Laura James grew up in a tight-knit Caribbean neighborhood in New York City, where her family attended a local Brethren church. The denomination, which traces its roots to 18th-century Germany, practiced an austere form of worship: bare walls, a piano, unadorned window frames. The only pop of color came from children’s Bibles, where Jesus was depicted with yellow hair and Black people looked gray, typically portrayed as servants.

James, an artist and illustrator of Antiguan heritage, felt disconnected from these images and eventually, the faith itself. “It wasn’t about me,” she says. “This did not seem like anything I wanted to do with.”

Later, in her neighborhood bookstore, she stumbled on a book of Ethiopian Magic Scrolls. The images of Black angels on the cover captivated her. She began teaching herself to draw in the Ethiopian Christian style, attracted to its spiritual power and Black imagery.

Over more than 30 years, she’s developed a distinctive style that blends the vivid colors of Caribbean art with the nonrealistic, folk-inspired forms of Ethiopian Christian tradition. Her work resonated with the broader Christian community and she was asked to illustrate the Book of the Gospels for the Roman Catholic Church.

“I’m happy to show a different perspective on the Biblical characters, because we’re all made in God’s image, so that to me means that we’re all different colors,” she told me.

James’s paintings of Jesus are part of “Expressions of Jesus: Cultural Representations of the Savior of the World,” a newly released collection from Deseret Book that highlights how over 100 artists from different cultures, historical periods and religious backgrounds have depicted Jesus. Alongside paintings by Danish painters Carl Bloch and Frans Schwartz are early Christian works by unknown Syrian and Greek artists, Renaissance masterpieces, Ukrainian and Russian icons, and contemporary artists from Africa, Ghana, Ethiopia, Peru, Argentina, Mexico, and beyond.

Together, these images highlight a broader shift in American Christian art — away from depicting Jesus solely as European and toward reimagining Him through the traditions, cultures and lived experiences of believers around the world, while also bringing these diverse representations into worship spaces and religious literature.

“The whole vision of this book is that Christ is for everyone,” says Rose Datoc Dall, the artist who curated the book.

A growing movement

Although white, European-looking depictions of Jesus have dominated Western Christian art for centuries, it wasn’t always this way. Early portrayals showed him as a short man with olive skin, curly hair, and no beard, often wearing a simple tunic. But as Christianity spread through Europe, and as anti-semitism grew, artists increasingly presented Jesus and Mary with fair skin and European features.

Today, a growing movement among contemporary artists, particularly within Christian traditions, is working to move beyond the Eurocentric portrayals of Jesus and other Biblical figures. For years, such efforts remained largely outside the mainstream conversation, says Esther Hiʻilani Candari, an Asian American artist from Hawaii whose work appears in the book “Expressions of Jesus.” But the energy around culturally diverse portrayals of Jesus has increased.

The turning point came in 2020, Candari observed, as the nation wrestled with its racial history in the wake of George Floyd’s killing. This nationwide reckoning also prompted a reevaluation of the long-standing portrayal of fair-skinned European Jesus in religious art. “It opened up that conversation to lots of different venues, including our religious spaces, and I think people started asking themselves bigger questions,” Candari says.

Rose Datoc Dall, Filipina-American artist who curated the art in the book, was among those artists. It was around 2020, that she felt compelled to paint Jesus more as a Middle Eastern man. “I feel like for me as a person of color, it would be appropriate to portray Jesus as Middle Eastern,” she told me.

The choice is personal, a matter of her artistic interpretation, says Dall, who describes herself as a contemporary figurative artist, influenced by bold colors, cinematography, theater and pop culture.

This shift toward more diverse images of Jesus was a source of inspiration for other artists, Candari says.

“I think we sometimes forget how much an image can communicate about an idea,” Candari says. “I think when people aren’t given the opportunity to see God depicted in a variety of ways, but especially in a way that reflects them in their culture, it makes that truth feel more distant and less personal.”

That doesn’t mean getting rid of all the images of Jesus where he’s depicted as white, she clarifies. “What I’m arguing for is that you can’t put God in a box,” she says. “We need to take God out of a box and make that reality accessible to everyone.”

Dall says she was surprised by the breadth of Christian art she had discovered while assembling images for the book. “Artists are expressing their love for Jesus through their own vernacular,” she says.

The “Expressions of Jesus” collection is the first of its kind, according to Laurel Day, president of Deseret Book Company, who spearheaded the project and surveyed the religious art book landscape before embarking on assembling the collection.

The purpose of the book, she says, is not to debate the historical accuracy of Jesus’s appearance, but instead to unify around the messages of Jesus and his life. During the time of division and uncertainty, she believes, the book’s message is especially timely.

“I’m hoping that this is a reminder that Jesus is the Savior of the entire world and that there is no single image or tradition that is more powerful than the next,” Day says.

Specific and abstract Jesus

“If Jesus appeared in China, would he speak Chinese?”

“Does Jesus even know Chinese?”

These were the questions that Chinese artist Julie Yuen Yim got asked when she was serving a mission with her husband for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Beijing, China. The members were “strong,” she says, yet they felt “segregated” from a larger church, she told me.

After these experiences, Yim, who received her art degree from Brigham Young University and now lives in Hong Kong, decided to try painting Jesus as a Chinese man in a traditional setting to help believers in China connect with their faith. She also turned to traditional art techniques — Chinese brush painting and paper cutting.

In her painting “Suffer Little Children III” that’s featured in the book, Jesus, shown as a Chinese man wearing traditional clothing, is surrounded by children. In the backdrop are a Chinese pine tree, a symbol of longevity in Chinese culture, and oxen, alluding to humility and lower status, Yim explained.

The painting’s title is written vertically, following the style of traditional Chinese artworks. “The message I want to get across is not what he really looks like, but that he’s God of all people,” says Yim. “I really hope that I’ll help people to realize that Christ loves them, whoever they are, wherever they are.”

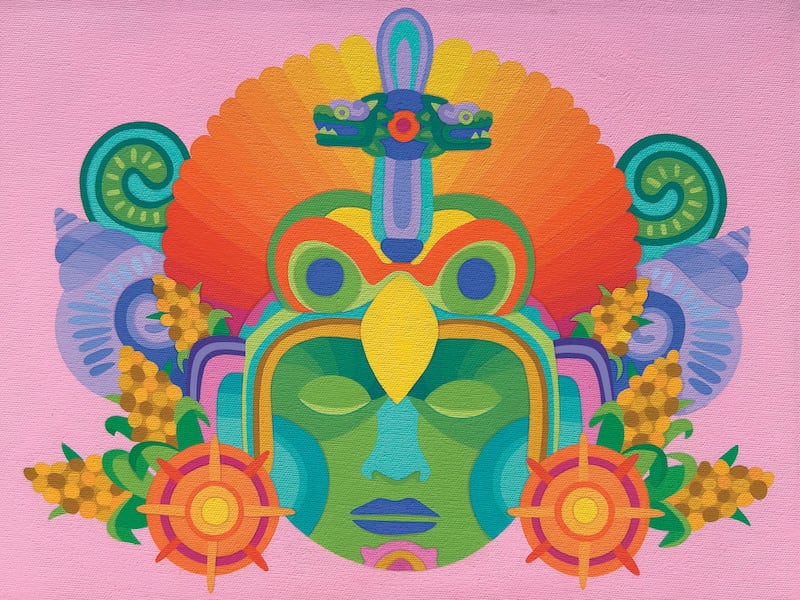

Others have infused their portrayal of Jesus with less obvious symbols. For example, Mexican artist Lourdes Villagómez used corn as a symbol of life and sustenance, “showing how God nourishes us daily,” she says. She blends Christianity and Mesoamerican symbols in her image of Jesus, using bold color and elaborate shapes. Motifs from Mexican tradition like altars and flowers in her work nod to Mexico’s Catholic devotion.

“Culture gives form, but faith gives the foundation,” Villagómez says.

For some artists in the collection, it’s through the more abstract forms that believers can connect with Jesus in a more personalized way. Jorge Cocco Santángelo, Argentine artist, started out painting in a more conventional realistic style, that he says was more widely embraced by the church. But over time, he “dared” to create his own style he calls “sacrocubism,” where he draws on elements of cubism in painting religious subjects.

He prefers abstraction to specific settings, lines, colors and forms to convey the emotional and spiritual essence of Jesus — leaving the viewer to their own spiritual experience. He’s also cautious about imposing his own vision of Jesus on others. “The world of abstraction offers an unlimited richness of expression,” Santángelo wrote in an email.

American artist J. Kirk Richards echoed the sentiment. In painting Jesus, he’s ultimately after capturing what the presence of Jesus might feel like. Richards says he’s seeking a balance between “idealistic” classical elements and more “gritty” realistic details as well as abstract symbols that hold deeper spiritual meanings. He also thinks of current events, Jesus’s teachings and skin tones.

“I know we talk about Jesus as being from a specific time and place,” Richards says. “But also sometimes I just try to make it so that he is from no place or every place.”

Exposure and education

Laura James recalled a recent visit with the group of young students from North Carolina, who came to tour her New York City studio. She was excited to see this group — mostly white — nodding their heads and really “get” her Ethiopian-inspired work with Black figures, Jesus among them. “They totally appreciated everything that I was saying,” she says.

Over the years, James has heard from people who said that her paintings made Jesus feel more accessible and that helped them feel more welcome “in the Christian family.”

“When a church bulletin features my work, it shows that they recognize God and Biblical figures can be depicted in any race — because, actually, we’re all different,” she says.

She’s an advocate for broader education and exposure to artistic traditions as a way to deepen understanding and connection. “We need to not be afraid of one another,” she says.

One of her favorite pieces from The Book of the Gospels she had illustrated for the Catholic Church is called “Love One Another.”

“This is what Jesus says we’re supposed to do, you know?,” James says. “So let’s do that already.”