SALT LAKE CITY — Americans don’t always agree on what businesses should be considered essential in a pandemic. But “circus” doesn’t make anyone’s list.

That’s why Julio Rosales, a circus juggler and father of two, has been out of full-time work since March and is currently making ends meet by selling cotton candy at a small fair in a shopping center in central Texas.

As such, Rosales and his family occupy one of the “pockets of serious trouble” that persist in the pandemic even as a majority of Americans say they are doing OK. According to new findings from the American Family Survey, about a quarter of Americans have suffered financially, and Hispanics are hurting the most.

More than half of Hispanics report some form of employment disruption in their family, whether it be the loss of a job or a reduction in hours or pay. And when compared to Black and white Americans, Hispanics are the least able to live off of their savings for 3 or 6 months.

The disproportionate effect of the pandemic on Hispanic families can partially be explained by their outsized participation in the service industry, analysts say. That segment of the workforce, which includes hospitality and restaurants, is among the hardest hit by lockdowns and other pandemic-related restrictions.

But there are other factors at play as well. And given the size of the Hispanic population in the U.S. — they are the largest minority, comprising 18.5% of the population in 2019 — analysts say their plight has an impact on the broader economy and society.

Larger households, less money

The financial stress comes as the size of many Hispanic households, already the largest in the U.S., grew even larger during the pandemic, according to the American Family Survey, a nationally representative poll conducted for the Deseret News and Brigham Young University’s Center for the Study of Elections and Democracy.

More than half of Hispanics said the number of people living in their home has increased since March, when the World Health Organization officially declared COVID-19 a pandemic. Among white respondents, a little over one-third said their household size had grown. (This could have been for any number of reasons, including the birth of a child or an adult child moving back home, the survey notes.)

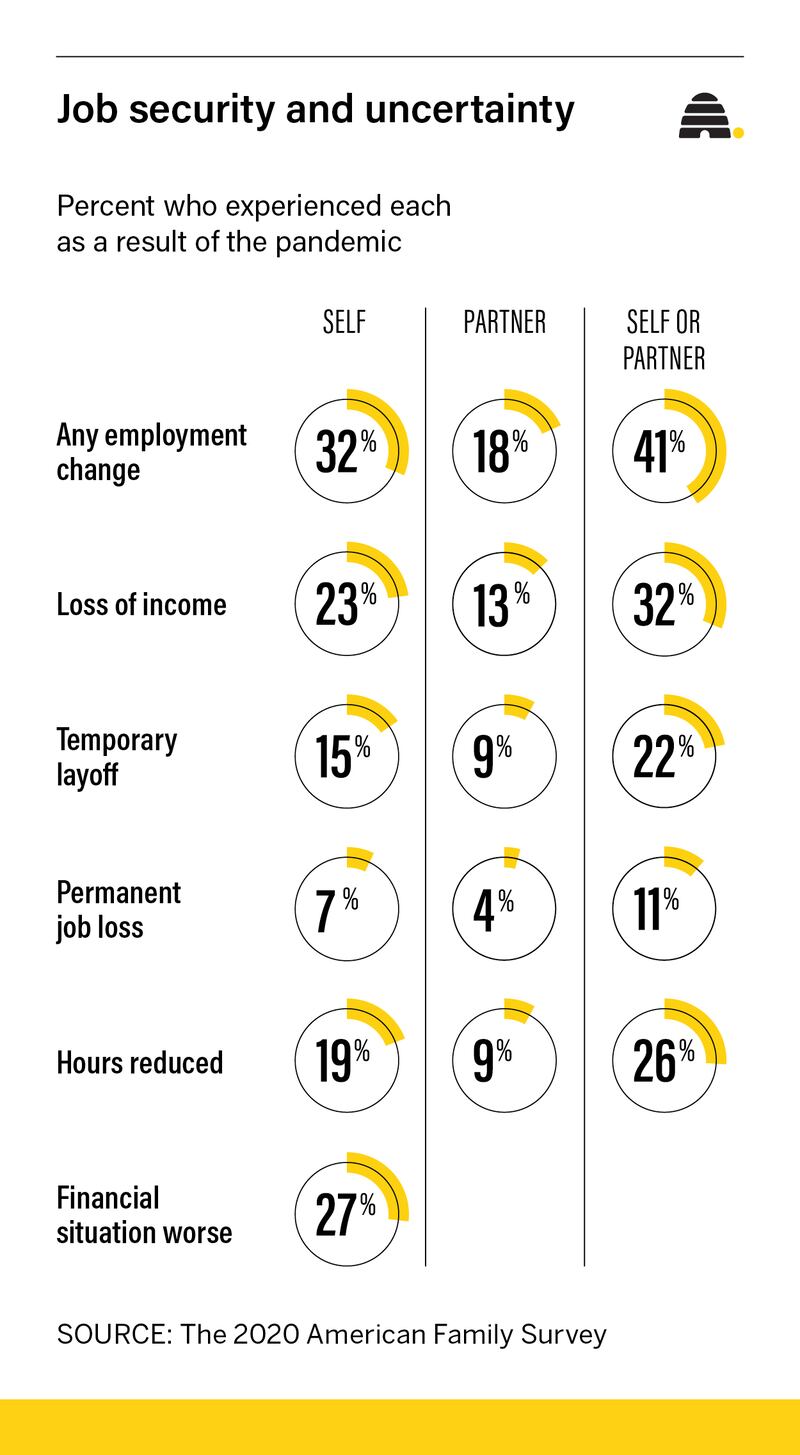

While both Blacks and Hispanics are disproportionately affected by the pandemic, in almost every measure of economic stress reported in the American Family Survey, Hispanics were suffering the most. These measures include:

— Employment disruption: 53% of Hispanics reported a change in employment for themselves or their partners, compared to 41% of Blacks and 38% of whites.

— Income reduction: 41% of Hispanic families reported less money coming into the house, compared to 34% of Blacks and 29% of whites.

— Overall finances: 35% of Hispanics said their financial situation was worse in July than when the pandemic began, compared to 28% of Blacks and 25% of whites.

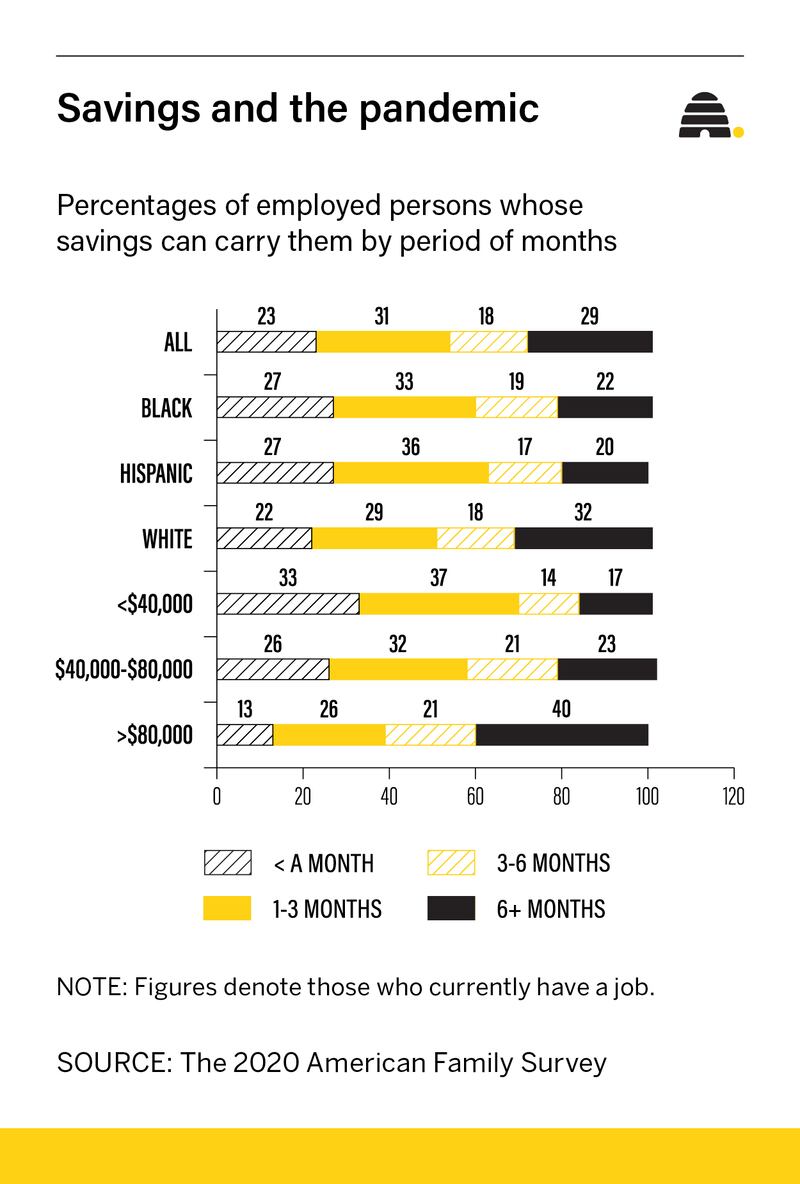

The survey, which represents the views of 3,000 people interviewed in July, with a margin of error of plus or minus 1.9%, did not measure the respondents’ overall wealth, but asked how long people could live on their savings: less than one month, 1-3 months, 3-6 months or 6 months or more.

Twenty percent of Hispanics said they could live for 6 months or more on savings, compared to 22% of Blacks and 32% of whites.

Rates of infection

Jeremy C. Pope, co-director of BYU’s Center for the Study of Elections and Democracy and a principal investigator of the report, said the survey did not delve into the reasons for the higher levels of employment disruption among respondents who identified as Hispanic. But he speculated that the findings could be at least partially explained by other research that shows higher rates of illness and positive COVID-19 tests among Hispanics.

“I have also wondered if their family networks make it easier to get the disease and cause more (employment) disruption, since most people pick it up through family or really close friends,” Pope said.

The American Family Survey reveals another disparity in the pandemic’s unequal effects: 36% of all Americans say they know someone who has contracted COVID-19, while 48% of Hispanics say they know someone who was infected.

Hispanic Americans account for more than 34% of COVID-19 cases although they comprise 18.5% of the population, said Lisa Cacari Stone, associate professor of health policy at the University of New Mexico. And Hispanics are hospitalized with COVID-19 at a rate of nearly 5 times the white population.

The hospitalization rate could be in part because one-quarter of Hispanics live in multigenerational households, compared to 15% of non-Hispanic whites, and older people are more likely to become seriously ill from the disease.

Other factors that predict infection are obesity, unemployment, limited English proficiency and being an immigrant, Stone said in a Sept. 23 seminar on COVID-19 and Latino health put on by The National Institute for Health Care Management Foundation.

“Disparate impacts of COVID-19 mirror and compound existing racial inequities in health and health care that are driven by broader underlying structural and systemic barriers including racism and discrimination,” she said.

But even when Hispanics aren’t infected with the coronavirus, they are suffering disproportionately high levels of economic pain because of the jobs they hold.

Federal data show that Hispanics are the least able to telework, according to Cheryl Abbot, an economist with the U.S. Department of Labor and Statistics. Only 19% of Hispanics could work from home during the pandemic, compared to 44% of Asians, 26% of whites and 23% of Blacks.

Hispanics were the group with the highest rate of unemployment nationwide in August: 10.5% compared to the national rate of 8.4%. This is in part because federal data show that 24% of Hispanics work in service occupations, compared to the national average of 17.1% in 2019.

A recent study in the journal Health Affairs found a correlation between the high rates of COVID-19 infection among Hispanics with household size and the percentage of workers in food service.

These factors combine to create a complex web of suffering in the families that the coronavirus has hit hard.

And they trickle down to every aspect of family life. Hispanics who were experiencing financial hardship because of the pandemic, for example, were also the most likely to report that they feel they are failing as parents, the American Family Survey found.

Their plight has the potential to ripple through society, as small businesses owned by HIspanics fail and families are unable to pay rent, according to a July report from the Brookings Institution.

According to the Abriendo Puertas/Latino Decisions National Parent Survey, conducted in June, nearly 4 in 10 respondents said someone in their household had lost health insurance during the pandemic, and about 1 in 4 of families who were struggling had turned to payday loans to get by. “This suggests a very rough road ahead for the economic trajectories of these families — particularly for the children in these families,” the authors wrote.

And they are the children that the United States will be relying on in large part to fill jobs left vacant as the baby boomers retire. Hispanics are expected to account for 1 out of every 2 new workers entering the workforce beginning in 2025, according to the Society for Human Resource Management.

Life in the pocket

Rosales, 51, has not seen his household size increase, which is a relief since he lives in a motorhome with his wife, who is 42, and their 20-year-old daughter and 10-year-old son. Nor has anyone in his immediate family contracted COVID-19, although he knows people who have. “We try to be careful, wearing a mask and washing our hands. But you’re at risk all the time when you’re working with people,” he said.

The financial toll of the pandemic, however, has been substantial since all three adults in the family worked for the Cirque Monte Carlo, which shut down in March. Rosales and his daughter are jugglers; his wife does a variety of things, including riding elephants. In a normal year, they would work for nine months, traveling to 15 states.

At one point, the circus reopened but it closed again after one week because of increased coronavirus infection rates.

For now, the family has evening work as food vendors at a small carnival in Stephenville, Texas, west of Fort Worth. He’s selling cotton candy and candy apples; she’s selling fried Oreos and elephant ears. Business is not good. “Yesterday we closed a little early, because there weren’t many people.”

Twenty-seven percent of Hispanics in the American Family Survey said they only have enough savings to live on for a month or less. Rosales said he’s already depleted his savings. The family has health insurance through the Affordable Care Act, and Rosales and his wife received a stimulus check, but they have not gotten unemployment benefits or food stamps although they applied online. “And the offices aren’t open so we can check and see what’s going on.”

“The stimulus check helped a lot. It was really, really good for us,” Rosales said, adding that he is hoping there is another, because he doesn’t know how long his current job will last.

“We’re working a little bit here, but I don’t know for how many weeks,” he said. He doesn’t know what the family will do next when the fair closes.