WASHINGTON — In his closing remarks Friday, Rep. Adam Schiff invited senators to let Supreme Court Justice John Roberts decide the contested question of whether top White House aides can testify in the impeachment trial of President Donald Trump,

“To the degree that there were a dispute over whether privilege applied, we have a perfectly good judge sitting behind me empowered by the rules of this body to resolve those disputes,” the California Democrat said, responding to resistance that it’s too late to litigate claims of executive privilege.

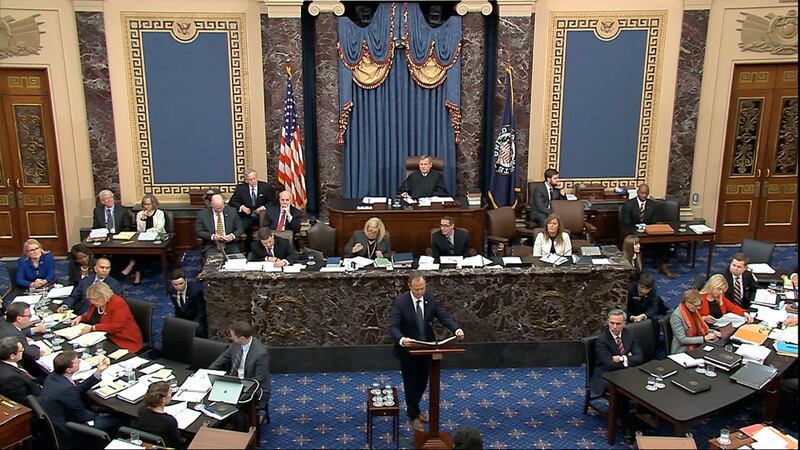

The suggestion to take advantage of having the nation’s top jurist presiding over the trial raises the question of what exactly is the role of the chief justice during a presidential impeachment trial, beyond calling to order and adjourning the proceedings, and occasionally admonishing attorneys to keep it civil — which Roberts did Tuesday.

And other comments by House managers prosecuting the case and Trump’s defense team raised other questions that could play this week in the historic trial on charges that the president abused his power in dealings with Ukraine and obstructed Congress during the investigation by House Democrats.

What is the chief justice’s role?

Under the Constitution, the chief justice of the Supreme Court is to preside over an impeachment trial of a U.S. president. And Schiff reminded the senators that under their rules governing the trial the chief justice can resolve disputes that come up during the trial.

“How often do you get the chance to overrule a chief justice of the Supreme Court? You have to admit it’s every legislator’s dream.” — Rep. Adam Schiff

That has happened in the two other presidential impeachments in American history. During the 1868 trial against President Andrew Johnson, Chief Justice Salmon Chase cast two tie-breaking votes on procedural matters. And during the 1999 trial against President Bill Clinton, Chief Justice William Rehnquist sided with a senator who unexpectedly objected to House managers calling him a juror.

“The Senate is not simply a jury; it is a court in this case,” Rehnquist ruled. “Therefore, counsel should refrain from referring to the senators as jurors,” according to journalist Peter Baker’s account of the trial in “The Breach.”

And if senators feared a decision by Roberts on witnesses would not align with their views, Schiff reminded them the rules allow them to overturn it by a majority vote.

“How often do you get the chance to overrule a chief justice of the Supreme Court?” Schiff asked, eliciting chuckles in a rare light moment in the trial. “You have to admit it’s every legislator’s dream.”

But it’s unlikely that will be an incentive for senators when they vote later this week on whether to subpoena additional witnesses and documents before rendering their verdict. Democrats want to hear from top White House aides who defied subpoenas during the impeachment inquiry, while Trump and most Republicans want a swift trial that could be prolonged by admitting additional evidence.

Questioning by senators

Before voting on the controversial issue of witnesses, senators will have a 16-hour window to ask questions of both the House managers and the White House defense team.

But don’t expect a raucous spectacle of senators personally grilling the attorneys they disagree with. Senators aren’t allowed to speak during the trial and the rules governing the questions ensure they keep quiet.

Senators will submit their written questions to the chief justice who reads them to the attorneys they are directed to. The process is not just orderly, but also orchestrated in a way that senators can work with legal counsel to make sure their side of the story is told.

Wyoming Republican Sen. John Barrasso explained to reporters Friday how the GOP conference will handle questions:

“We will meet as a conference and decide what questions we want to pose and what the order may be of those questions. It seems like the chief justice is going to go back and forth, one Republican question, one Democrat question. And some questions may be to just bring out more information from the White House counsel and some may be specifically to go after what the House” managers have said.

Can a convicted president run again?

Both sides have framed their cases around the upcoming election. House managers accuse Trump of pressuring Ukraine to conduct politically-motivated investigations that would interfere with the 2020 election. And White House counsel said Saturday that Democrats are asking senators to remove Trump from the November ballot.

To be sure, both articles of impeachment approved by the House last month say the charges warrant removal from office “and disqualification to hold and enjoy any office of honor, trust, or profit under the United States.”

It would take a two-thirds vote to convict Trump and make him the first president to be removed from office and disqualified to seek public office again. And no one predicts the GOP-controlled Senate will let that happen.

But should the unlikely take place, there are scenarios where Trump could run for a second term.

Scholars say it’s up to Senate whether to allow someone they find guilty to hold public office again. The chamber would need to decided whether to hold separate votes on removal and disqualification to run again, Stephen M, Griffin, a Tulane University law professor, told Politifact.

Michael J. Gerhardt, a constitutional law professor at the University of North Carolina, wrote that when separate votes have happened in the case of federal judges, the Senate required a two-thirds vote to remove and a simple majority to disqualify.

In 1989 when the Senate removed federal Judge Alcee L. Hastings for soliciting a bribe, but took no vote on disqualification. Hastings ran for Congress three years later and is in his 14th term.

And in the case of President Richard Nixon, the articles of impeachment approved by the House Judiciary Committee didn’t mention disqualification. But that became moot after Nixon resigned before the House impeachment vote.

In the unlikely event that Trump is removed from office but not disqualified to hold elective office, he could remain on his party’s ticket. Vice President Mike Pence, who would be president, would only need to step aside and let Trump be the nominee, according to Politifact. If the GOP won’t have him. he could theoretically run a third-party campaign.