BOSTON, MA. — Robert George and Cornel West may be two of the most improbable friends in American public life.

George, a professor of jurisprudence at Princeton University, is a devout Catholic and a staunch conservative. West, on the other hand, is a passionate progressive intellectual — a professor at Union Theological Seminary, celebrated for his activism and critiques of inequality and injustice.

This unlikely friendship between the two professors started with a conversation about 20 years ago. A student at Princeton was launching a new campus magazine and invited West, who was at Princeton at the time, to interview a professor for the first issue. West chose George, whom he only knew only in passing.

What began as a planned half-hour interview in George’s office turned into a four-hour debate on philosophy, politics, literature and faith. The spirited exchange and the mutual intellectual affinity led to the pair co-teaching a freshman seminar called “Adventures of Ideas” based on 12 great books. West picked six books, and so did George. Students read Augustine’s Confessions, John Stewart Mill, C.S. Lewis, Martin Luther King Jr.’s Letter from Birmingham Jail.

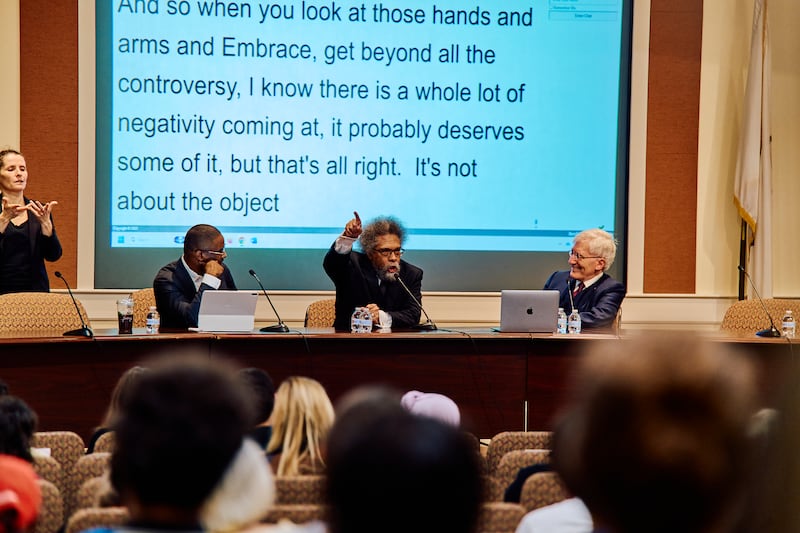

“From the first moment — some people talk about chemistry — we had magic,” George said, speaking alongside West on Wednesday night as part of Boston’s speaking series “Un-monument”, which brings temporary monuments and public programs to neighborhoods. Their conversation was inspired by the Boston sculpture called “Embrace,” which celebrates the legacy of Martin Luther King Jr. and Coretta Scott King.

Over two decades, the intellectual synergy between the pair’s student project blossomed into a deep friendship and an ongoing dialogue grounded in mutual love and respect. West and George know each other’s families, co-teach, travel, pray together, and now share a recently published book “Truth Matters: A Dialogue on Fruitful Disagreement in an Age of Division,” released this past January.

“Cornell West and Robert George have given us in their friendship and in their teaching a luminous model of what it means to live one of the most urgent but neglected dimensions of democratic life – the discipline of truth — seeking across difference,” said Brandon Terry, professor at Harvard University, who moderated the conversation.

“Love warrior”

It’s a question he often gets, West said, why “a conservative vanilla Republican” would spend time with a “chocolate hang-loose Baptist”, who is on the opposite end of the ideological spectrum.

“What I love about this brother is that even when he is wrong — that he’s honest,” West said, prompting a chuckle from the room. When many public figures tend to posture for attention or career gain, he argued, honesty and decency have become rare. “What happened to character? Character is destiny,” he said, citing Heraclitus, a Greek philosopher.

For West, the friendship and collaboration with George reflects his broader vocation to live faithfully, defending what’s true and serve “the least of these,” even when it comes at personal cost. In his remarks on Wednesday, West described himself as a “cracked vessel” striving to love flawed people with his “crooked heart.”

In 2021, West, who now teaches at Union Theological Seminary, resigned from Harvard University after he said that the school denied him tenure. In his resignation letter, he accused the school of “intellectual and spiritual bankruptcy of deep depths.”

After public pressure, Harvard offered to reconsider his tenure, but West had made up his mind. West has also taught at Yale and Princeton. Among West’s most known books are “Race Matters and Democracy Matters,” his memoir “Brother West: Living and Loving Out Loud” and his most recent book “Black Prophetic Fire.” In the 2024 presidential election, West announced his candidacy as a progressive independent, finishing seventh in the national vote.

West often frames his life’s work as part of the same tradition of " great Black people" that shaped Martin Luther King Jr. and Coretta Scott King — “love warriors,” according to West. He is part of the same lineage, he said, describing himself “as a redeemed sinner with gangster proclivities.” For him, figures like King, James Baldwin, and Toni Morrison embody the same spirit of transforming suffering into love and joy.

Are we in the age of feeling?

Just as the medieval era was known as the age of faith and the Enlightenment as the age of reason, George argued, that today we are living in what he calls the “age of feeling.”

“Many people seem to think that the touchstone of truth and goodness or justice is healing, is emotion, is how they feel about something,” George said. “For many people today, moral guidance, even wisdom, is sought in feeling and emotion. And I object.”

Although George doesn’t dismiss emotion outright, he warns that when feelings aren’t disciplined by reason, they can easily lead us astray.

“ If we are guided by our emotions, we’re guided by our feelings, we’re guided by these subjective features of ourselves, we have no very reliable source of truth,” George said.

And while even the most reasonable of us get things wrong, for George, reason is a steadier guide than emotion: “My belief is that the least reliable way to find the truth is to consult your untutored feelings.” In the relationship between emotion and reason, he noted, it’s reason that should be in the “driver’s seat.”

He calls for a return to the “medieval ideal,” in which faith and reason work together with what Pope John Paul II once described as “the two wings on which the human spirit ascends to the contemplation of truth.”

West, however, suggested that a purely intellectual orientation might stand in the way of deeply loving others. He described today not only as the age of feeling, but as an “age of nihilism.”

“Nihilism is the concrete experience of lovelessness and meaninglessness, touchlessness and not being able to cultivate the capacity to love one’s neighbor,” West said. Without strong institutions, cultural virtues and deep values to curb greed and indifference, West said, societies risk becoming nihilistic, governed by a “might makes right” mentality.

Decay of culture and value of truth

Amid this growing nihilism, the temptation might be to embrace the mindset of “you have your truth and I have my truth,” George said, but this thinking in his view is misguided.

“If there is no such thing as the truth, there is no way for you to offer me any challenge or criticism — there is no rational basis for you to ask me to rethink, reconsider, to give me an argument, to induce reasons, or marshal evidence,” George said. “I’ve essentially immunized my beliefs against challenges, against revision.”

When we shield ourselves and our beliefs from critique, this thinking could slide into dogmatism, he said, and even authoritarianism.

Young people are steeped in the culture “that produces a joyless quest for insatiable pleasures,” West warned. They’re stimulated in various ways, yet “their souls are still empty, their hearts are still vacuous.” West called joy “a spiritual achievement,” because love, which precedes joy, requires learning and knowing “how to empty yourself to receive and give.”

In a culture that West described as “spiritually hollow,” politics has become a byproduct of broader trends shaped by consumerism and greed. It’s this culture that gave rise to Donald Trump, he noted, where he is less an anomaly than a symbol of broader cultural decay.

“He hates all the time, well he’s been hated on too by the corporate media,” West said. “Oh, ‘he’s attacking Harvard’ – when was Harvard the bastion of truth?”

In 2017, he controversially referred to the Charlottesville marchers as “brothers.”

“I don’t ask anybody’s permission as (to) who I call brother or sister who I love, and I’m a Christian. God loves you, just like God loves me,” West said. “It’s not a question of pointing fingers — you have to be self-critical. You have to examine yourself.”

Instead of chasing pleasant experiences, George makes the case for a life grounded in reality as opposed to one driven by falsehoods or fantasies. But this commitment rests on faith, he said. “I have faith in reason,” he said.

He urged the crowd to embrace the real world “even when it’s tough, even when it’s hard, even when it’s challenging.”

In wrestling with reality, each one should commit to the pursuit of truth: “The vocation of every single one of us to be a determined truth seeker and a courageous truth speaker. And we can’t be one without the other.”

Early abolitionists in 19th-century Boston exemplified truth-telling, West said. They were initially dismissed but later recognized for their moral courage.

He homed in on the question our nation is facing: “How do we become more courageous in our fallibility, in our willingness to bear witness and staying in contact with humanity, even of the gangs, who are promoting injustice?”

Why do I believe what I believe?

To become truth-seekers, George advised to first acknowledge our fallibility – that we are “undoubtedly” wrong about some more important questions about existence and human nature. Then ask: why do I believe what I believe? Is it because it’s what my tribe believes or because of what the culture believes?

Many historically “smart, sophisticated” institutions like Harvard, Princeton and major foundations actively supported eugenics, George said, and it was only after Hitler discredited eugenics that society began to repudiate it. “The only way we can be that self-critical is if we cultivate in ourselves the virtue of intellectual humility.”

The years of debating with George have helped West get “inside his skin” he said. Even though he hasn’t changed his core views, he’s gained appreciation of nuances and insights he’d previously overlooked. “There is still some real possibility of maturing,” West said. ”You have to undergo serious self-examination and contestation in order to become more ripe and more mature to grow and develop spiritually more politically and that’s one of the great gifts I’ve had with my brother.”

American exceptionalism, George explained, is not about claiming superiority but about uniting a diverse nation around shared ideals rather than common ethnicity or religion. Losing this fragile foundation, he warned, would leave the country with nothing.

“ If we back ourselves into a situation where we have to regard them as enemies and aliens, then there’s nothing to base our national unity on, and we will sooner or later fall apart.”