The patient is asleep, lying face down on an operating table in OR2 at the University of Utah’s Clinical Neurosciences Center, surrounded by a dozen people who do their jobs with swift efficiency, whether monitoring vital signs or guiding an implement to peel away scar tissue or regulating the cocktail of medication that keeps the patient under.

The overhead lights switch from white to green as the operation progresses, a single white light outlining only the area where the brain is exposed. Everything else by design fades into the green background.

For the next several hours, the neurosurgeon and his team focus solely on the patient’s well-being, removing a tumor that’s small but will grow dangerously if it’s left alone.

This is not the patient’s first brain surgery. They are removing a recurrent tumor.

But it’s not the neurosurgeon’s first brain surgery, either. Dr. Bob Carter estimates he’s done about 5,000 in his career. And he plans to do about 50 this year.

Carter is generous with his knowledge, a natural teacher. He mentions the book “Flow,” which describes the almost-magical feeling when everything clicks. The subtitle “Psychology of Optimal Experience” is what Carter finds as he operates: Neurosurgery has a rhythm and a very specific goal. That intense but comfortable focus will serve this patient well.

After the early morning surgery, when the patient is on the way to recovery and the family has received an update, Carter will remove the surgical mask and blue gloves and scrubs. He’ll probably replace them with dress pants and a nice shirt, though sometimes he wears a suit, depending on the day’s calendar.

Neurosurgeon is not his only job.

In late 2024, Carter was named executive vice president for health sciences for the University of Utah and CEO of the entire U Health system — all five hospitals and 12 community health centers and five medical education colleges. His purview extends to a $5 billion clinical enterprise with a $500 million research portfolio, a health sciences library, oversight of about 27,000 faculty and staff and the education of 6,400 students.

He’s going to have a long, very busy day.

The journey’s start

This month, Carter was inducted into the National Academy of Medicine. It’s an honor bestowed by election for outstanding professional achievement and commitment to service. For some, that’s a crowning achievement in a medical career, but Carter’s career has been anything but a straight trajectory, and he’s just months into a new adventure.

While he’s never worked in Utah before, the Beehive State is an important part of his history. He was born at Utah Valley Regional Medical Center in Provo in the early ‘60s into a family that would eventually grow to include eight younger siblings. When he was 4, the Carters moved to Ohio, and Utah was relegated to episodic memories of visits with relatives. His grandfather owned a dairy farm, now long gone, near Utah Lake. As a teen, he figured he might come back for college at Brigham Young University — and he did, courtesy of scholarships and working janitorial shifts.

Carter met his future bride, Jennifer Lewis, at Laval University in Quebec City, a pair of BYU students who’d never bumped into each other on the Provo campus, but instead found each other during a six-week French language program.

He completed college in three years, plowing through year-round to finish fast, but she got ahead of him when he left to serve a mission for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Paris. When he returned, she was starting a graduate school program. They wed in his senior year, and he finished his bachelor’s degree in chemistry in 1986.

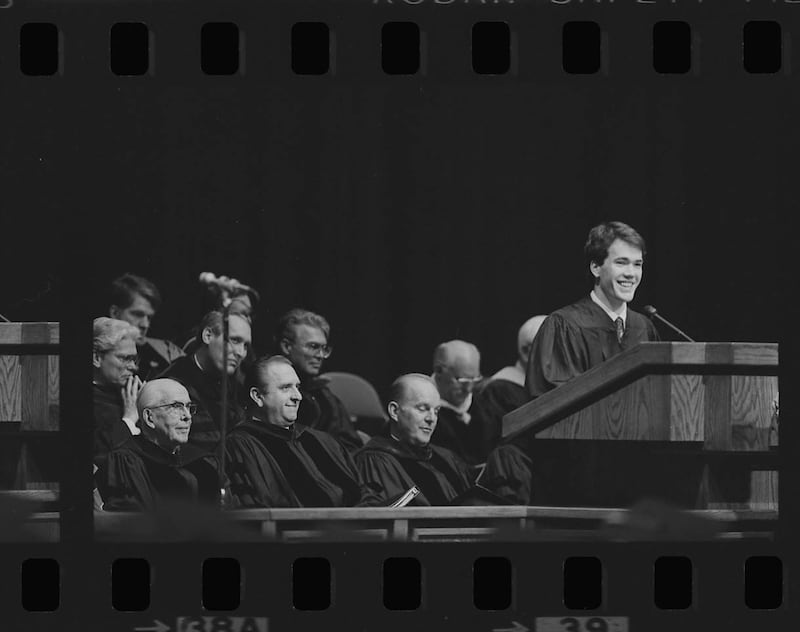

In a speech at the BYU graduation ceremony where he represented the class, Carter called learning a way to overcome life’s frustrations. “It offers new perspectives into difficult challenges and those perspectives allow us to pursue solutions to our problems along avenues we would have never guessed to explore.”

His career trajectory would later prove his point.

Medical school was his goal, and he was accepted to Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, so that summer, the couple packed up the little 1978 Toyota Corolla the previous owner had spray painted gray and they drove across the country, arriving at a hot, muggy city that was nothing like Utah or Ohio. “It was inner city and gritty and it had a flavor of vibrancy and energy, but also was just almost a shock of ‘Wow. This is a big city,’” he remembers.

The Carters loved it.

Jennifer Carter finished her coursework at Johns Hopkins to earn her BYU master’s degree, and her husband started both medical school and an epidemiology program, emerging with medical and doctorate degrees. He planned to be a urologist. During the medical program, which included both medical studies and lab work and took him six years to complete, Carter was part of a research team that first characterized a form of inherited prostate cancer. That turned out to be a very big deal. Friends said that even early on, he was clearly exceptional.

He was also being mentored by an incredibly well-respected urologist, Dr. Patrick Walsh, and his path forward seemed both set and exciting.

But Carter was open to emerging adventures. Pivoting in unexpected directions would prove to be a major part of his skill set.

Choosing a different road

Change started with a series of monthlong programs called externships at different hospitals during his final year of medical school. It was “incredibly late” in his medical education when he did one in neurosurgery, but that first day, his calling found him.

Carter was in the operating room to watch a neurosurgical team remove a benign tumor from the base of a patient’s skull, where it pressed on the brain stem. Unexpectedly, a resident who was going to assist was called away, and the surgeon invited Carter to join the inner circle at the operating table.

It was an unheard-of opportunity for a student and a life-changing moment. The surgeon noted he was good with his hands. Carter was hooked.

“It’s still so vivid in my mind, the beautiful anatomy, seeing the brain stem, the spinal fluid. There’s a little inside saying among neurosurgeons. We call spinal fluid the champagne of body fluids. It’s just really so beautiful, so clear,” he said.

Carter stayed an extra month, doing another externship before applying for a neurosurgery residency. He was eager to embark on the seven-year journey to become a neurosurgeon.

The juggling act

It’s possible that Bob and Jennifer Carter experienced the early days of parenthood a bit differently, though they both loved it. Carter, to this day, tells students not to hesitate to start a family while they’re training to be doctors. It’s too important and it’s not practical to put off life for “someday.”

“If you put off everything until you’re done and it’s all perfect, you might have regrets about not being invested in family along the way,” he’ll say.

Jennifer’s response is both wry and good-natured: “He had an awesome wife.”

During medical school, being a parent was more straightforward, she said. But Carter did his residency at Massachusetts General Hospital in an era when resident hours had not yet been limited and they were very, very long. Every third night, he was away, on call at the hospital. The two nights between, he often got home after 8 p.m.; the kids were already in bed. His morning shifts arrived before they’d begun to stir. There were stretches where he didn’t see the kids during residency.

His wife said she had a supportive network of friends and family that made it doable, if not always easy. Plus, in the middle of the neurosurgery residency in Boston, residents are allowed two research years, and those years were better for family time. He did his research at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, but had a more reasonable schedule to spend time with his family, which by then included four kids.

He was a natural as a dad, she said, while she had to learn to be a mom on the job. The oldest of nine, Carter grew up with younger kids and babies. She was the only girl in her family and one of the youngest. “I felt like from the start he was more comfortable with newborns and kids. He was often the one sleeping on the couch, holding the baby, getting up in the middle of the night to help out. When he was around, he was very hands on.”

Their children — Laura Tengelsen, Jessica Winfield, Alyson Bullock, Ethan Carter and David Carter — are now adults themselves, some with kids of their own, scattered across the country. They’re ages 22 to 36.

Those training days were a whirlwind of obligations, but Carter let nothing slide. Besides learning to be a surgeon, he served in his church’s bishopric in Baltimore and later did a five-year stint as bishop of a ward for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Belmont, Massachusetts.

Family time, while not very abundant, was always important. When they could, they camped and hiked in the early years when they didn’t have a lot of disposable income. As he earned more, they sometimes rented a house at the beach instead. Eventually, they were doing well enough for annual ski trips.

In the meantime, she’d worked as a linguist for the National Security Agency, but cut her hours as her family grew. Eventually, she opted to stay home with the kids.

While he was at MIT, Carter studied gene transfer and cell transfer therapy for brain cancer. He helped devise one of the first engineered T cells to create an immune response to brain tumors.

He calls that his “second medical first.” The first, of course, was the familial prostate cancer discovery.

So life was bouncing along, the family happy in Massachusetts. He was working long hours, but also prioritizing family and church and a growing group of close and loyal friends.

A ringing phone and another pivot

Medicine has two paths: academic or private practice, Jennifer Carter said. Private practice generates more money and that’s where most medical students go, but her husband chose academic medicine. She didn’t understand the choice at the time, “but it’s actually been amazing because you’re involved with the research, you’re always at institutions that are doing the most innovative work.“ He was teaching, researching and practicing in a career that would include Harvard University and Massachusetts General, among others.

The family was thriving.

Then the phone rang — another pattern as his reputation grew.

University of California San Diego was looking for a division chief. Would Carter consider applying?

Jennifer didn’t want to leave Massachusetts. She’d mostly lived on the eastern seaboard since age 12. They had family and friends there. It was comfortable. Their kids were doing well in school, had friends and were active in their Latter-day Saint ward.

But Carter was always up for a challenge and they decided to go for it. Later, she would be sad to leave San Diego. They stayed in California, a place he describes as “magical,” for seven years. Besides his gift for neurosurgery and managing a department, they had a shared gift for making friends, building community and finding meaning outside of work.

Carter said nothing short of being neurosurgery department chair at Mass General could lure him away. Then the phone rang again. That job had become available.

Carter had the day’s last interview, and as he headed for the airport, he figured it had gone pretty well. At the departure gate to head home, he learned just how well. The group making the selection had planned two or three rounds of interviews, winnowing choices, but an informal poll after the day’s interviews showed they all liked Carter. He was invited to “come back in a week or two to see if he could be the one.”

By then, Jennifer Carter had settled into the warm weather and delights of Southern California. “I have to give a huge shout out to my wife,” Carter said, noting she’d changed directions a lot for the sake of family. Over the years, she’s packed and unpacked and packed and unpacked, shifting kids and priorities as his career blossomed.

“A big part of my success was being able to have our family have stability,” Carter said. That stability’s name was Jennifer Carter.

Still, it was Massachusetts. They had friends there and it was quite the coup to be part of a neurosurgery program that was nearly 100 years old. “It was a place where a neurosurgeon could do so many exciting things,” Carter said.

The brain surgeons were changing lives in real time but also for the future of later patients and medicine itself. Back at Mass General, he was part of a team creating a cell therapy for Parkinson’s disease by taking a patient’s skin cell and growing it to become a stem cell. From there, they made it into a dopamine-producing neuron. Besides the incredible scientific discovery itself, they raised millions of dollars and came up with a way to produce the cells. In 2018, they did the first implant. Two years later they published what they’d learned from that patient, the first treated with their own autologous dopaminergic neurons.

“Incredibly exciting and the reason I was at a place like Mass General,” Carter said.

What they developed didn’t cure Parkinson’s, but the patient is alive and doing well and back to activities like swimming that had seemed lost forever.

His star was still rising in the field of neurosurgery. When Mass General and Brigham and Women’s Hospital combined, collapsing two of each department into one, Carter was named head of the combined neurosurgery department, possibly the largest anywhere, with close to 100 neurosurgeons doing a total of roughly 10,000 surgeries a year.

Embracing new challenges

But Carter was restless in a want-to-grow way, and had begun to wonder if he could make a different impact. He had worked with “tremendous medical center leaders” over the years, he said. He wondered if he’d like to be one.

Between San Diego and Boston, he has chaired a department for 15 years. “I could do it in my sleep. I want a new challenge,” he confided to his wife. “I’ve always wondered what it would be like to be CEO.” Jennifer said that while he craved personal and professional growth, she was wondering why they would leave friends, a home they loved and a job that’s possibly the most prestigious in the country for a neurosurgeon.

Even Carter thought it was an odd notion. He loved Mass General Brigham and they had a great life in Massachusetts. Plus, moves take a lot of work — and they get bigger the older you get, he later said.

But he couldn’t get the opportunity to lead health endeavors at the University of Utah out of his head — the chance to mentor and teach and help shape a health system’s entire course. He loved university President Taylor Randall’s vision for growth and wanted to see what the school could accomplish.

He also pondered something the dean in San Diego said back when he was being recruited years ago. The man said being in San Diego taught him a lot about waves and oceans and surfing. “The best time to catch a wave is well before it’s cresting,” he told Carter. “It’s just when you see it start to rise.”

Carter thought about that a lot over the years. Utah felt like a place “where we could catch a wave and do something special over the next many years.”

Going to the University of Utah would surprise a lot of friends, though. People joke that Carter was perhaps the truest of true blue, since he and his wife, as well as all five of their children and their spouses, went to BYU. He just smiles when asked what it’s like to switch colors and be at rival Utah. Ever the diplomat, he declined to say who he’d be cheering for whenever Utah and BYU meet on the football field.

But he points out that blood is blue when it enters the heart. When it leaves, it’s red. Both parts of the journey are essential.

He said Jennifer was a bit shocked when he applied, but Utah also had a few draws that amplified the appeal: They have a daughter and two granddaughters who live in Holladay. And their youngest son, David, is a pre-med student in his sophomore year at BYU.

Friends for life

Among Carter’s gifts are friendships, many of which stretch back decades. Dr. Mark Ott, the newly appointed inaugural dean of the BYU School of Medicine, was a resident at Johns Hopkins when Carter was a medical student. They had an incredible amount in common, including growing families with children of similar ages — eventually five children each — and a shared Latter-day Saint faith. Jennifer Carter and Emily Ott became dear friends. And as their careers sent them to different locations, the men stayed close, offering each other encouragement and serving as sounding boards.

At the time Carter matched in neurosurgery in Boston, Ott had taken his first real surgeon’s job there. The two families spent a lot of time together.

Eventually, Ott moved to Utah to be chief of surgery at LDS Hospital and later went to Intermountain Medical Center. Ott did surgical oncology and served in administrative and educational roles for Intermountain for more than 20 years. It was natural to ask his opinion as Carter contemplated a job in Utah.

While his new job added administrative roles, Carter has never given up surgery. Ott said his friend was “born to perform the extremely delicate and complicated neurovascular subspeciality of neurosurgery.”

He describes Carter as “brilliant, an incredible surgeon and a good person. He’s just very good through and through.”

Ott also admires his friend’s good humor, describing him as “very funny.” Adds Ott, “He would do anything for anybody that he could possibly help.”

And Jennifer Carter is just as accomplished, Ott said. “She made him even better than he could have been without her. She’s a humble, quiet person but gets a lot of credit for Bob’s success.”

Dr. Steven Kalkanis is now CEO of Henry Ford Hospital and Medical Group in Detroit. He’s another old friend. When he was training at Mass General back in the day, Carter was his chief resident, and their careers have been quite similar in the quarter-century they’ve been good friends.

Kalkanis said Carter is successful because his guiding focus has always been patient care. He credits Carter with teaching him to listen to the patient, No. 1, “despite what the radiographic films, the lab studies and the textbooks may tell you at the end of the day.“

He noted that “nothing takes the place of being able to walk into a waiting room at the end of a big surgery and look a family member in the eye and say, ‘We got it,’ or ‘We fixed it.’ That is Bob’s touchstone and that gives him enormous credibility with physicians, with colleagues, with nurses, with peers, with patients, with families.”

And, Kalkanis adds, “He’s the real deal.”

What he isn’t, several people asked about Carter volunteered without prompting, is arrogant. “Bob was always sort of surprising and delighting people with just how thoughtful, with just how collaborative and inclusive he is,” Kalkanis said.

In the field of neurosurgery, Kalkanis said, Carter has “always been ahead of the curve. And Bob is one of the few people in the universe I trust with the most important decisions I have to make personally, professionally.”

He also admires the Carters’ large and close-knit family and how they show up for each other. “I learned from him in that regard as well,” Kalkanis said.

A vision for U Health

Carter admits he didn’t realize in his younger years “what an incredible graduate medical center the U. has. It’s really an amazing place to get exposure to the health sciences.”

His role overseeing it all — including the schools of medicine, dentistry, nursing and pharmacy, as well as the College of Health — is quite unusual. Not to mention overseeing the hospital, the Huntsman Cancer Institute, the Nielsen Rehabilitation Hospital, Huntsman Mental Health Institute, University Hospital and all the rest of it, on campus and off.

When Randall and the search committee tapped Carter to replace Dr. Michael Good, Carter was an endowed professor of neuroscience at Harvard Medical Center and “Neurosurgeon in Chief” at Mass General Brigham. Besides “training carers and providing care,” he sees the health system he’s over as a place where people can learn and have professional and personal advancement, not to mention economic mobility — “so a real driver of positive change.” And he’s talking about all levels of staff.

Carter is also forming partnerships within departments, such as the neurosurgery collaboration with the engineering department and a tech company called Blackrock Neurotech. Engineers created the Utah Array, a set of electrodes that can be implanted on the surface of the brain. The invention was spun off into the tech company. The array underpins work with patients who are paralyzed or have a neurological condition like ALS.

Combining different specialties can give people disabled by disease “the chance to control their environment just by thinking: Turn off the light switch, turn up the music, write an email — life-enhancing activity that results from a collaboration between rehab specialists, neurosurgeons, engineers and others,” he said.

“This is an ecosystem where we can put these different parts together and create real value for new therapies and new ideas.”

In the few months since he arrived at Utah, Carter has done some reorganizing and created new leadership roles. “We’ve got a big vision, and it’s been fun and exciting to do every day, to get up and be energized. I look forward to coming to work.”

Jennifer Carter said her husband’s style is to let people do their jobs. He doesn’t micromanage. Carter’s wife and kids are all familiar with what he dubs the “E to P ratio.” It’s a lighthearted way for the family to remember to avoid an ego that’s more outsized than the actual performance merits.

Per Jennifer Carter, Carter’s own E to P ratio is healthy. He’s not overly impressed with himself and values that quality in others. “He’s down to earth, friendly, a genuinely nice, humble guy,” said his wife of 40 years.

Randall told the Deseret News the school was looking for a “visionary that knew the unique place of a health care system attached to a research one university and Carter’s background, his extraordinary excellence in both care of patients and his field and the research and education that he did at Harvard just really stood out to all of us.”

“The great thing about being in the job that I’m now in is that you see the whole scale of the medical enterprise and you can think about the strategic investments you want to make and how you can have impact at scale in a community like Utah or a nation,” Carter said.

The two men work very closely, and Randall describes Carter as collaborative and innovative by nature, “so if you’re trying to create something, he’s someone you always listen to. Too often our roles are problem-solving and what I find is he’s extraordinarily creative and always looking to grow the pie. I think the word these days is generative,” Randall said.

“He is one of the most interesting, inspirational individuals I’ve ever had the opportunity to work with,” Carter’s new boss said, “and I’m really excited to see how his leadership leads this university, our medical school and the University of Utah health care system in the future.”