all the help we could get.” Phones ring and services are canceled all over town, some stopped practically mid-prayer. “It was so crazy,” says David Dilts, who lived in the Avenues at the time. “One minute we were in church, the next minute they said, ‘Hey, we’d rather you go down to State Street and help.’ I went home, changed into blue jeans and a T-shirt and was there within half an hour.”

On the west side of the valley, Barker was still wearing his work shoes when he reported to church services in his neighborhood. He had been up much of the night, supervising the moving of backhoes and other equipment into flood-prone areas. He was there just long enough to hear the bishop close the meeting and send his congregants away. Soon he joined thousands filling sandbags and shoring up riverbanks along the Cottonwood creeks and other critical spots. “I don’t know where else that kind of volunteer response could have occurred in that short amount of time,” he says. “To watch it happen was soul-stirring.”

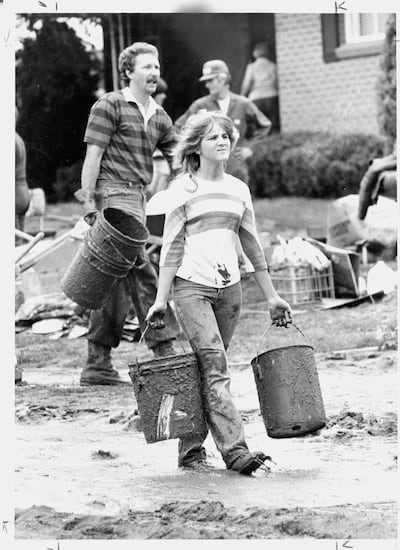

By the time Wilson arrives at Memory Grove, a thousand volunteers are already there, “some of them still in their church best,” he says. “We had guys taking their coats and ties off and jumping in to help, we had lovely Mormon women in their dresses.”

About 10,000 volunteers turn out downtown to build a makeshift riverbed. Believers, non-believers and sometime-believers — Latter-day Saints, Baptists, Catholics, Muslims, Buddhists, agnostics, atheists — stood side by side to form something like a conga line: one person holding the burlap bag, another filling it with sand, then passing it down the chain until it’s packed in place to form a temporary levee. By midafternoon, the sandbags are positioned, the work done. The only question: Will it hold?

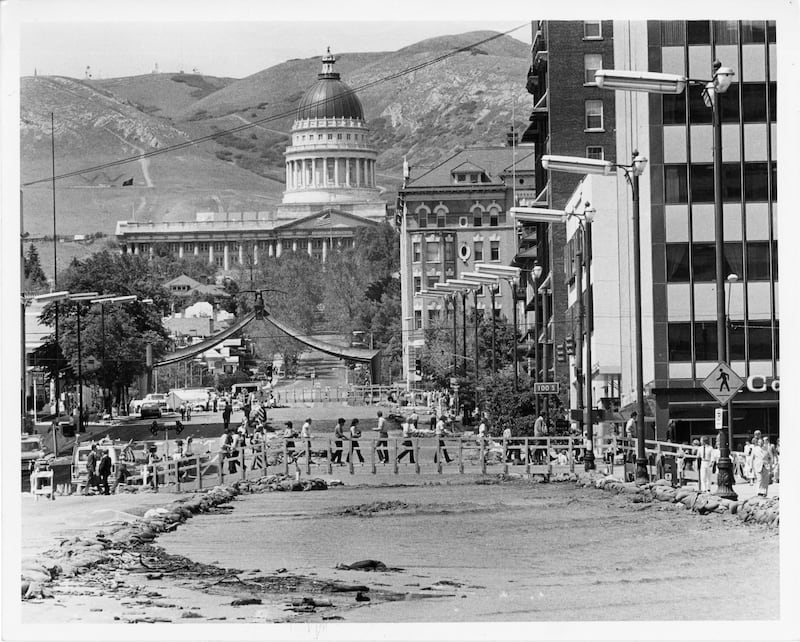

On State Street, Wilson’s wife sends word to her husband that the volunteers are getting impatient. “Where’s the water?” they chant. In Memory Grove, one final snag remains. The gate at the bottom of the lake is clogged and has to be fully released to divert the water in the proper direction. A brave city worker dons a bathing suit and dives in, swimming down to jimmy the gate. Freed, the water plunges south, rumbling past a 100-year-old building on the corner of South Temple and State to create what folks call the “Alta Club Rapids.” Realizing what they just built is actually working, the crowd exhales. Spontaneous celebrations erupt, kicking off what Wilson calls “the biggest street festival we’ve ever had.”

For 13 days, the new, improvised waterway redefined the city.. Pushing past two makeshift levees, the “State Street River” eventually stretched to 1300 South, where sandbags turned its course and led it two miles west to the Jordan River. Wooden bridges spanned its shore. Locals fished from its banks or ran the rapids in their kayaks. The national press descended on the scene, capturing the moment in Norman Rockwell tones. The Washington Post called Salt Lake City “The Venice of the high desert,” and ran a photograph of a young woman in a wheelchair who joined the human chain to help pass sandbags. More importantly, it became a monument to community spirit and cooperation.

Would Americans today pull together to save their city? Would they stand side by side to build a river? Another crisis could be the only way to find out.

Two years later, a report in the International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disaster, funded in part by a grant from the Federal Emergency Management Agency, found that widespread damage was greatly averted by the community effort. “The Salt Lake pattern for volunteer response to an emergency could be replicated in other places where there is a nonpublic organization, such as a church, that has a strong pyramid organizational structure, an adequate density of its members in the community, and the will to act.”

Volunteers continued to repair and maintain the levees from May 29 until June 11, when the State Street River ran dry.

Still, the striking memories of a city that overcame a crisis persist. Now 83, Wilson still has the sinewy frame of a mountaineering guide, but the country has changed around him. Would Americans today pull together to save their city? Would they stand side by side to build a river? Another crisis could be the only way to find out. With an easy laugh, Wilson remembers that first conversation with Hinckley, when the enormity of what they were facing sunk in — for both of them. “It turned out that having it happen on a Sunday was fortunate,” he says. “You got the feeling that by hell no flood was going to get us.”

This story will appear in the May issue of Deseret Magazine. Learn more about how to subscribe.