SALT LAKE CITY — For the past three weeks, Americans have been getting a lesson on how states and the federal government operate in the throes of a crisis.

Those governing the nation’s 50 independent states have been under an intense public spotlight as they’ve taken charge in slowing the spread of the highly contagious and sometimes deadly coronavirus.

Public health and safety is the purview of the states, after all, and a system has evolved where the federal government is poised to assist when natural disasters overwhelm a state’s limited resources. Controlling how the economy responds to unexpected events largely falls under federal authority. But the current pandemic has enveloped every state, creating an unprecedented health and economic crisis that is straining the relationship between the nation’s constitutionally divided state and federal powers.

“You’ve got that mix of public health and the economy that makes the relationship more complicated,” said John Weingart, director of Rutgers University’s Center on the American Governor. “There should be a cooperative relationship. But in the circumstances of a crisis happening for the first time, everyone’s having to feel their way to some extent, even if you assume everybody’s operating with the best of intentions.”

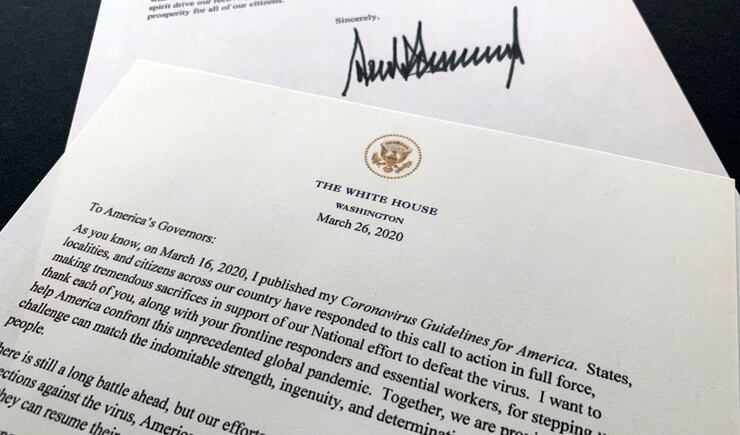

As a result, governors have issued strict directives that often conflicted with President Donald Trump’s upbeat outlook on when life would return to normal for most Americans. It wasn’t until this week that the message from the White House and the nation’s state houses sounded consistent with social distancing guidelines in effect for all of April based on a dire prediction that COVID-19 will claim between 100,000 to 240,000 lives — at the low end.

But the administration has resisted calls for a nationwide stay-at-home order, saying those decisions are up to individual states.

“We trust the governors and the mayors to understand their people and understand whether or not they feel like they can trust the people in their states to make the right decisions,” Surgeon General Jerome Adams said Wednesday on ABC’s “Good Morning America.”

Complicating matters, the pandemic arrived in an election year, with Trump and about a dozen gubernatorial incumbents likely to be judged by how they led and protected their constituencies throughout the outbreak, which is also wreaking havoc on local and national economies.

In the past several weeks, signs have surfaced that partisanship could become an obstacle to saving lives and jobs, with some Democratic governors blasting the federal government’s handling of initial testing for the virus and Trump firing back with personal attacks and a warning that states “have to treat us well” if they want federal help.

“I fear it’s going to get more fraught as the pandemic continues and maybe grows as the election gets closer,” Weingart said. “It’s going to be in the interest of the president and governors to represent that the way they handled this crisis was the right way.”

Federal aid

The Constitution divvies up some duties between the federal and state government, but the drafters agreed to leave it intentionally vague on where federal powers end and state powers begin, legal scholars agree.

But that ill-defined division of power has led to conflict, which has peaked in past decades with increasing federal environmental and business regulation, health care and immigration, said Justin Phillips, a political science professor who focuses on state and local politics at Columbia University.

Federal money, which funds as much as 30%-40% of a state’s annual budget, often comes with strings attached to force compliance with federal regulations, he explained.

“I would describe the relationship between the national government and the states as one of increasing tension,” Phillips said. “And that’s especially true for states where you have a Democratic governor, during a period of a Republican presidential administration, or a Republican governor in a period of a Democratic presidential administration.”

Disasters like floods, drought, earthquakes, extreme weather and wildfires have usually been exceptions to that tension. Over the decades, federal help came piecemeal through legislation or short-lived agencies. But that changed in the 1970s when Congress created what would become the Federal Emergency Management Agency, or FEMA, which has since distributed federal aid to states where the governor has declared a disaster or emergency.

That federal help is critical to states that have balanced budget requirements — every state but Vermont — limiting the resources states have to respond to catastrophic events, Phillips explained.

“The fiscal realities of states are really tough,” he said. “States are going to be really hurting because they will have to spend money dealing with the virus while tax revenues won’t be coming in” as a result of directives to restrict business activity to contain the virus’ spread.

In Utah, where conservative fiscal management has earned the state a AAA bond rating, officials built massive federal emergency aid into their COVID-19 response plan to offset the anticipated health and economic damage caused by the outbreak. Meanwhile, Gov. Gary Herbert is expected to call the Legislature into special session to make adjustments to ensure the state budget balances by July 1.

Play nice

Receiving federal aid during a pandemic, however, isn’t as simple as just asking for it — not when all 50 states need help from a president who’s made it clear he places a premium on “appreciation,” and not just criticism, for what his administration is doing.

The nonpartisan National Governors Association is helping all its members get access to Congress and the White House, said Herbert’s spokeswoman Anna Lehnardt, noting Vice President Mike Pence, a former governor of Indiana, has also made sure states have a seat at the table in the national response to the outbreak.

“So far, the federal government is listening to states and is granting many of their requests, including giving direct aid in the form of block grants,” she said.

Herbert, a Republican, is a past chairman of the National Governors Association.

Phillips said he’s watching how Democratic governors clamor for federal money and help to secure medical equipment for testing and treatment.

“Typically Democrats in Congress have been more willing to give states money in these kind of circumstances, so I think the key will probably be for Republican governors to be as vocal as Democratic governors about needing this kind of assistance” he said.

Several Democratic governors, such as Washington’s Jay Inslee, Michigan’s Gretchen Whitmer and New York’s Andrew Cuomo, have pulled no punches in blaming the administration for a slow response for the spread of the virus or a lack of urgency for shortages of ventilators and other medical supplies. Trump has fired back at governors who’ve attacked him.

There has also been unexpected praise for Trump from California. Gov. Gavin Newsom, a Democrat and reliable critic of the White House, has struck up a collaborative relationship with the president, praising Trump’s response and expressing confidence the administration will assist his state, CNN and other news outlets have reported.

At a recent Fox News town hall, Trump implied that’s what he expects from states if they want federal assistance. “We are doing very well with, I think, almost all of the governors, for the most part,” he said. “But you know, it’s a two-way street. They have to treat us well.”

Trump has had several conference calls with the nation’s governors, some of whom have clashed with him over the federal government’s response while others have “calculated that it will be easier to get the needs of their states fulfilled by praising Mr. Trump, who seeks credit and affirmation in most interactions,” according to The New York Times.

According to a transcript of a March 20 teleconference with governors, Nevada Gov. Steve Sisolak, a Democrat, was among those taking a cautious approach in his request for aid for his state’s beleaguered hospitality industry.

“I’d like to ask one big thing of you. I know that you’re looking at potential recovery packages already in the stimulus. And you talked about the airlines and the cruise ships,” he asked. “I would like you to consider including the hospitality industry in that. I have, unfortunately, had to shut down the Strip in Las Vegas, and tens of thousands of hospitality workers have been displaced as a result of that.”

“I think it’s a great idea ... I think it’s something we’ll be thinking about,” Trump responded. “And thank you, governor.”

Hospitality leaders said the $2 trillion emergency aid package Congress passed last week was “a good start” but more will be needed to prevent restaurants and other businesses from closing their doors permanently, Bloomberg reported.

Political survival

A few hours after Monday’s midday conference call with the governors, Trump held a daily briefing in the White House Rose Garden where he described a sobering outlook resembling that projected earlier by many governors, who have imposed restrictions in their respective states through the month of April.

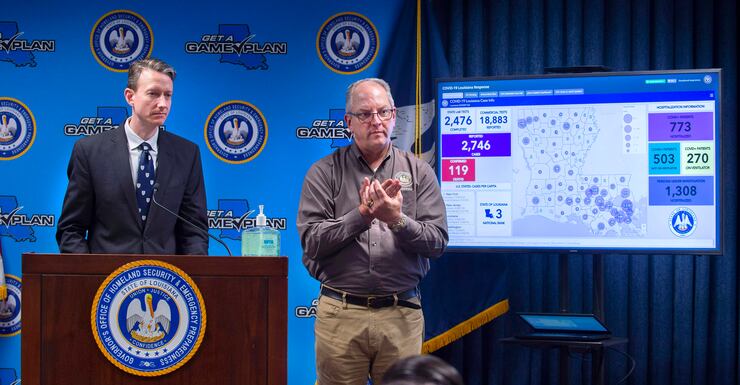

After being briefed by his public health advisers that the coronavirus deaths could number at least 100,000 if people comply with social distancing guidelines, the president didn’t forecast that Americans would soon be safe, but instead announced that the peak in fatalities could happen in two weeks and federal social distancing guidelines would be extended two weeks to April 30.

“Nothing would be worse than declaring victory before the victory is won,” the president said.

Trump followed up on Tuesday warning Americans to brace for a “hell of a bad two weeks” ahead, disclosing a best-case scenario of 100,000 to 240,000 deaths from the coronavirus pandemic.

The Washington Post reported that in addition to weighing the public health risks of lifting public gathering restrictions too soon, Trump has also been briefed by political advisers, who urged him to be patient in reopening the economy, “arguing that a spike in deaths could be even more politically damaging in November than the current economic downturn.”

But it’s not just Trump whose political fate could rest on how the federal government’s response to the coronavirus plays out. All states rely on federal assistance and possibly the whims of the president, and about a dozen of them will be holding gubernatorial elections. Eight incumbent governors are seeking another term and Bullock is challenging the Republican incumbent for a U.S. Senate seat in Montana.

And how these leaders work with the president to address this crisis in their states could be a factor in some voters’ decisions in November. In today’s highly polarized electorate, a Republican governor working closely with Trump and praising him won’t risk the political fallout that Democratic governors could if they are perceived as too chummy with the president.

Weingart recalled how former New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie welcomed President Barrack Obama to his state in the wake of Hurricane Sandy in 2012 and told residents they were “on the same team” confronting the devastation it left behind.

“When Christie ran for president three years later, there were a number of problems, but apparently in Republican caucuses and conversations that image stuck with many partisan Republicans as something that could not be forgiven,” Weingart said. “And that was when the country was less polarized.”