SALT LAKE CITY — In 2019, the population of the United States dropped to its lowest level in the past century, according to newly released estimates from the U.S. Census Bureau.

While the trend can be partly explained by declining fertility rates and rising death rates, lower immigration numbers were also an important factor, according to the Bureau. This comes at a time when the Trump administration has ramped up efforts to reduce the number of immigrants entering the United States.

Does the decline show that Trump administration policies are effectively reducing immigration? And if the trend continues, how could lower immigration numbers affect the U.S. economy?

Lower immigration numbers

In the final year of the Obama administration, 1,046,709 people moved to the United States from other parts of the world — the decade’s highest annual total, NPR reported.

Since then, immigration numbers have steadily declined to 595,348 immigrants in 2019 — the lowest annual total thus far in the Trump administration.

In part, the reduced immigration numbers can be attributed not to specific policies but to long-term economic and demographic trends, according to Randy Capps, demographer and director of U.S. research for the Migration Policy Institute, a nonpartisan think tank based in Washington, D.C.

During the past decade, there was a sharp decrease in the number of Mexicans entering the United States without authorization. Between 2007 and 2016, Mexican-unauthorized immigration declined by 1.5 million, according to a study by the Pew Research Center. This nosedive in Mexican migration was tied to the 2008 recession, which wiped out millions of jobs that attracted undocumented immigrants to the United States, said Capps. And at the same time, the Mexican economy improved, reducing the drive for many migrants to leave their home country in search of work.

In fact, more Mexicans returned to their home country between 2009-2014 than entered the United States, a historic shift, according to a 2015 Pew study.

“For the last few decades, the most common origin country of immigrants has been Mexico, contributing a lot of both legal and unauthorized immigrants,” said Capps. “One of the big drivers in the downward trend in international migration to the U.S. has been that Mexico is not contributing as many migrants as it once was.”

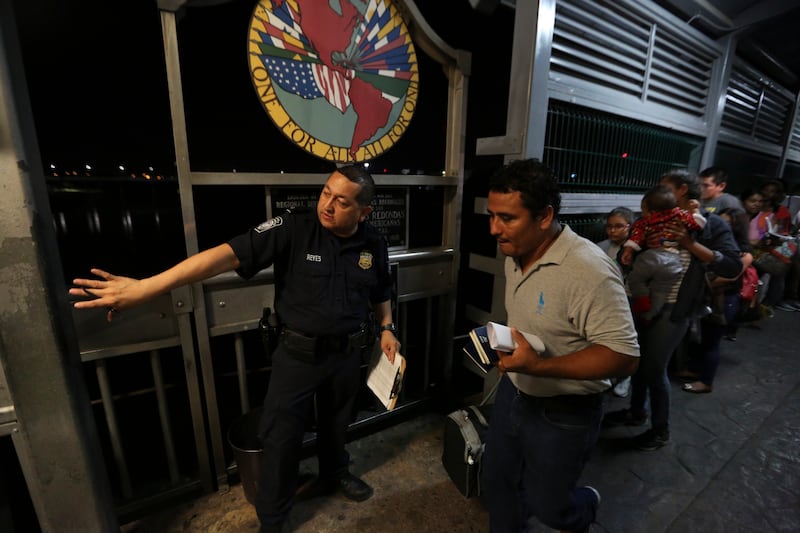

At the same time, Central American immigration to the United States has been on the upswing, with a surge in people from El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras traveling through Mexico to seek asylum in the United States. The number of unauthorized immigrants from Central America increased by 375,000 between 2007-2016, according to Pew.

But recent Trump administration policies have been an important impact factor in reducing the number of immigrants coming to the U.S. both legally and illegally, said Capps.

The Trump administration has slashed the number of refugees admitted to the U.S. to historic lows and has proposed restrictions on green cards and family-based migration. Trump has also tried to restrict Central American asylum-seekers from entering the country, with proposals such as “Remain in Mexico,” which bars asylum-seekers from waiting in the United States while their asylum applications are processed.

“The Trump administration has had mixed success,” said Capps. “They were successful in dramatically reducing the size of the refugee program. But so far, they haven’t really reduced legal immigration overall by very much, and I think it’ll be hard for them to do that without Congress’ support.”

Economic impact

A reduction in the number of immigrants coming to the United States — both legally and illegally — could have significant implications for the U.S. economy, said William Frey, a demographer and senior fellow at The Brookings Institution.

Specifically, as fertility rates in the U.S. continue to decline and baby boomers age out of the workforce, the U.S. will need to address the problem of workers missing from the labor force, he said. Immigration will be a “safety valve” in helping bolster both labor force growth and population growth in an aging society, he said.

“I think it’s important for our policymakers to think carefully about immigration,” he said. “There’s a lot of rhetoric about immigrants taking jobs from Americans, but not a lot of thorough examination of what immigration will mean for the economy and the country moving forward.”

The U.S. labor force economy is already seeing the impacts of lower immigration numbers, said Capps. On the one hand, he said, the decrease in the number of foreign-born workers has benefited American-born workers, with labor shortages and increased competition resulting in decreased unemployment and higher wages for some workers.

On the other hand, the labor shortages in some industries, such as agriculture and seasonal recreation, have hurt some local economies. And some industries have increasingly embraced automation or have turned to outsourcing as a way to cope with labor shortages, said Capps, solutions that don’t benefit American workers directly.

Both Capps and Frey said that they expect immigration numbers to rebound in future years, fueled by changes in global migration patterns, spurred by conflicts or economic changes in countries around the world. The biggest sources of migration moving forward are likely to be from Asia, the Middle East and Africa, said Capps.

But Capps said U.S. policy will play an important role in how many immigrants are admitted to the United States. In Capps’ view, America needs to change its immigration system to allow it to be more flexible and responsive to the needs of the U.S. economy.

“We need to rethink our immigration system and make it much more workforce oriented,” he said. “The data shows us that we are really going to need more immigrant workers, but we want to get the ones who fit our labor market best without harming U.S. workers. We need a flexible system that doesn’t just have set ceilings and categories, but where the numbers can rise when there’s more demand for workers and fall when there’s less demand.”