SALT LAKE CITY — The last few months at Three Rivers Hospital were quiet. Situated in the sparsely populated town of Brewster in Okanogan County, Washington, the rural hospital saw its number of patients plummet when Washington Gov. Jay Inslee temporarily banned elective surgeries in March.

But since the beginning of July, COVID-19 cases in Okanogan County, with a population around 42,000, have been increasing. Starting around July 9, Three Rivers went from an average of 4 or 5 patients coming into the emergency room to as many as 20 per day.

The northern area of Washington, which rests along the Canadian border, is largely agricultural. Essential farm workers have been contracting the virus and showing up at the Three Rivers’ emergency room, Scott Graham, the hospital’s chief executive officer, said. There have been five COVID-19 related deaths and a total of 550 cases in the county as of July 24.

As the coronavirus continues to spread across the country, hospitals serving rural communities are seeing surges in patients requiring critical care, according to The Associated Press.

Hospitals in Blaine, Idaho, Pendleton, Oregon, and Starr County Texas, have struggled to keep up with the sudden increase. Personal protective equipment has been harder to obtain, and emergency room staff have had to work longer hours with little relief.

On June 19, in Yakima, Washington, Virginia Mason Memorial, the hospital serving both the city and surrounding rural and agricultural community, announced it ran out of intensive care and non-intensive care beds. It had as many as 17 patients transferred out — some were sent to Seattle (about 145 miles away) while others had to wait for an opening.

“This is the day we have been fighting to avoid for months, when our hospitals can no longer provide their highest level of care because they are overwhelmed caring for patients with severe COVID-19 infection,” Dr. Teresa Everson, health officer for the Yakima Health District, said in a statement at the time.

The spike in cases was partially attributed to essential workers in the county, the Yakima Herald reported. About a third of workers in Yakima are employed in the agriculture industry.

The county had 24% of ventilated COVID-19 patients in the state, although it is only the eighth most populous county in Washington.

But before Virginia Mason Memorial ran out of beds, it started experienced staffing shortages. One ICU nurse at the Yakima hospital told a local outlet staff in her unit would go home at 7 p.m. and then return at 2 or 3 in the morning because “there’s no one else that can take care of them.”

Nursing shortages were a problem in rural areas before the pandemic, but surges in COVID-19 cases have made it even worse.

In a survey sent to hospitals with 25 beds or fewer, the Washington Health Workforce Sentinel Network found that not only were many nursing positions empty before the COVID-19 crisis, but that small hospitals also reported many nurses left to go help in other states facing “disaster situations.”

“You can physically create a bed, but if you don’t have enough people there to staff those beds safely you’re in trouble,” Joanne Spetz, director of the UCSF Health Workforce Research Center, said.

Staff shortages lead to less than optimal care, Spetz explained. “When the hospitals are overwhelmed, like what happened in New York and Italy, then the death rate shoots up. So it really is about saving lives and having enough beds is not sufficient.”

However, it is more difficult for rural hospitals to attract traveling or temporary nurses, especially when they are also competing with larger hospitals. “Rural hospitals don’t have pockets that are deep to pay that premium wage,” Spetz said. “They are competing against big urban players.”

Staffing isn’t the only thing smaller, rural hospitals have had to compete on.

“For items that are difficult to come by, they’re going to get served last,” Jacqueline Barton True, vice president of Rural Health Programs at the Washington State Hospital Association, said.

Barton True said getting personal protective equipment (PPE) and an adequate number of tests have been ongoing problems throughout the pandemic. “We’ve been able to import some PPE, but that shouldn’t really be the job of a hospital association. We’re doing it because it’s a need.”

In order to help rural hospitals facing both staffing and equipment shortages, Barton True said a big part of the solution is financial support. Many rural hospitals were already struggling before the pandemic hit — without income from elective surgeries, they are facing an even more precarious financial situation.

Three Rivers Hospital in Brewster requires a minimum of 20 elective surgeries a month to cover operating costs, Graham, the hospital’s chief executive officer, said. Since the governor lifted the ban, they’ve had about seven or eight. The hospital received funds through the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act and from the state, which is maintaining its payroll. But the money will run out by the end of the year if things don’t change.

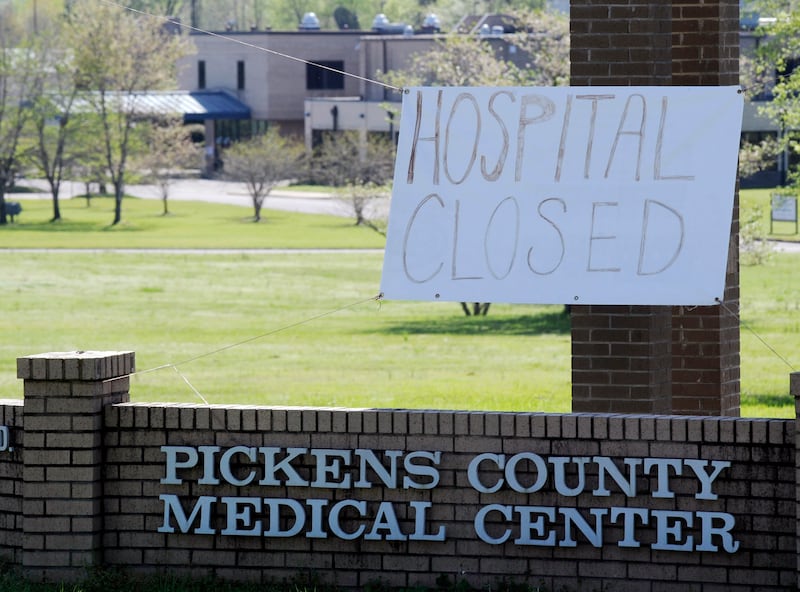

About 170 rural hospitals closed across the country in the last 15 years. “You can’t respond to an outbreak if you’re not there,” Barton True said. Twelve have already closed in 2020.

Rural hospitals like Three Rivers have found that while their emergency rooms are busier than ever, they are quickly heading towards insolvency. “We have kind of this split reality,” Graham said. “We’re having to make sure we expand funds on emergency services so that we can continue to help the community, but we don’t have the patient revenue to help us keep the doors open.”

Another important resource rural hospitals need is transportation, Barton True said. Many hospitals in Washington have agreements to transfer patients, and making sure patients can quickly and safely get care elsewhere is critical.

At Three Rivers, staff have been transferring patients that test positive for COVID-19 and are in need of care to Confluence Health in Wenatchee — about an hour’s drive away.

However, if Confluence Health is overwhelmed, Three Rivers may have to find a way to care for patients on its own.

“With a pandemic, one of the issues is that the other systems may be overtaxed as well. And so you may find yourself having to improvise, to make it work and we’re ready to do that too,” Graham, of Three Rivers, said.

However, the hospital doesn’t have an ICU unit and only has two ventilators.

“We’re not the best option for those types of patients and they really should go to an ICU. That’s our goal,” Graham said.

“Now, if the ICUs become full and there’s no place for them to go, then we’ll make do and do the best we can.”