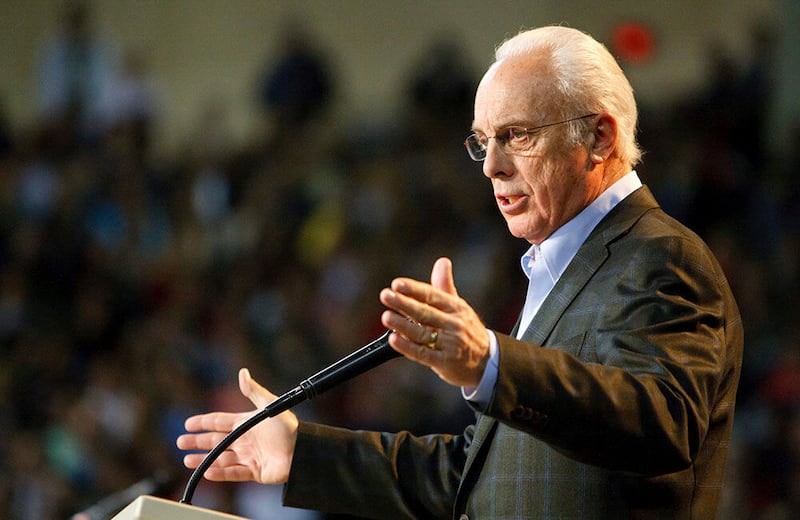

One quality that echoed through nearly every tribute I read about evangelical pastor Rev. John MacArthur was his relentless pursuit of truth through close and disciplined reading of the Bible. MacArthur, who taught at Grace Community Church in California for over 50 years, died last week at age 86. The outpouring of responses about MacArthur’s legacy made clear that his death left a deep mark on the evangelical community. But the very traits that earned him a devoted following also drew sharp criticism.

MacArthur refused to adapt his theological teachings and reading of the Bible to the times and never embraced the flashier, more emotional style of modern evangelical worship. Over the past 50–60 years, especially with the rise of the “religious right,” there’s been increasing overlap between Pentecostal and fundamentalist Protestant groups, two traditions that were once deeply opposed, Matthew Bowman, a historian of religion at Claremont Graduate University, told me.

Figures like Jerry Falwell, a prominent fundamentalist preacher who initially denounced Pentecostalism, eventually embraced some of its elements, especially as nondenominational evangelical churches began to adopt charismatic practices. As Pentecostal elements seeped into evangelical churches, Bowman said, MacArthur and other critics believed they led to “doctrinal fuzziness” and a kind of “laxity.”

In contrast, John MacArthur stood apart. He resisted the blurring of doctrinal lines and was a vocal critic of the charismatic movement, a trend within Christianity that emphasizes the gifts of the Holy Spirit, like speaking in tongues, prophecy, healing and miracles. He viewed the charismatic movement as a source of “bad theology, superficial worship, ego, prosperity gospel, personality elevation,” MacArthur said in an interview. “It promises to people what it can’t deliver and then God gets blamed when it doesn’t come,” he said.

Bowman described MacArthur as a “throwback” to what conservative Protestant Christianity in America was in the first half of the 20th century. “He was clear and precise in his doctrinal commitments to the tenets of early fundamentalism, and the Baptist movement in particular,” Bowman said.

Despite the criticism and backlash, MacArthur didn’t soften his message to appeal to broader cultural shifts. He opposed women preaching, LGBTQ identity and marriage, and took a hardline position on issues like abortion and social justice. “You cannot be faithful and popular so take your pick,” he said. On another occasion he said: “You love people if you’re telling them the truth.”

MacArthur, who preached in a suit, was known for his expository preaching, walking verse by verse through the Bible without detours into personal stories, remaining laser-focused on the text. “His confidence in scripture ignited my own,” one person wrote.

This kind of scripturally grounded preaching that MacArthur championed explains his sustained and broad appeal over nearly five decades.

“He showed to many young evangelicals how a real commitment to traditional conservative doctrine could translate into really clear and popular preaching,” Bowman said.

Term of the week: The Druze

The Druze are a small religious and ethnic minority in Syria, primarily concentrated in the southern region of Sweida province, that’s been at the heart of the war between Israel and Syria. Israel has publicly said that its military actions in Syria are aimed at protecting the Druze community, an Arab minority group with ties to Israel, per CNN.

The Druze is a religious group that emerged in the 11th century as an offshoot of Shia Islam, but quickly evolved into a secretive, closed faith with beliefs that draw from Islamic, Gnostic, Neoplatonic and other philosophical traditions. The Druze do not accept converts and are known for their tight-knit communities and strong internal cohesion. In Syria, they make up around 3% of the population, but they have historically played a significant role in national politics and military affairs.

Fresh off the press

- A district judge ruled last week to block the Washington State law that requires priests to break the seal of confession and report child abuse or neglect when it was disclosed to them during confession..

- My colleague Jennifer Graham reports on whether video games are making men more conservative. She cites a June report from the Speaking with American Men Project: “Algorithms fill the silence when no one else is listening, reinforcing ideas about manhood, power and worth before they’ve had a chance to define it for themselves.”

What I’m reading and listening to

- Ross Douthat interviewed Allie Beth Stuckey, an important voice on the Christian right and host of the Relatable podcast. Stuckey says she occupies “the space where politics and theology intersect.” The episode titled “Is ‘Toxic Empathy’ Pulling Christians to the Left?” is worth a listen (or reading the transcript) for anyone interested in the evolving fault lines of American evangelicalism.

- Elizabeth Bruenig makes a case against political candidate endorsement at church. “Church intervention in particular electoral races is an efficient polarization machine,” she writes.

- My colleague Natalia Galicza explores the meaning of identity and language in a recent essay. She writes: “I grew up around three languages: my mother’s Portuguese, my father’s Hungarian and our shared English. They each sounded like home to me, but we resorted to speaking only English.” And: “I felt two-dimensional to my relatives. How could I develop my own sense of self if I couldn’t understand or connect with my family?”

- “A Straight Line to the Pulpit: The Legacy of John MacArthur.“ “The church is his legacy, but so is an army of preachers and pastors all over the world. John MacArthur was able to bridge the sociological gap that befuddled so many fundamentalists. He was courageous, but unfailingly gracious in person,” R. Albert Mohler Jr., president and professor of Christian Theology at The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, writes in First Things Magazine.

Odds and ends

Over the weekend, I visited the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, and one painting in particular stood out. “The Golden Rule” is a portrait depicting a group of people of various ages, religions and ethnicities, it also features an inscription: “Do Unto Others As You Would Have Them Do Unto You.” It appeared in The Saturday Evening Post in 1961.

Although Norman Rockwell, American illustrator and painter, grew up in an Episcopalian family and sang in the choir as a boy, he wasn’t especially religious as an adult.

His words about the painting struck me as particularly timely today. “I’d been reading up on comparative religion. The thing is that all major religions have the Golden Rule in Common. ‘Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.’ Not always the same words but the same meaning.”