Political scientist Charles Murray describes himself as spiritually “handicapped.”

The realm of spiritual experience that others seem to navigate with ease has been cordoned off from him, he told the Deseret News in a recent interview.

Yet, after decades as a self-described agnostic, Murray has begun to confront religious questions he once regarded as out of bounds in the only way he knew how — through reason and scholarly inquiry.

Murray, who is now 82 and is a fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, first gained attention with his 1984 book “Losing Ground,” in which he argued that welfare programs often worsened poverty and sparked intense policy debates. In 1994, along with author Richard Herrnstein, Murray co-authored “The Bell Curve,” which examined the role of intelligence in shaping social outcomes and drew sharp criticism for the discussions of race, IQ and inequality. His 2020 book “Human Diversity” explored the science behind genetic and cognitive differences among different groups, and implications of these differences for society and public policy.

In his newest book, “Taking Religion Seriously,” published last month, Murray details how he came to belief by rationally examining the origins of life, the legitimacy of paranormal and near-death experiences that point to the existence of the soul, and the historicity of the Gospels, including the event of Jesus Christ’s resurrection.

“Taking Religion Seriously” follows Ross Douthat’s “Believe,” which similarly makes a rational case for faith to the skeptics, and Rod Dreher’s “Living in Wonder,” a case for reviving a sense of wonder in the modern world.

Murray, who now describes himself as a Christian, grew up Presbyterian in Iowa. By the time he graduated high school, he had been confirmed and spent a few weeks at a Presbyterian summer camp.

But still, faith never took root. As a student at Harvard University, he absorbed the prevailing secular view that smart people didn’t believe in God. But things began to shift when he got married and became a father.

“Whatever else may be said about Mr. Murray, he can’t be accused of dishonesty and cowardice,” according to a recent Wall Street Journal review of the book.

Murray spoke with the Deseret News recently. This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Deseret News: I have to start by saying that the cover of your book features one of my favorite paintings, “The Monk By the Sea” by Caspar David Friedrich. How does it reflect the themes in your book?

Charles Murray: It captures the book because it’s the picture of me, in a way, staring out to sea and trying to make sense of a spiritual world that in certain respects is closed to me because of what I call a “perceptual deficit” in the book.

DN: That’s right. You write: “I suffer from a perceptual deficit in spirituality.” How did you first come to realize that you had this lack of perception for spiritual things?

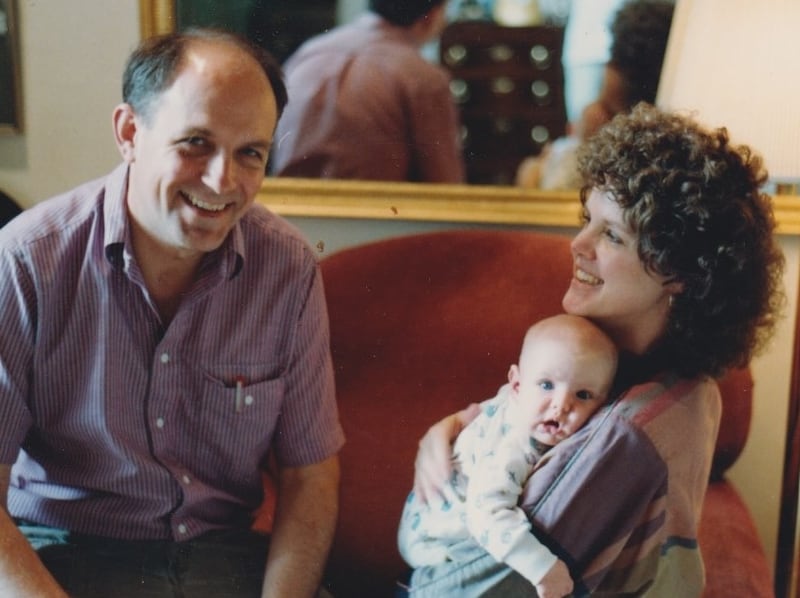

It’s my wife. My wife Catherine is at the center of everything that the book led to. After the birth of our first child, she decided that the love she felt for our daughter was beyond anything she’d experienced. And as she put it, “it was more than evolution required.”

And she saw that as being a conduit for a larger love that she identified vaguely with God. And she set out to explore various aspects of Christianity, which she eventually did find and became an active, spiritually active Quaker. She just had a steadily deepening understanding of what she believed and why she believed it.

I wanted to participate in that, because I could see that she was drawing a lot out of it.

But I could also see that she was capable of doing contemplative prayer or reading texts that she took a lot out of that I didn’t. It wasn’t that she was making stuff up — she was perceiving things I couldn’t.

It’s similar to music. When I listen to great music, like Mozart or Beethoven, I like it a lot. But do I hear it the same way that a violist friend of ours hears the music? No, I don’t. My violist friend could enter into the music, fully appreciated its power, its emotion in ways I can not.

And that’s when I developed the idea that spirituality is a trait and I’m handicapped. I think it’s good for people who are nonbelievers to take that idea on board.

Because I think, nonbelievers too often look at people who are deeply religious and assume they’re making it up. They think the nonbeliever is a smart one and a rational one. And people, who are deeply religious — too bad for them, they are just out of touch with reality.

Well, I’m saying: You got it wrong and you do not appreciate the degree to which you yourself suffer from a perceptual deficit.

DN: So you think the ability to have spiritual experiences is inherent?

CM: Yeah, I think it’s a trait like any other human trait. And at the extremes, no one doubts that the ability to appreciate great music or great art is a trait because there is such a thing as being tone deaf. That’s a physiological trait.

There is such a thing as being colorblind and not being able to take in great art that’s in colors and at lesser levels, there are also limits in the ability of people to do this stuff. It’s like IQ, which runs from low to high. Spirituality and IQ are both traits that run low to high and everyone varies in those abilities.

DN: How did your materialist and secularist worldview begin to wobble?

CM: It was basically a decade before I had this series of nudges that moved me off my assumptions.

One of them was simply the question: “Why is there something rather than nothing?” It struck me when my late friend Charles Krauthammer, a columnist, framed the question like that.

And there is no answer that I could come up with that did not come down to the fact that there had to be a creator. That was a big step. The big road-to-Damascus moment wasn’t spiritual, but it was when I read about the anthropic principle that the chances that the universe we live in that enables life to exist are one in trillions.

At the moment of the Big Bang, there are a whole bunch of settings, as if they were settings on a board. And if any of those settings had been tweaked a little bit the other direction, we would live in a universe of black holes and radiation, but no stars and galaxies and life would never have been able to exist.

Do I believe in a one in a trillion chance? I don’t think that’s a very logical way of thinking. The parsimonious, simple answer is — the universe had an intention behind it. And once you say that all at once, a whole variety of doors open up that previously you hadn’t considered.

DN: C.S. Lewis’ writing played a huge role in the evolution of your beliefs. What insights in particular helped you shift away from agnosticism and toward Christianity?

CM: The main one was the idea of a moral law — the way that God reveals himself to us is by nudging us to behave in certain ways. It has stuck with me. I am a big believer in the validity of evolutionary psychology and behavior that are evolutionarily driven, but the phenomenon known as agape in Greek — a kind of selfless love whereby people behave altruistically toward strangers, toward people to whom they have no previous relationship, including putting their own lives at risk. I don’t see how that is produced by evolution.

I don’t see any mechanism for that. I recognize C.S. Lewis’s argument that a lot of times we feel a command to behave in certain ways where our instincts would lead us to behave otherwise.

I actually had one experience of that, where I felt this voice saying, you have no choice but to do such and such. Can I come up with other explanations for that in the way that I was raised or the era I was raised in? Yeah, I can, but I’m not persuaded they are correct. It really had the feeling of a command that I had to do something.

DN: Even after analyzing all the evidence for belief, it still seems that quite a bit of mystery remains. How do you navigate the questions that require faith without full understanding?

CM: The word “mystery” is correct. You do not get to the final destination through the route I took. And the reason you don’t is because at the core of it all is mystery and you have to accept that. And one of the advantages that people like my wife have is that I think they can contemplate that mystery much more profitably than I can.

In the book, I’m giving my fellow companions among the spiritually deprived a way in which they can explore these issues, because the way that is the best way, which is going directly to the mystery, is closed to us. So we do what we can with the skills that we have.

I write that sometimes I feel like a little boy whose nose is pressed against the glass window, watching a party on the other side that I can’t join. My wife is inside, on the other side of the party. But I have gained a lot of ground with the way I’ve approached it.

DN: How do you make the logical or scientific case for the Resurrection?

CM: The Resurrection is a very implausible event. It turns out to be much harder to explain than most nonbelievers think. We know historically that something absolutely weird happened on Easter morning and we know that because we have a set of disciples — who were not strategists, they were not thinking in terms of PR — they were devoted to this leader, who then suffers a completely humiliating, gruesome and painful death. Within a matter of weeks after that, they are energized, completely confident of Jesus being resurrected.

Tell me how that works using ordinary human psychology. And I say: It does not work unless there is something that occurred that had extraordinary power. If they were visions, they would have to be very, very vivid visions that could persuade others that didn’t share them.

You walk away from the scholarship on the Resurrection and you have to say something very close to a miracle happened, at least.

You add the science behind the Shroud of Turin to it — we can’t even come up with any plausible way in which that image was forged. So, along with other evidence, that pushes me very close to saying: the physical resurrection may be reality.

DN: How does that make you feel? Is it strange to admit to yourself that you are believing something that you used to think was a crazy idea?

That’s the right word — it makes me feel very strange. I’m so temperamentally and intellectually resistant to the leap of faith — resistant to giving up my independent judgment and saying, “I believe and I have faith.”

I am not saying I am being right in my resistance to faith. I am saying that for whatever reasons so far, that has been closed off to me.

I also feel like it’s cheating for me to ask for absolute positive physical proof of the Resurrection, because I kind of believe that the leap of faith is an important part of the process. So I am, as they say, conflicted in all of this.

I have problems with faith that I can’t seem to overcome, but I don’t have problems with coming to beliefs that I can’t fully express and that I can’t fully defend.

And at this point we have a very slender semantic difference between that and faith.

DN: Do you think your view of yourself as someone incapable of spiritual experiences makes you less likely to seek or recognize them?

CM: That’s a possibility. Perhaps, I should be more open. It’s like saying that I should have an IQ that’s 10 points higher. I would like that — you tell me how to do it.

I would like to be able to fully enter into music, but I can’t do it. So, on the one hand, I can say you must be open to these experiences. And on an intellectual level, I am. I’m not going to push away the insight I need. But I have problems putting myself in a frame of mind, where I am as open to them as people who have greater, spiritual perception than I have. I just accept that as the way the world is, or the way I am.

I said that one time I had an experience where I felt I had a command to behave in a certain way that came from outside myself. And that had a big impression on me. And I think I need one more. I am one revelation away from taking the rest of the steps.

I’m afraid if I experience it, it is probably going to be because of a tragedy, which is to say I have lived to the age of 82 without ever having had something that put me in the depths of despair. My parents both lived into their late 90s. My sisters are both alive, I’ve never had any serious health crises.

I think a lot of times it’s in the depths of despair that people find God. I think that that’s the kind of emotional openness you need.

DN: What is the most significant byproduct of going through life as a believing person?

I’m getting old and I’m not afraid of death. And that is a change from my 40s, when I would occasionally, as people do, suddenly confront the reality of your eventual death and become filled with dread. I haven’t had those feelings for a long time. And part of it is, I think, the chances of an afterlife are greater than 50%. Sorry, I’m a statistician.

Another reason not to be so afraid of death is even if you aren’t that specific, the whole idea that the universe is undergirded by love in the agape sense, and that grace and forgiveness are real — those ideas by themselves are very comforting.