The front page of the Daily Wildcat on May 1, 1995, covered the kinds of news stories you might find at any college newspaper. There on the University of Arizona campus, sophomores and seniors had recently protested over animal rights. The Student Union Building needed to be repaired. Alcohol abuse violations among students were up.

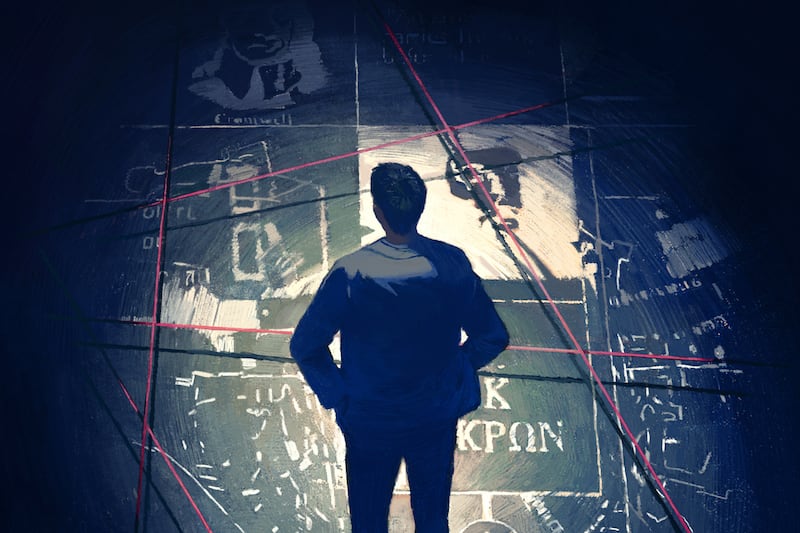

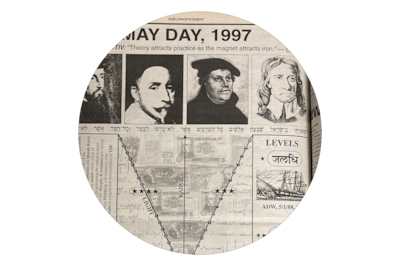

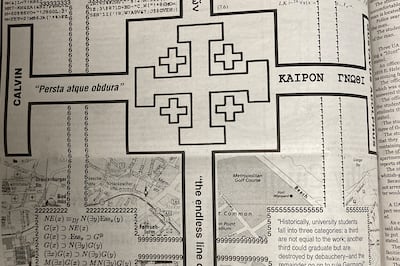

Bryan Hance, a freshman from a small suburb in central Ohio, scanned those stories and continued to thumb through the paper until he paused, finally, on page 16. He’d never seen anything quite like it. A full-page advertisement jumbled with maps, math, portraits, words and phrases he couldn’t make sense of. The ad referred to a group called “The Orphanage.” “MAY DAY” appeared in big bold letters at the top, and toward the bottom, a small illustration of a smirking man with two dots for eyes and ears drawn like potatoes. Hance was bewildered. Maybe this was the work of a fraternity? Or cobbled together during a fever dream?

A year later, again on May 1, he discovered a similar full-page ad. Among the maps and math equations was a quote from “Moby Dick,” in which Starbuck, first mate of the Pequod in the novel, says, “I will have no man in my boat who is not afraid of a whale.” The same crude drawing of a man smiled up at Hance as he scrutinized the page.

Yet another year passed and Hance was now a junior and had by then joined the Wildcat’s staff as one of the paper’s first webmasters. So when the ad showed up again, on May 1, 1997, he had the resources to start digging.

For two weeks, whenever he wasn’t in class, he was in the newsroom, lugging heavy bound volumes of old issues from the paper’s archives to pore over the newsprint in search of earlier May Day ads. He found one for 1994, the year he graduated high school, and 1981, when he was still in elementary. He did some quick math. For almost his whole life, it appeared that someone had paid thousands and thousands of dollars to place these ads in the Wildcat. But who? And why?

Those questions would consume Hance for years. And not just him. As the internet became more prominent, more joined in the search for answers. Today, in podcasts, YouTube videos and Reddit threads, Instagram, TikTok and Facebook posts, people around the world are trying to solve what’s become known as the “May Day Mystery.” Some sleuths have been at it for a quarter of a century. Many have become obsessed. One man was arrested.

In 2014, it appeared on a list of “conspiracy theories that need to be horror movies.” Later, Buzzfeed named it No. 1 among “11 super creepy modern conspiracies” sure to “make you believe.” Phoenix magazine once crowned the mystery “Arizona’s da Vinci code.”

Yet unlike popular enigmas that have emerged in recent years and morphed into harmful conspiracies — QAnon comes to mind — this one hails from a far simpler, analog time. What then, can it tell us about more pernicious cryptic phenomena in 2022? More importantly, as the May Day Mystery enters its second quarter century, will anyone ever solve it?

Kate Vesely grew up in Tucson, riding her bike along sun-bleached streets and learning not to touch the barbed spines of drooping cholla cacti. She stayed close to home for college, enrolling at the University of Arizona a few years after Hance. They never met, but they would have had something to talk about if they did cross paths. Like Hance, Vesely was a regular Daily Wildcat reader and she had noticed the ads that appeared in the paper every May Day. While her friends dismissed them as unhinged ravings, she was sure there was more there. “It was very clearly like a coded message,” she says.

She had always loved history, and she anxiously awaited the ads, wondering what past they might tread. After she graduated she’d always return to campus to pull the May 1 edition from a metal newspaper distribution box. She enrolled at the university again in 2002 to pursue a graduate degree, and she spent her spare time exploring a website she had learned of since college: maydaymystery.org.

Up popped a website that Hance had created. It included scans of every May Day Mystery ad — what Hance described as “The Texts” — since May 1, 1981, along with clues that the mystery had roots reaching back even further.

Vesely spent hours on the site, scrolling through the ads and seeing the similarities over the years, the same imagery and repeated words and, more often than not, that drawing of a smiling man, sometimes with four stick-straight lines for hair, sometimes five. When she wasn’t working on grad school assignments, she was studying the texts, searching the internet for leads or slouched in front of a microfiche machine at the library.

In 2009, nearly 15 years after Hance saw his first May Day ad in the Wildcat, Vesely emailed him to see what he thought about starting a Facebook group. There, she figured, people could puzzle over the clues together. With Hance’s blessing, she created Mayday Mystery Fans and started sharing theories and asking questions to a growing community of people just as gripped by the ads as she was. Several years later, she began visiting Reddit, where there are ongoing conversations about unsolved mysteries. She hoped to draw on fresh perspectives. But while she gained new insights into different elements of the ads, she felt no closer to solving what she’d now spent more than a decade thinking about.

Still, over the years she had started to develop a hypothesis. In the 1970s, she thinks, a “collective of brilliant geniuses” attending the University of Arizona formed some sort of intellectual fraternity, using the newspaper to communicate with each other about subjects that were important to them. The ads maybe started as a game and turned into a tradition.

She could imagine young, cerebral students hungry to explore and exchange ideas about science, math and philosophy. But who were these bright shiny minds she pictured meeting at Cochise dorm, a residence hall with impressive Roman columns that once only housed men? Maybe they gathered around the big stone fireplace that anchors the building’s lobby, or whispered furtively in the shared bathrooms on the third floor. This origin story is purely speculative, Vesely knows, but not far-fetched. Because she knew of one person who fit into her hypothesis almost perfectly.

He had been a University of Arizona student in the late 1960s, studying philosophy, and later earned his law degree there. The ads have contained more than a dozen different languages; he reportedly spoke eight, including Latin, Hebrew, Russian and Greek.

Vesely had discovered that this man, Robert Hungerford, by then well into his 60s, kept an office in downtown Tucson, not far from where Vesely worked for the Pima County criminal justice system. One hot, summer day in 2013, she summoned the courage to drive there before a meeting. She found his office address online, parked out front, and nervously walked down the stairs to the building’s basement where she found Suite 16 and a business card on the door that indicated he was retired. When she knocked, no one answered. Before retreating back outside, she left a note.

“I’m a longtime follower of MDM,” she wrote, referring to the May Day Mystery. “I was in the neighborhood and wanted to say hello. If you ever keep office hours and wouldn’t mind a visit, please let me know.” She included her email and left. The next day, a message was waiting in her inbox.

Back during his senior year, Bryan Hance, frustrated by his lack of progress in unlocking the puzzle, appealed to the relatively new internet. “I have unraveled the Mayday pages as far as I can, and I am far from my goal,” he posted on the site he’d built. “I need your help.” It was an online message in a bottle, but it landed on an unexpected shore.

That May, after Hance hurried to campus to get a copy of the Wildcat to see that year’s ad, he opened his email and found a message signed, “The Orphanage,” the same name that had appeared in the ad that caught his attention as a freshman.

“The day you can see the door,” the email said, “you will be welcomed inside.”

The laconic missive only served to pull Hance further in. He didn’t leave Tucson after graduating. Instead he worked for the university and started a side business, writing software products. He kept researching the clues in the ads when they were published each May and posting them on his website, along with correspondence he received from “The Orphanage,” rare coins and news clippings, postcards and letters with stamps from Nairobi, Las Vegas and beyond.

Today, in podcasts, YouTube Videos and Reddit threads, Instagram, TikTok and Facebook posts, people around the world are trying to solve the May Day Mystery. Some sleuths have been at it for about a quarter of a century.

Sometimes Hance would get phone calls from people who were apparently from “The Orphanage” advising him of a forthcoming ad. Other times, he heard from people like himself who were trying to solve the mystery. In the early 2000s he had been emailing with someone who insisted on meeting in person so that she could show him her research. Hance biked to one of his favorite cafes in downtown Tucson to hear what the woman had to say.

He was reading at one of the restaurant’s tables when she walked in. Only it wasn’t a woman — it was a girl young enough to be accompanied by her father, who had driven his daughter nearly two hours from Phoenix to present her findings. As her dad sat to the side like a chaperone at a school dance, the girl pulled out a thick blue three-ring binder.

Hance listened as the girl, whose name he can no longer remember, made her case: the person behind the May Day Mystery was the Zodiac Killer, the pseudonym of a serial murderer who terrorized Northern California in the late 1960s.

One page of her research, titled “Stamp Fixation,” compared images of envelopes the Zodiac Killer sent to newspaper editors to the envelopes Hance had received from, apparently, “The Orphanage.” Hance saw the killer’s infamous ciphers next to some of the characters that had appeared in the May 1 ads.

“Look,” Hance said. “I’m going to be absolutely honest with you. I don’t think this is it.”

“Well,” she said, before leaving. “I just want to let you know I’ve sent all this to the FBI.”

In April 2022, I traveled from my home in Austin to Tucson, where one Sunday afternoon in April, I met Kate Vesely at El Charro Cafe, the oldest Mexican restaurant in Tucson. I plied Vesely for her thoughts about the ads and the mysterious Robert Hungerford, the attorney she left a note for back in 2013.

Hungerford had long been rumored to be the go-between who, every year, for decades, phoned the Daily Wildcat to place an ad in the May 1 edition. He has hinted as much — all while maintaining that he himself is not “The Orphanage,” just the lawyer hired to facilitate his secretive clients’ ad purchases.

I was hoping Vesely might help me meet Hungerford. They had started up a correspondence in 2013 and continue to message each other occasionally, but she’s never seen him in person. So after lunch, Vesely and I drove past the county courthouse where she works and parked outside of Hungerford’s office like she did nearly 10 years earlier.

Now the front door that she opened back in ’13 was locked, but peering through the glass, she pointed out the stairs that she had descended with trepidation, hoping to find the lawyer and maybe some answers to the mystery.

Walking around the side of the building, I tugged on another door and was surprised when it opened. We ducked into the dimly lit hallway with exposed concrete floors and garbage bins at one end, looking for a way to the offices. But it was another dead end.

Hungerford’s identity as “The Orphanage’s” occasional lawyer and errand-runner is not a secret. Brett Fera worked at the Wildcat as a student and later became director of Arizona Student Media at the university and he recalls talking to the courteous, professional man who called each year to inquire about advertising in the May 1 issue. He seemed to use no more words than were necessary, but wasn’t impolite — maybe just from a different era.

Hance was on staff at the Wildcat when he learned who Hungerford was. And for a while, he says, he was determined to know more. He started to try to dig into his past. He even met him in person when, he says, Hungerford hired Hance to fix his computer. Hance would try to get Hungerford to talk about the mystery but he didn’t reveal much, Hance says. As he was with Fera, Hungerford was crisp and businesslike, and not about to talk to Hance about the May Day Mystery in any substantive way.

Online, however, Hungerford is playful — in his correspondence with Vesely since that first email, and in the Facebook group, where his avatar, the default white silhouette of a man, encourages the mystery’s fans without ever really showing his hand. When I sent him a message in February seeking an interview, he declined, saying everything I needed to know was already on Hance’s website.

“I am of no interest to anyone, including myself,” he quipped.

The faintest sketch of Hungerford’s formative years can be found in old yearbooks and newspaper clippings. Before enrolling at the University of Arizona, he was a student at Phoenix College, where he belonged to the “13” Club, described as “an honorary men’s organization composed of 13 of the most outstanding men on campus.” In his senior yearbook photo from the U. of A., dressed neatly in a jacket and tie, he doesn’t look unlike the drawing of the smiling man in the May 1 ads, with hair shorn close to his scalp, brows near horizontal across his eyes, and a sly smile.

He’s given a few interviews, though they’re not exactly illuminating. But after another volley of messages with me, he relented, somewhat, and said I could ask two questions about the mystery that his clients had authorized him to answer. I asked what the motivation was for the people behind the May Day Mystery to start it and keep it going, and what will happen if and when someone solves the mystery.

The motivation, Hungerford said in a Facebook message, is “total social/theological transformation, incipit: 8/30/69.” As for what will happen: “a dramatic transformation, beyond any sea change.” Hungerford said I “would need to experience it (myself) in order to report the Gestalt.” I looked up the last word. Gestalt, according to the dictionary, “is something that is made of many parts and yet is somehow more than or different from the combination of its parts.”

On April 29 of this year, Hance, who’s now 46 and lives in Portland, Oregon, woke up to feed his three cats, brewed a pot of coffee and descended to the basement office he calls his “nerd station.” He moused through the three computer monitors on his desk for the next 30 minutes, checking his work email — he’s employed by a yacht company — and then turned his attention to his personal email. There it was, another spring, another familiar subject line: “May 1, 2022.”

Since the Wildcat stopped printing regularly in recent years, Hance had been receiving the May Day announcements directly. A PDF was attached but he didn’t have time to open it yet. It wasn’t until the afternoon that he posted on his website and shared a link in the Facebook group.

“May Day 2022,” he said. “It’s a big one.”

There were familiar symbols and characters. Images of stamps featuring Martin Luther. The pyramid on the dollar bill and the date 5/1/72. Different drawings of the smiling man. The guitar tabs for “Hotel California,” by The Eagles, and an approximate passage from Shakespeare’s “Macbeth.” Within two weeks, nearly 200 comments had been left on the post hypothesizing what it might all mean.

Hance has now spent the majority of his life with the May Day Mystery. “It’s the longest thing I’ve done,” he says. When we first spoke, I wondered how this cryptic phenomenon is different than newer, more pernicious conspiratorial strains like QAnon? Unlike disinformation that misleads and manipulates its audience to believe something false, Hance told me, the May Day Mystery is more like a mirror: When people look at the ads, they see what they want to — whether it’s the history of Protestantism via images of Martin Luther, or mathematics via all those tantalizing equations that appealed to a young computer science major.

And so over the years he’s moved boxes of old, yellowed Wildcats and other documents — like the binder of evidence to support the Zodiac Killer theory — from home to home. When he looks back at the old issues he recognizes the bylines on the sports articles; he remembers the late nights in the newsroom. They smell like the past.

The day after meeting with Kate Vesely, I visited the Daily Wildcat newsroom. This isn’t the same dingy spot where Hance worked as the paper’s webmaster. That building has since been renovated and the Wildcat, and its archives, have moved up the street. I pulled heavy collections of old issues off a shelf to see the May Day ads for myself.

After looking at the ones I already knew existed, I messaged Hungerford on Facebook to ask if there were any predating 1981. The mystery originated in 1969, when he was a college senior at the University of Arizona.

“Very definitely,” he said. Encouraged by his quick and succinct response, I wrote again to see if they were always on May 1.

“Some were, many were not,” he replied. When I told him I was looking through old issues, he said he wanted to save me from “hours and hours of fruitless digging in old dusty papers.”

“The initial announcements, due to the tumultuous times, were not nearly as evident as 1981 forward,” he said. “In short, you would have to be INSIDE to recognize them. There is plenty from 1981 forward and much more forthcoming.”

In 1998, Hance appealed to the relatively new internet. “I have unraveled the May Day pages as far as I can... I need your help” It was an online message in a bottle, but it landed on an unexpected shore.

He encouraged me to “remember what was happening in the mid to late ’60s, especially in 1969.”

When I had asked Vesely why she thought there was such apparent radio silence between that year and 1981, she speculated that the men involved got married and had children. They were busy raising babies and taking care of their families. Hungerford suggests the reason was much less mundane: the ads couldn’t be more explicit because members of “The Orphanage” would have risked arrest. This dovetails with some theories that the ads are political and linked to unrest from that era. One TikTok user popular among May Day fans has posited that “The Orphanage” is so named because it’s made up of ex-members of activist groups such as the Weathermen, which formed in 1969 in opposition to the Vietnam War.

I didn’t think I could solve the mystery, but I thought I might have a shot at finding an announcement from the 1970s. I ignored Hungerford and started to slowly page through May 1 editions from that decade. By the time I started to wonder if there was a hidden meaning behind a record store’s “May Day Sale” ad, I put the archived issues back on the shelf.

Federal agents never contacted Hance about the young girl’s theory that the Zodiac Killer was behind the May Day Mystery, but for years he has considered calls and emails from people who believed they had solved the clues, or at least had a theory about them. It’s performance art. It’s an alternate reality game. Robert Hungerford is “The Orphanage,” and has been placing these ads in the newspaper alone. Hungerford is acting on behalf of a group of people, as he claims. This is the work of a secret society, or someone with mental illness. Sometimes, Hance is the one being incriminated. He wasn’t just a college student who stumbled upon a decadeslong puzzle — he’s complicit in the mystery, and playing dumb.

Another theory claims that Hance was connected to Hungerford by way of a company Hance formed to sell a software product he had created. Hance vigorously denies this. Others see Hance’s perceived indifference to pursuing Hungerford’s real role in all of this as a clue. It’s true that Hance is far from the most rabid May Day Mystery obsessive; one was once arrested for rummaging through Hungerford’s garbage. But Hance says he’s never wanted to solve the mystery by pulling back the curtain to see who was behind it. That felt like cheating. He wanted to figure it all out on his own.

Now, though, he doesn’t think he’ll ever solve it. Neither does Vesely. But she’s comfortable never knowing what, really, the May 1 announcements are all about. She’s just happy knowing the enigma exists.

“There’s this gigantic universe full of mysteries of things that we’ll probably never know, in my lifetime,” she said. “But I have my own little mystery right here at home.”

This story appears in the November issue of Deseret Magazine. Learn more about how to subscribe.