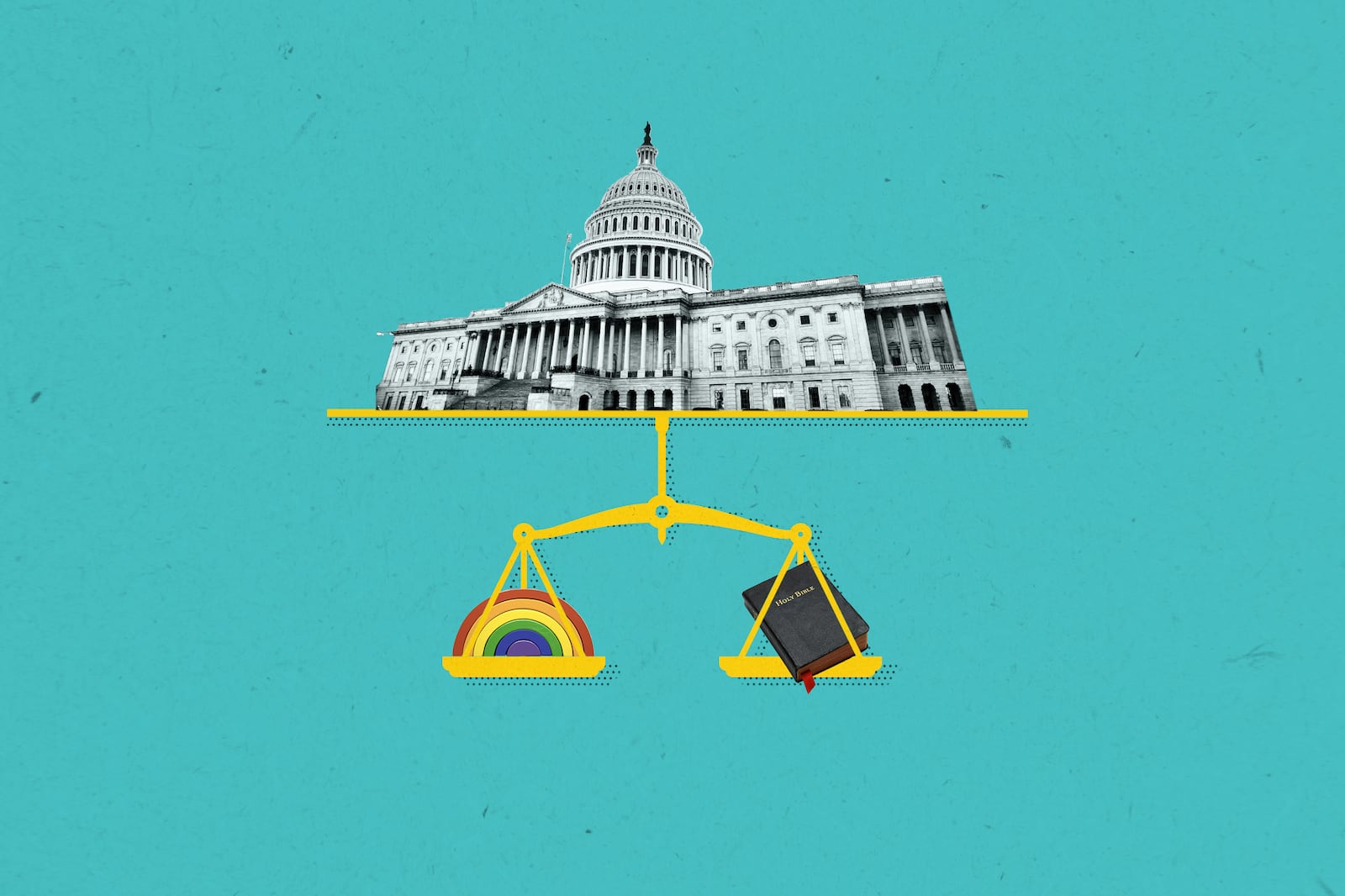

The Fairness for All Act proved it’s possible for a wide range of religious and civil rights groups to come together and write a bill balancing religious freedom with LGBTQ rights.

But it hasn’t yet proved that such a bill can pass Congress.

Since its introduction in the House of Representatives one year ago, the legislation, which would ban discrimination against gay and transgender Americans in many areas of public life while offering new legal protections to people of faith, has stalled in the House Judiciary Committee, among others, and faced criticism from leaders on both sides of the aisle.

Over the same time period, the problems it seeks to address have gotten worse. Members of the LGBTQ community and people of faith increasingly see their careers threatened or family plans complicated due to their beliefs about sexuality, marriage and gender.

“There are really entrenched groups on the fringes of both sides of the political spectrum who are more comfortable fighting about this forever” than discussing legislative solutions, said Tyler Deaton, who is part of the coalition behind the bill.

Resistance from those groups and others has so far hindered the Fairness for All Act’s progress. But the 2020 election gave the bill’s supporters hope that their proposals will soon get a fair shake.

“We’ve got a new president coming in” who supports adding LGBTQ nondiscrimination protections to civil rights law, Deaton said. “That’s going to put more focus than ever on needing to find a federal bill that can pass.”

Although President-elect Joe Biden and congressional Democrats plan to prioritize a competing bill called the Equality Act, the Fairness for All coalition believes policymakers will need to embrace their more balanced approach to religious freedom and LGBTQ rights in order to get something done.

“I think the most viable path forward for any legislative action in the next four years is something fairly close to the Fairness for All Act,” said Tim Schultz, who is president of the 1st Amendment Partnership and served as an adviser for the bill.

Unexpected optimism

The Fairness for All Act grew out of more than three years of dialogue between a diverse group of individuals and organizations concerned with growing legal conflict between religious freedom and LGBTQ rights.

The coalition, which includes the Seventh-day Adventist Church, the National Association of Evangelicals and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, aimed to find a way to address anti-LGBTQ discrimination without jeopardizing faith groups’ ability to live out their beliefs.

“We want to do the right thing by gay rights, but we think you have to do the right thing by religious freedom, too,” said Stanely Carlson-Thies, the founder and senior director of the Institutional Religious Freedom Alliance, to the Deseret News last year.

Although they were excited about their bill, the Fairness for All coalition said from the beginning the road to legislative change would be long and complicated.

They said they’d focus, at least in the short term, on initiating productive conversations, rather than worry about when and if the bill would make it to the president’s desk.

“We wanted to get people on the record, people known as supporters of religious freedom or gay rights, about their interests” and what this bill had to offer to them, Schultz said.

But even this modest goal seemed out of reach when the Fairness for All Act was first introduced.

The bill faced criticism from lawmakers on both sides of the aisle and leaders from a variety of religious groups and gay rights organizations, including power players like the ACLU.

“The ‘Fairness for All’ Act is anything but fair, and it certainly does not serve all of us. It is an affront to existing civil rights protections that protect people on the basis of race, sex and religion and creates new, substandard protections for LGBTQ people with massive loopholes and carve-outs,” argued a statement released last year by the ACLU and 14 other civil rights groups.

Other critics argued the bill actually goes too far with its protections for the gay and transgender community, expressing concerns about its potential impact on faith groups.

The Fairness for All Act “would so narrow First Amendment (religious liberty) protections that I must actively oppose it,” said Sen. Mike Lee, R-Utah, in a statement released last year about the bill, which did not have a Senate sponsor when it was first introduced.

To this day, many people on all sides of the issue consider the bill to be a nonstarter. They aren’t ready to compromise on religious freedom or LGBTQ rights, said Deaton, who is a senior adviser to the American Unity Fund, a conservative gay rights advocacy organization.

Some people “would be happy suing each other in the courts forever,” he said.

As a result, political commentators often treat the Fairness for All Act like a pipe dream, Schultz said. He’s gotten used to people assuming that he’s feeling pretty depressed.

“They’ll say something like, ‘It doesn’t look like the Fairness for All Act is going to pass anytime soon. You must be disappointed,’” he said.

In reality, Schultz said he is feeling “pretty good.” Over the past 12 months, he’s met with elected officials interested in finding middle ground in the conflict over gay rights and religious freedom.

“I think there are a lot of Republicans and a lot of Democrats wanting to come to the middle,” he said.

And, if Biden has his way, they may have an opportunity to very soon, Deaton said.

“I think Biden wants to be able to sign comprehensive LGBTQ civil rights into law. He will be able to move (House Speaker Nancy) Pelosi and Senate Leader (Mitch) McConnell toward a resolution. If anyone can, he can,” he said.

Opportunity for change

To be clear, Biden has not expressed support for the Fairness for All Act. Instead, he’s repeatedly praised the Equality Act, which passed the House last year.

“I will make enactment of the Equality Act a top legislative priority during my first 100 days,” Biden said in a recent email interview with gay rights activist Mark Segal.

The Equality Act, like the Fairness for All Act, aims to expand federal civil rights law by adding LGBTQ nondiscrimination protections. However, it would not increase legal protections for faith groups and would, instead, limit how existing religious freedom protections can be applied.

“The Equality Act makes it clear that the Religious Freedom Restoration Act is not something that can be used to create a gaping hole in these federal protections” against LGBTQ discrimination, said Sharon McGowan, the chief strategy officer and legal director of Lambda Legal, to the Deseret News last year.

Biden’s election undoubtedly provided a significant boost to supporters of the Equality Act, Schultz said. But, regardless of how the upcoming runoff races in Georgia turn out, the bill is unlikely to get through the Senate, since 60 votes are needed to avoid a filibuster.

“The Equality Act is never going to pass unless it attracts significant Republican support,” he said.

The Equality Act currently has one Republican sponsor in the Senate: Sen. Susan Collins from Maine. This summer, she and other sponsors of the bill called for it to be brought up for a vote.

“We have a responsibility to reaffirm the principle that harassment and discrimination are not tolerated in our country,” their statement said.

Like Schultz, Deaton believes the Equality Act would need to be adjusted to address at least some of the concerns of religious organizations to pass the Senate. Lawmakers could incorporate some elements of the Fairness for All Act.

The Fairness for All approach to LGBTQ rights and religious freedom offers everyone something to get excited about, said Utah Rep. Chris Stewart, a Republican and sponsor of the Fairness for All Act in the House, in a statement.

“This is a great compromise bill where everyone gets some of what they want. When this bill passes, our LGBTQ brothers and sisters get federal protections outside of the narrow employment protections recognized by the Supreme Court this summer and our religious brothers and sisters get individual religious freedom protections that are not currently guaranteed by federal law,” he said.

Deaton and Schultz are hopeful the Biden administration could come to embrace the Fairness for All Act or something like it.

“The jury is still out as to whether that will happen, but I think the signs so far are good,” Schultz said, highlighting Biden’s outreach to religious conservatives on the campaign trail.

Looking ahead

Despite their optimism, members of the Fairness for All coalition acknowledge that the success of their bill, or an amended Equality Act, depends on more than Biden’s willingness to champion compromise legislation.

Stakeholders like the ACLU and Catholic Church will have to agree to come to the bargaining table. Members of both parties will have to let go of the temptation to wait to take action until they have total control of the White House and Congress.

“Some people don’t want to do anything (regarding LGBTQ rights) until they have unilateral power in Washington, D.C.,” Deaton said.

Advocacy groups will also have to stop relying on the legal system to settle the conflicts that Congress is better suited to address, Deaton added, noting that legislative solutions are more nuanced and comprehensive than court rulings can be.

“The Fairness for All Act is attractive to me as a gay man because I know it answers important questions in ways that have certainty and permanency,” he said. “The court uses a jackhammer. Congress can use a scalpel.”

Although the Supreme Court signaled interest in a Fairness for All-like approach to LGBTQ rights this summer, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s death and Justice Amy Coney Barrett’s confirmation to the court since then makes it less likely for gay or transgender plaintiffs to prevail in cases involving religious freedom protections.

“The Supreme Court has a broad view of the (First Amendment’s) free exercise clause,” Schultz said.

In the year ahead, the Fairness for All Act will be reintroduced in the House and likely introduced for the first time in the Senate. The bill’s supporters will continue to promote the legislation in meetings with lawmakers and other stakeholders in conflict between religious freedom protections and LGBTQ rights.

There’s still plenty of hard work left to do, but spirits are high, Schultz said. He and other members of the Fairness for All coalition remain proud of the bill they produced.

“I don’t want to speak for every individual entity or elected official involved, but I have yet to hear any buyer’s remorse,” Schultz said.

If anything, some are more convinced than ever that they’ve identified the best path to a more peaceful future.

“After a tough year of contentious politics and lockdowns that threaten freedoms, America needs Fairness For All. We need to be fighting for each other’s freedom,” Stewart said.