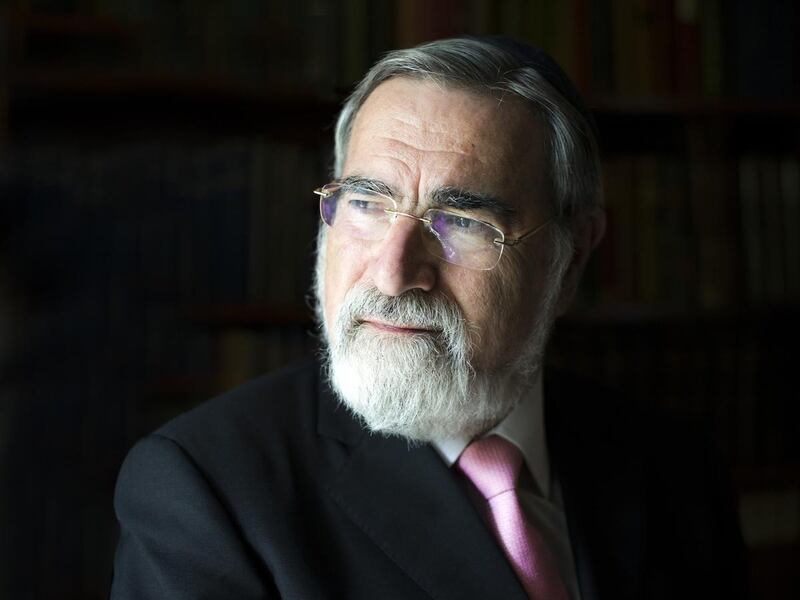

Nine years ago, I sat at the American Enterprise Institute’s Irving Kristol Dinner and found myself directly in front of Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks.

I remember resting my hands on the white tablecloth, the low murmur of conversation around me, the gentle glow of ballroom light on polished silver. And then he rose to speak — and the room changed.

The quiet that fell was not imposed; it was chosen. People leaned forward. Forks paused midair. A reverent stillness settled, as if the crowd sensed that what was about to be said would not simply fill the room, but remain long after it emptied.

He began with grace and humor, but soon his voice turned serious.

“Friends,” he said, “these are really tempestuous times.”

And with that gentle understatement, he opened a moral reckoning. He spoke of “the emergence of what I call a politics of anger,” “the culture of competitive victimhood,” and “the silencing of free speech in our universities.”

He named what many of us felt but struggled to articulate: that something deeper than politics was giving way, that the moral scaffolding of society itself was weakening — a reality that feels even more acute today, as loneliness grows, trust erodes, and belonging thins into performance.

Yet what followed was not despair. It was diagnosis grounded in faith and hope anchored in responsibility. He led us into the Hebrew Bible and into a truth older than any modern ideology: that there exists a profound difference between contract and covenant. “And to put it as simply as I can,” he said, “the social contract creates a state but the social covenant creates a society.”

“A covenant isn’t about me,” he continued. “It’s about us. A covenant isn’t about interests. It’s about identity.”

In that distinction lay the heartbeat of his message and, I realized, the quiet crisis of our age.

He spoke of markets and states, reminding us that “the market is about the creation and distribution of wealth. The state is about the creation and distribution of power.”

But covenant concerns something holier still: “the bonds of belonging and of collective responsibility.” And then came the plea that settled over the room like a prayer: “Don’t lose the American covenant. It’s the most precious thing you have. Renew it now before it’s too late.”

When he said it, there was silence — not the silence of discomfort, but of recognition. And in that silence, I felt something shift. I had already been observing the rise of curated life, the glossy performance of affluence, the seductive glamour of what I have called wealth porn — the transformation of life into spectacle.

But sitting there, hearing him plead for covenant, I understood the deeper truth beneath the surface: we had not only mistaken luxury for meaning, but performance for belonging. We were broadcasting ourselves endlessly and binding ourselves to almost nothing. Rabbi Sacks named the cost of that drift.

“In America, the social contract is still there,” he warned, “but the social covenant is being lost.” Strong families, shared narratives, communal bonds, the sense of e pluribus unum — all were giving way to smaller identities, emotivism, grievance, and fragmentation.

“Instead of a culture of freedom and responsibility,” he observed, “we have a culture of grievances that are always someone else’s responsibility.” And yet, he still believed — fiercely and faithfully — that renewal was possible.

“We need a culture of responsibility, not one of victimhood,” he said, “because if you define yourself as a victim, you can never be free.”

And in words as bracing as they were necessary: “Earned self-respect counts for more than unearned self-esteem.”

Rabbi Sacks, a celebrated moral thinker, died of cancer Nov. 7, 2020, at age 72.

The night I sat across the table from him changed how I understood community. After it, I could no longer see belonging as optional or peripheral. It became sacred.

The family table, the shared prayer, the congregation, the story passed down; these were not nostalgic gestures, but the architecture of freedom itself.

And now, each fall, as the first signs of the holiday season begin to appear, I return to his words again — not as sentiment, but as grounding — letting them steady my moral compass and mark the beginning of a season meant not for spectacle, but for renewal.

And that return is not merely reflective. It has become quietly directive. It reminds me to pick up the phone instead of scrolling past silence, to show up where it would be easier to withdraw, to soften when irritation tempts urgency, to repair rather than retreat, and to remember that covenant is not declared once but practiced daily — in patience, in presence, in the steady humility of tending relationships that do not trend, but endure.

Rabbi Sacks did not simply teach me how to think; he reshaped how I try, imperfectly, to live.The holidays are not merely a pause or a performance. They are a summons.

They call us back to what Rabbi Sacks so beautifully named: the slow and sacred work of binding ourselves again to one another. This season invites us to move, even briefly, away from grievance, distraction, and display — and toward gratitude, presence, responsibility, and faith.

As candles are lit and tables filled, as prayers are whispered and stories retold, the lesson becomes clear. We are being asked not simply to display joy, but to deepen it. Not to curate memory, but to create it. Not to perform belonging, but to live it.

These holidays do not merely commemorate light; they teach us how to carry it — into divided conversations, into strained families, into a civic culture starved for meaning, and into a world that has forgotten how to bind itself to anything lasting.

Rabbi Sacks understood that America, at its best, is a covenantal nation — sustained not only by laws but by loyalty, not only by rights but by responsibilities. He reminded us that “the state exists to serve the people. The people don’t exist to serve the state.”

That distinction remains central to our moral survival. It places limits on power and elevates the sacred institutions — family, faith, community — that make liberty possible.

His final appeal that night did not sound like rhetoric. It sounded like a blessing and a charge. He asked us, as an outsider from the United Kingdom who loved this nation deeply, not to lose what mattered most.

And in that moment, it felt combatingwas entrusting the covenant to us anew.

In a world that urges us to be seen, he called us to be bound.In a culture that promises everything, he asked us to serve.

In an age startled by its own loneliness, he summoned us home.

And perhaps that is the lesson for today and for these holidays: that even in tempestuous times, the path forward is not found in outrage or withdrawal, but in recommitment — to God, to one another, to the quiet disciplines of duty and love, and to the covenant that asks something of us even when selfishness is easier.

Nations are not saved by contracts alone, but by commitments kept, stories honored, families strengthened, and moral courage renewed. And in the soft glow of winter light — against the cold and clamor of our age — Rabbi Sacks’ voice still echoes, reminding us that belonging is not a performance, but a promise.

May we not merely remember the covenant — but live as people who know they are bound by it.

This is the work of the season.This is the inheritance we are asked to honor.

And this is how we keep the fire alive.