A new mother in 2007, Argentine artist Susana Silva felt joyful, but overwhelmed.

She had spent several years studying and practicing her craft in art and painting, but suddenly she felt at a loss of physical and mental strength to pick up the paintbrush and continue.

She was “completely exhausted.”

“I thought I could no longer do anything,” Silva recently told the Deseret News. “I had no brain, no energy.”

Nearly two decades later, Silva said she recognizes it was this precise period of time that pushed her to test her possibilities, eventually leading her to develop her skills in hand-cut paper — a delicately intricate technique that has earned her multiple awards, and most recently, enabled her to collaborate with her artist brother on an exhibition that has traveled to New York and is now in California.

Thus for Silva, motherhood has symbolically become one of the many perforated paper layers, which like in her artwork, have been intricately cut and assembled together to shape and direct her life as an artist, mother and woman of faith.

Silva’s life sketch

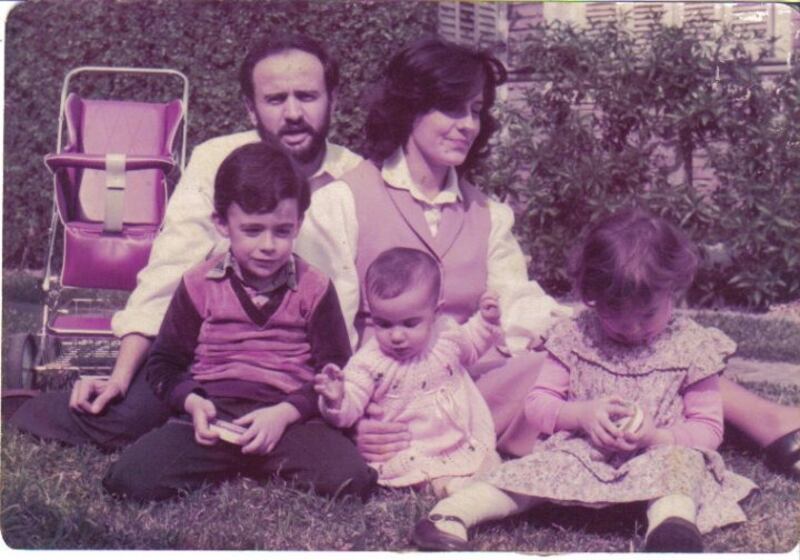

From the very start, Silva’s life was filled with color.

Her parents — though neither artists by profession — were “very artistic” and procured diligently to create a home where Silva and her four siblings could grow up surrounded by art, music and literature.

“(My mom) is a woman of many colors,” Silva said. “She’s always listening to music. … (And my father), he was a painter, photographer, writer and lyrical singer.”

Yet despite growing up in an art-filled home, Silva explained that when faced with choosing her own career at 18 years old, art was not her “first choice.” It was graphic design.

So she began studying at the University of Buenos Aires. But losing her father to suicide just months later, Silva’s studies quickly came to a halt.

“Almost without thinking, I began working right away,” she said, explaining that both she and her older brother paused their studies to work and put food on the table at a time their family was struggling financially and with the death of their father.

This period of time was understandably hard for Silva and her family, but she said it was one that helped her define her path.

“It was like a pause that helped me redirect myself,” she said. “(And) many good people — angels, one could say, that the Lord put by my side — helped me a lot during that time.”

One such angel was Silva’s friend Alicia. She was an older woman and had studied graphic design at an art school, so she encouraged Silva to take the school’s entry exam.

Silva did so. And to her surprise, she ranked second among all applicants.

“I couldn’t believe it,” she said. “I had sung lyrical opera, had danced some classical dance, had done many things but generally always within music, not visual arts.”

Silva began in the graphic design program, coursing “many artistic classes beyond graphic design” in her first year.

“It was then,” she said, “as I experimented with sculpture, painting and printmaking, that there was no turning back.”

By 1996, Silva had decidedly “abandoned” graphic design to fully pursue art, and that shift, she said, was “absolutely wonderful.”

“(Through art), I found not only a means to express myself and to manage what I was feeling at that moment, but I discovered I had a resource to talk about things that were important to me.”

These things, Silva explained, have included social issues, personal hardships and faith-based narratives, all of which have been inspired by her own life experiences and observations, as well as her faith as a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

How motherhood reshaped Silva’s art practice

For Silva, becoming a new mother in 2007 was a stretching journey.

She had married in the year 2000 and then dedicated years to developing herself in art — earning a degree in visual arts, continuing her studies at the National University of the Arts, and attending various workshops and seminars. But in an instant, Silva explained, motherhood brought new demands.

“I felt completely exhausted,” she said. “(And) it was so overwhelming at first that I thought all of my development in art had been left behind.”

Yet, after a nearly two-year pause from creating, Silva said an artist friend of hers urged her to return to the easel and canvas, and paint.

This friend “literally pushed me to her incredible studio,” Silva said, speaking of her friend Cecilia.

It was at that point when Silva began to paint again.

Still, making a consistent effort to return to the canvas had its challenges, she explained. Silva would find it hard to regularly commute to the studio, and on the days she tried painting at home, little hands would often interrupt her work.

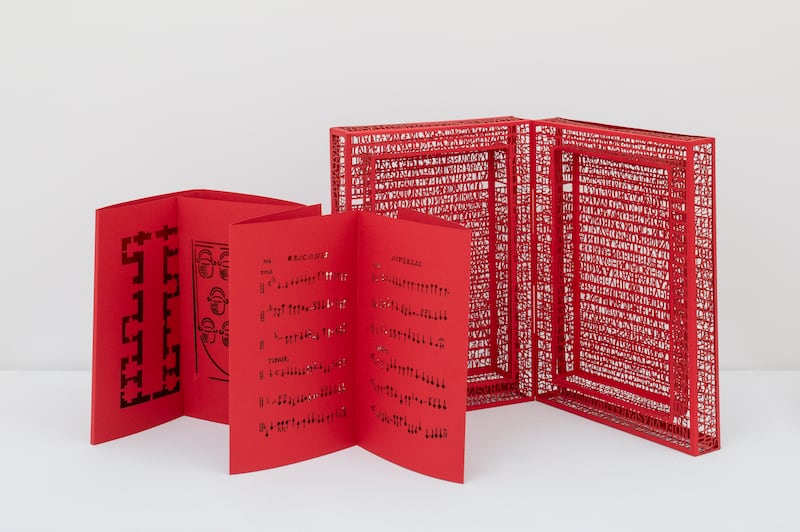

Roughly two years into her return to art, Silva began experimenting with paper, cutting shapes and assembling them together.

“I began testing my possibilities with paper, first in one layer — always working with abstraction, the line, the rhythm,” she said. “And then I began experimenting with space, incorporating layers to create 3D works.”

This process of exploration took years of learning and fine-tuning, she continued. But it ultimately enabled her to blend her two worlds, strengthening her capacity to be “truly flexible (and) elastic” as an artist and a mother.

This new technique “allowed me to work in small segments and then assemble them,” Silva said. And this became “my way of being able to be with my kids,” she added, explaining that she would often work from a board she set up in her kitchen.

There, Silva said she was able to cook, attend to her kids, help them with their homework, sit down to work and “not give up, not have to decide between one thing or another.”

“I needed to assemble everything together and for me it worked. … It became my way of being able to do it.”

The role of faith in Silva’s artwork

Growing up as a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Silva said religious themes in art always interested her.

In fact, she said that even as her family stepped away from the church when she was young, she would often dig through old church magazines and tear out any art so she could keep it.

“It was beautiful,” she said, adding, “It always enabled me to learn about the gospel.”

Silva’s interest in religious art, she explained, led her to replicate and adopt religious themes in her own artwork early on. But as her work moved toward abstraction, she said such religious themes faded, as she was unsure how or if she could depict them.

Roughly seven years into developing her paper cutout technique, however, Silva decided to try integrating religious themes into her art once again.

Since then, she has submitted her work to various religious art competitions, receiving awards such as the Acquisition Prize at the 11th, 12th and 13th international art competitions put forth by the Church History Museum in Utah. And she has also had her art included in a variety of publications and exhibitions.

Through each creative experience, Silva said she has seen both her faith and art strengthened.

It’s like a “symbiotic” relationship where there is “continuous nourishment,” Silva said, explaining that that kind of mutual nourishment often manifests itself in each stage of her creative process.

In her research stages, for instance, Silva said she often has conversations with friends and others where she can exchange ideas and spiritual understanding.

These conversations have, in many cases, “led me to reflect on things I would not have otherwise,” she explained.

Time and experience have also taught Silva that the fluidity of her work depends on her spiritual connection and reliance on the Holy Ghost.

“The Spirit, what it does for me, is help me to connect the dots,” she said. “And if one is connected with heaven, it is easier for the ideas to transmit and the resources to come.”

How Silva’s artwork traveled from Argentina to New York

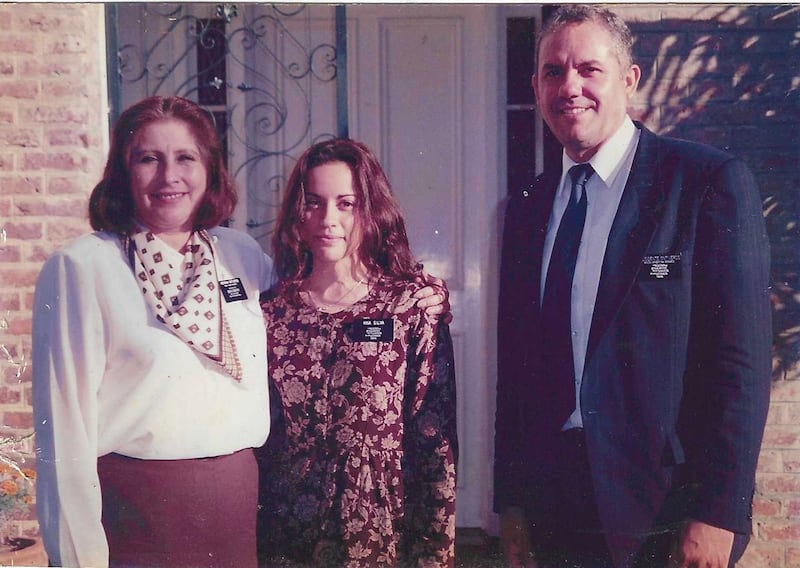

Both Silva and her younger brother Gonzalo — also an artist — were awarded the 2023 Ariel Bybee Endowment prize by the Center for Latter-day Saint Arts.

This endowment prize recognized their proposal to create an exhibition that would explore how memory and music were used to capture and codify the changes of colonization in their home country of Argentina.

But from the time they joined creative minds to come up with their proposal, to the time they saw their exhibition unveil in New York this August, both Silva and her brother said this endowment prize gave them the opportunity to stretch and strengthen their talents, as well as their relationship as siblings.

“This was the first time we worked together,” Silva said, recounting the many hours they spent researching, testing ideas and working to combine their distinct techniques to create one cohesive exhibition.

Recognizing the two grew up 15 years apart, Silva’s brother Gonzalo added that the process helped them connect both as artists and siblings.

“(Growing up) we really never had much time to connect,” he said, “so this became an opportunity to get to know each other better, too.”

Silva’s and her brother’s exhibition was open in New York for a couple of weeks in August. Starting Oct. 10, the exhibition opened in Berkeley. Find more details about the artists’ exhibition here.

Silva’s advice to mothers

Recognizing that her own motherhood journey was an “enormous” leap of faith, and that each mother’s journey is unique to them, Silva’s main advice to all was to “be patient.”

She acknowledged mothers face “great social pressure,” and shared that even she had delayed having kids for fear of not measuring up to her own expectations and mother’s example.

Mothers should “be patient with themselves and give themselves time to find a path forward,” she said. As they do so, that “path forward will come,” and they will see that “sometimes one doesn’t need to force it so much, it’s more organic, … intuitive and beautiful than one could expect.”

Adding to her advice, Silva also said mothers should realize they have the Holy Ghost with them “more constantly” than they think, and that many times their lives’ events are “being entirely led by the Spirit.”