As an only child whose friends lived far away, I spent many afternoons in the backyard playing catch alone. I’d throw a tennis ball, a racquetball or one of those dense rubber balls from the grocery store against the cinder block wall of our home — away from the windows — and imagine entire baseball games or specific scenarios. The ball always found a home in my trusty mitt: a brown Wilson with a basket pocket, black trim, a finger hole and a velcro wrist strap. I loved those games, almost as much as the real thing.

My first baseball team was the Astros, in a local rec league. Later I played for the Giants, then the Cardinals. That brown Wilson stayed with me, often fielding tosses from my friend Henrique. We met in third grade and he became my “cousin” on the paperwork so we could always be teammates. We had a similar skill level — which was, sadly, not very high. By eighth grade, neither of us was talented enough to keep playing. Around that time, the strands holding my glove’s fingers together snapped. The dream was over.

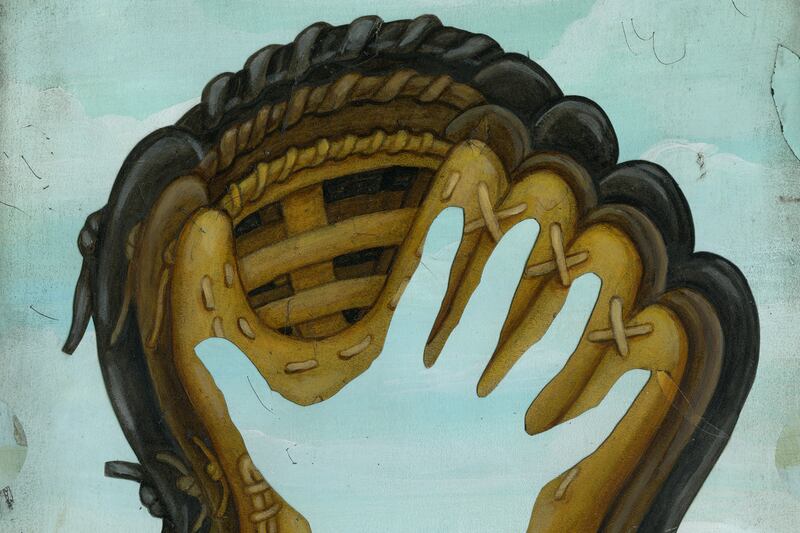

My parents found it strange when I insisted on a new glove, but insist I did. A baseball glove belongs to you not because you own it, but because you make it your own. With each grab, each drop of sweat, the leather molds to your hand until it fits you — and you alone. They bought me a maroon Rawlings with a “trapeze” weave-patterned pocket, a finger rest and tan trim. I used it to play catch with Henrique and field balls off the wall in my parents’ backyard. Later, I wore it through three seasons of college intramurals, where our team went from winless to the championship game.

A few years ago, my dog tore it to bits. I was heartbroken, but my wife knows me. For my next birthday, she gifted me a cream-colored Marucci infielder mitt with an I-patterned pocket and a padded wrist. She’s a former softball player herself, so we spent many afternoons tossing a ball around Memorial Park in Provo, Utah, even after our son was born. It wasn’t competitive play, but I considered that glove well broken in.

Then my car was burglarized. It made me think of the 74-year-old Texas man whose wife posted on social media looking for someone to play catch with him a few years back. A dozen strangers showed up, from high school players to fellow retirees. He said baseball was a work of art. That’s how my Marucci looked to me, laying among the other left-behinds on the back seat of my car. The thief even took my son’s diaper bag, but left my glove behind. Maybe a mitt just wasn’t worth anything to him. Or maybe he knew that a baseball glove isn’t a commodity you can trade. It’s a project you do for the love of the art, and it can never belong to anyone but you.

This story appears in the May 2025 issue of Deseret Magazine. Learn more about how to subscribe.