A few days after the election, the Rev. Salvatore Sapienza struggled to plan his Sunday sermon. Political tensions were running high and he felt a need to speak to the moment. But, he also didn’t want to alienate the red minority in the predominantly blue United Church of Christ he leads in Douglas, Michigan.

He wanted to keep his congregation’s sights on the thing that brings them together: God.

So he crafted a message that was at once nonpartisan, but also political and then closed the service with a unity prayer.

“What I decided to do, I said that no matter who is elected, our role as the Christian church remains the same — no matter the outcome of this election or any election the role of church remains the same,” says the Rev. Sapienza. “It’s my goal to get the people in my congregation with opposing viewpoints to come together.”

But coming together doesn’t necessarily mean that congregants need to agree with one another.

While many pastors avoid tackling a partisan divide head on for fear of exacerbating tensions, others say that such tensions should be expected and can be opportunities to teach Christian principles loving those you disagree with and finding common ground.

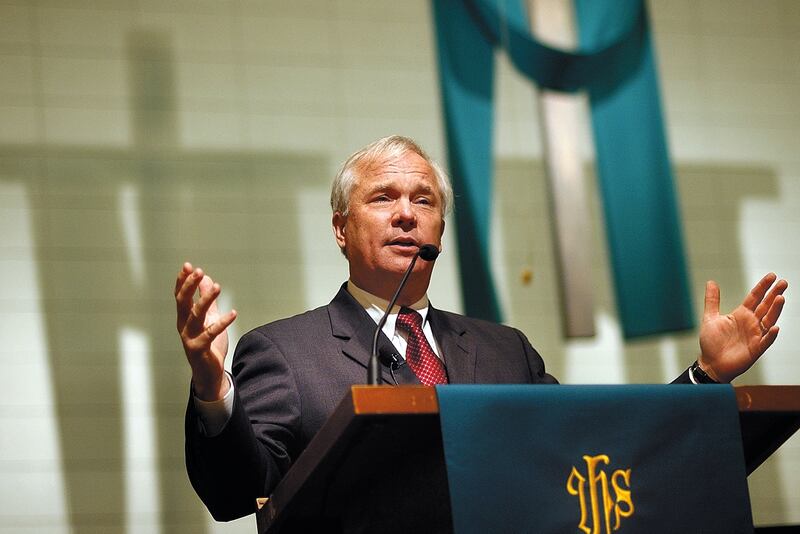

“I remember being in a conversation about the political divide a couple of years ago,” said the Rev. Dr. William Willimon, professor of the practice of christian ministry at Duke Divinity School and a retired United Methodist Church bishop, “and someone saying, ‘If you say that your church is unified then you haven’t done a very good job of evangelism — all you’ve done is collect people with politics in common and what you need is people who have God in common.’”

‘Unity is a rare thing’

Some pastors instinctively view conflict within their congregations as a failure of leadership and a threat to their job, divinity faculty told the Deseret News.

“I think pastors tend to overemphasize or worry greatly about divisions in their congregations,” said the Rev. Willimon. “In one sense, that’s appropriate and yet you can see that congregational unity is a rare thing.”

He teaches that divisions are “the norm … so the issue becomes how can we live together in the church, in this congregation?”

He adds that divisions can also be the sign of a thriving ministry. “I tell pastors, ‘The fact that you have a politically divided congregation isn’t a sign you made a mistake. It can be a sign that you’ve done a really good job gathering people.’”

So, “conflict should be managed not avoided,” he says.

And that takes courage, says Amy Black, a political science professor at Wheaton College, an evangelical liberal arts school in Illinois. “If a pastor serves a politically divided congregation, even if you say something as straightforward as ‘Love your enemy,’ you’re going to take the risk of people leaving.”

Pastors don’t want to upset members of their churches because they’re dependent on their congregants’ continued support to make a living. If a member is offended by the way the pastor handles politics and divisions, they can just leave and pick a church that better suits their tastes — or politics.

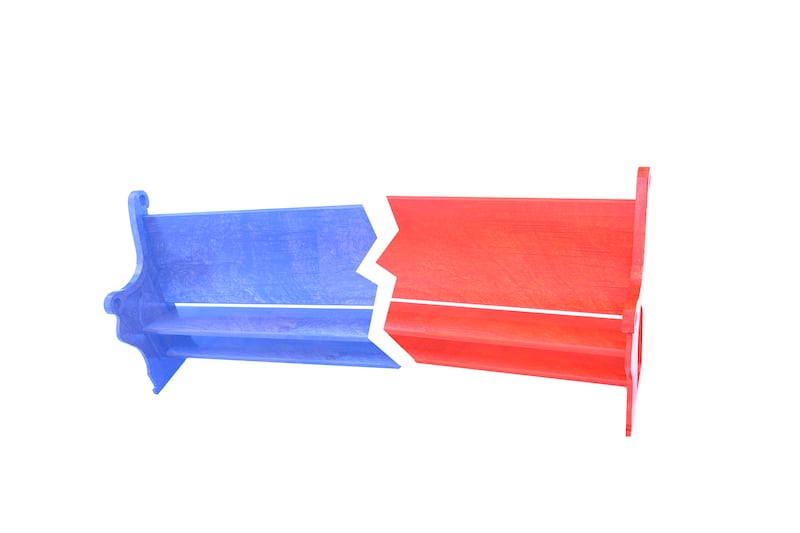

Referencing the “big sort,” a term attributed to journalist Bill Bishop and popularized by his book by the same name, Black says many Americans move to cities and neighborhoods based on the prevailing politics of the place — which helps to create and reinforce red and blue churches.

But when Americans end up in churches full of like-minded people, they’re missing out on a basic practice, says the Rev. Willimon, “One part of being Christian means learning to worship with or praise God with people who you have little in common.”

Picking one’s church based on its politics “is exactly the wrong order for people of faith,” adds Black. “We must first understand the religious principles of our faith and then apply them to politics — not in the reverse order.”

Church leaders, Black says, can do their part by reminding congregations of the most “fundamental tenets of our faith,” including the command to “love our enemies and bless those who persecute you.”

Disagreeing respectfully

Theologians interviewed for this story agree that many pastors are ill-equipped to deal with a partisan divide within a congregation.

“I do think there is a gap in the training,” says Black, explaining that most pastors don’t get this sort of training in divinity school.

Braver Angels is an organization that offers some remedies. Founded in December 2016, in the wake of another divisive election, the organization’s goal is to help Americans “disagree respectfully — and just maybe find common ground,” according to its website.

Approximately 200 pastors have signed up for the organization’s “With Malice Toward None” program, according to Julie Boler, a partnerships specialist at Braver Angels who works closely with religious leaders. In the training, pastors get “depolarization tools and skills that they can take into their churches,” says Boler.

She explains that some of those trainings can also help congregants deal with partisan conflict they experience outside of the church. A workshop called “Depolarizing Within,” Boler says, helps people “confront their own biases and turn down the temperature on their reactions … and bring grace humility, compassion, and love — or at least respect — to the way they think about people who vote differently than them or have opposing political viewpoints.”

Those who attend Braver Angels’ workshops become a “positive social contagion,” he explains. “Their friends might be so polarized that he or she might not show up at a workshop but they will take it to their peers.”

The Rev. Greg Boyd, pastor of Woodland Hills Church in St. Paul, Minnesota, partnered with Braver Angels in the lead up to the election to offer his congregation a four-part series addressing political divisions.

“The partisan divide is always going to be there,” he reflects, adding that it’s part of democracy. “But it doesn’t have to be bitter and acrimonious and hateful and suspicious.”

The Rev. Boyd faults the echo chambers of social media for fomenting intolerance and making it difficult to accept others they disagree with as human beings.

Last week, President Russell M. Nelson of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints encouraged members worldwide to counter rancor that is rife on social media by turning their feeds into a “gratitude journal.”

A physician by training, President Nelson said expressing gratitude can be therapeutic and healing for the anxiety and hard feelings that have surfaced in 2020 in the wake of a pandemic, racial unrest and an election.

Black also sees value in the area of volunteer service. She offers the example of Warnerville, Illinois, where “a coalition of local churches work together primarily on service related projects.”

“We can serve our community better as a group rather than individual churches,” Black says. “We have differences and we come across those differences to serve … you’re putting aside certain differences and focusing on what unifies you — that need for service.”

Reading the gospel afresh

While politics can be contentious in predominately white churches, for Black Americans, there is consensus that politics belong in the church.

In both the past and present, “African American pastors and clergy in this county have always had to carry more than just religious truth,” says the Rev. Dwight A. Radcliff Jr., academic dean for the William E. Pannell Center for African American Church Studies at Fuller Theological Seminary.

Historically speaking, Black churches served as everything from publishing houses and educational centers, the Rev. Radcliff explains. Black churches have also fostered generations of Black leadership and politicians.

When he considers the partisan divide that challenges many white congregations, however, Rev. Radcliff has some advice for his fellow pastors. “We’ve got to read the gospel afresh and see Jesus afresh (and) open ourselves up to hearing how Jesus taught and not just what he taught,” he says. “Jesus often centers the marginalized, the unlikely — the good samaritan, a woman sweeping the house — all these little parables that are often denoting the other person.”

The Rev. Willimon says the church can be the best place to address divisive issues — the sorts of topics that might break up a Thanksgiving dinner.

“In church you say, ‘Hello I’m a sinner and you’re a sinner and we’re both related to a savior that saves sinners so that means my position could be wrong it could be tainted with my own sin but yours could be, too,’” he says. “Now, let’s have an argument. Let’s be as passionate as we want and then when we’re done we’re going to go to the Lord’s table together and work in the Lord’s food pantry together.”