In 1893, an English professor from Massachusetts was so inspired by the mountain views in Colorado that she penned what would become one of America’s most famous hymns.

In her poem, Katharine Lee Bates expressed awe for the spacious sky, purple mountains and fruited plain, and said of her country, “God shed his grace on thee.”

Repeated twice in “America the Beautiful,” the line is a poetic summary of a longstanding belief among many Americans: that the nation was uniquely blessed by God and has a special role in human history. But the number of Americans who believe this has sharply declined in recent years.

A new poll from the Public Religion Research Institute found that, for the first time since the nonpartisan organization began asking the question in 2011, a majority of Americans say they disagree with the statement “God has granted America a special role in human history.”

According to the 2020 American Values Survey, 40% percent of Americans agreed with that statement, while 58% disagree. And, “Notably, the share of Americans who completely disagree (40%) has nearly doubled since the question was last asked, in the lead-up to the 2016 election (22%),” the report said.

Among other findings, 62% of Americans say their country is not currently or never has been a Christian nation, and only one-quarter believe that the U.S. is a good moral example to the rest of the world. And the number of people who say you need to believe in God to be a moral person has fallen by 10 percentage points in four years, from 49% to 39%.

While the poll shows a significant partisan divide on the question of whether the U.S. has a special place in the world, it’s a view that has been expressed by both Democrat and Republican presidents, including John F. Kennedy, Ronald Reagan and Barack Obama, said Abram Van Engen, an associate professor at Washington University in St. Louis and author of “City on a Hill: A History of American Exceptionalism.”

Van Engen and other analysts point to three reasons that Americans are less likely to see their country as special, compared to years past.

A ‘sizable’ decline

At a panel discussion about the survey hosted by the Brookings Institution, Karlyn Bowman of the American Enterprise Institute said the findings reminded her of an essay by the late sociologist Dan Yankelovich, who said that Americans start with their values when they make up their minds about an issue.

Those values are less likely to stem from organized religion, according to research that shows the rise of the “religious nones,” people who consider themselves spiritual but don’t affiliate with an organized religion.

Andra Gillespie, associate professor of political science and director of the James Weldon Johnson Institute at Emory University, believes the decline in people who believe God ordained America for a special purpose is largely due to the increase in the religious nones, who make up about a quarter of the population.

“Disagreement with that question is largely driven by non-religiously affiliated respondents, who overwhelmingly reject the idea. Seventy-three percent completely disagree (with the statement),” she said.

But there is also a significant partisan divide.

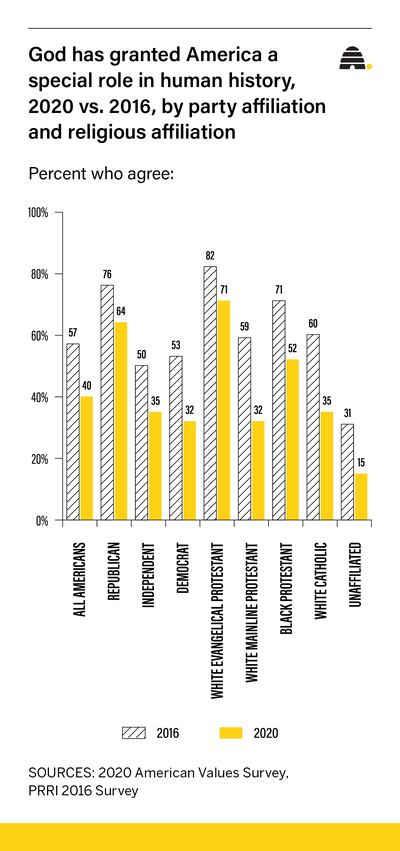

Nearly two-thirds of Republicans say God has granted the U.S. a special role in human history, compared to about half as many independents (35%) and Democrats (32%), the report said.

Six in 10 independents and 67% of Democrats disagreed with the statement.

Natalie Jackson, research director for the Public Religion Research Institute, noted the number of people who believe in America’s specialness has declined across all groups, even Republicans, in recent years.

In 2016, 76% of Republicans agreed with the statement, compared to 64% now. But it was the drop among all Americans that was most striking to the researchers: 17 points within the span of four years.

“The drop-off to 40% (overall) now is really sizable, and I think that reflects a lot of the general pessimism we see about the state of the country today,” Jackson said. “People do believe our best days our ahead of us, but they also believe that where we are right now is not good. I think you see that factor in when you ask a question like this.”

Bowman also said that the pandemic likely plays into the negative answers.

“If you thought God granted America a special place, you might have thought we would have been spared, in some particular way. It didn’t happen,” Bowman said.

Jackson agreed, saying that people tend to consider their personal circumstances when answering questions like this. “It can be difficult to square the concept of a widespread pandemic — particularly if you’re aware that the U.S. is in a worse state than a lot of other countries — with the idea that this country has a special role in human history.”

Similarly, a decline in the number of Black Americans agreeing with the statement might be related to incidents of racial injustice this year, she said.

A city in danger?

Van Engen, who conducts research on the use of the phrase “city on a hill” with regard to America, said there could be another reason for the decline in belief that America serves a special, God-ordained purpose in history: the lack of an atheistic adversary.

“The ‘city on the hill’ is really a Cold War creation,” he said.

The phrase itself comes from the Sermon of the Mount in the Bible’s gospel of Matthew, in which Jesus told his followers, “Ye are the light of the world. A city that is set on a hill cannot be hid.”

The earliest known use of the phrase in America was in a sermon by a Puritan minister, most likely in 1630, that got little attention at the time, Van Engen said. Two hundred years later, a single copy of the sermon was found in New York’s historical archives and returned to Massachusetts. It didn’t get much attention, however, until a Harvard scholar wrote about it in the 1940s, saying the sermon “set the purpose and identity of America.”

Then, in 1961, John F. Kennedy used the phrase in a speech, and later, Ronald Reagan did, as well. After that, in the American lexicon, “‘city on a hill’ starts referring to the nation and not the church,” Van Engen said. “You can chart the way the nation takes over the language of the church.”

Van Engen said he believes the phrase, and America’s sense of itself as a “sanctified country,” lost some of its power after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

“The Cold War sets up this stark binary between an official atheist country against a country that was officially democratic and unofficially religious — not established, but understood as Christian” he said. He noted that church attendance was highest in the U.S. in the 1950s, and that “one nation under God” was added to the Pledge of Allegiance in 1954.

“We become a nation of God more so during the Cold War because of squaring off against an atheist enemy,” Van Engen said. “If you don’t have an official atheist enemy that everyone’s united against, then you don’t need the religious rhetoric that unites you against that enemy.”

A fault line of faith

David McCullough Jr., a high school history teacher in Wellesley, Massachusetts, went viral in 2012 when he told students at a commencement ceremony “You are not special.”

McCullough later developed the speech into a book, in which he encourages people, especially parents and young adults, to leave the “cult of exceptionalism” for imperfect but ultimately more satisfying lives.

In an email, McCullough noted that the survey question presupposes belief in God, “and a particular God at that,” which may make people less likely to answer in the affirmative in a time of increasing secularization.

“Also, whether we’re talking about a nation or an individual, thinking oneself special is risky under any pretext if one respects and hopes to get along with others,” McCullough said.

The Public Religion Research Institute survey did not distinguish between atheists and agnostics and people who are unaffiliated. But it showed a gap between white Protestants and other people of faith.

White evangelical Protestants are most likely to believe America has a special role in history (71%, down from 82% in 2016). Black Protestants follow, at 52%, down from 71% four years ago. White mainline Protestants look roughly the same as Catholics on this question: 32% and 35% respectively. Just 15% of people unaffiliated with a faith group say America has a special role in history.

Of all the groups surveyed, Republicans are the least likely to have changed their beliefs in recent years, Jackson said, a finding that is consistent with the conservative values that many Republicans profess. A key component of conservatism is belief in fixed, eternal values.

The findings show yet another fault line separating Americans, even among those who profess the same faith, and makes clear that Republicans and Democrats are different in ways beyond policy, Jackson said.

“It tells the story of how the two parties are dividing in a different way,” she said. “The results on these questions really pick up how different the parties are religiously.”