Fern Baird left Ketchum, Idaho, past noon on October 19, 2020. She pointed her black Subaru north, up state Highway 75, the two-lane artery that follows the Big Wood River through the flat, fault-bound basin that splits the Boulder and Smoky mountains. Twenty-odd minutes later, she turned left onto the fine gravel road that leads to the Prairie Creek trailhead. At 1:17 p.m., Baird, who was 62, clicked open a brown box at the end of the parking lot and signed the registry inside. She was headed “to the lake and back.” Then, Baird stepped up the trail, into the mountains, and disappeared.

Last August, nearly four years later, 22 volunteers with the Fowler-O’Sullivan Foundation took the same drive north from town. They parked at the same trailhead and signed the same log. They trod, as best they could reason, the same paths Baird took that October afternoon. At the most basic level, they were looking for clues — pieces of gear, scraps of clothes, anything that might lead to Baird’s bones. But beyond that, for Baird’s friends and her family, they were looking for answers.

Named in honor of Kris Fowler and David O’Sullivan, a pair of hikers who went missing on the Pacific Crest Trail, the Fowler-O’Sullivan Foundation steps in when search and rescue gives way to search and recover — a space that Executive Director Cathy Tarr found scattershot and ineffective when she first ventured to help find Fowler in 2017. Nearly eight years after its namesakes vanished from the trail, the organization continues to search for the remains of lost hikers once authorities stop. Their record — five bodies found, seven cases open — makes them one of the most active and, so far, successful groups working in that arena across the American West.

Under Tarr, Fowler-O’Sullivan united a growing company of volunteers to scour wilderness, both on foot and online, with obsessive dedication. Its methods mix brute force and shoe-leather detective work with a drone-driven digital approach. The common thread: thousands of hours seeking, and thinking about, missing people volunteers have never known. From that has grown something like the foundation’s emotional mission, supporting those who loved the lost and assuaging the stymied grief of those grappling with the unknown and the unknowable, a state psychologists call “ambiguous loss.”

No one gets paid, but Tarr is full time. She’s involved in every aspect. When snow shrouds high alpine clues, Tarr migrates south to the deserts of Southern California and Arizona. When the desert gets too hot, she heads north with the thaw to the Cascades.

Search and rescue is a growth industry. In Utah, for example, reported missions for missing hikers alone increased significantly in the 20-year span from 2001 to 2021, the most recent full year logged by the state. Grand County, which encompasses Moab and its surrounding recreation hotspots, plans to spend $554,992 on SAR operations this fiscal year; in 2020, it spent $178,074. But search and recovery — Fowler-O’Sullivan’s purview — remains an afterthought. If it had the means, the foundation could be working on 10 times as many cases as it is at any point, according to Tarr.

“There are always missing hikers,” she said. “There are missing hikers we don’t even know about. I can’t think of a time when we won’t be working on a case.”

As the group’s profile grows, so does the work. In 2023, Fowler-O’Sullivan search volunteer and former Forest Service ranger Andrea Lankford’s “Trail of the Lost: The Relentless Search to Bring Home the Missing Hikers of the Pacific Crest Trail,” a narrative chronicling the search for Fowler and two other missing PCT hikers, became a New York Times bestseller. Since then, Tarr has gotten more calls from wider areas — missing people, desperate families, more sojourns to the sadder side of life.

“Cathy is seven days a week,” Sally Fowler, Kris’ stepmother, told me last fall. The women met not long after Kris Fowler went missing; by now, they’ve known each other almost a decade. “I reminded her the other day, ‘Cathy, every time I talk to you, you’re either about to go look for the remains of a human being, or you just got back from looking for the remains of a human being.’ I try to talk her into taking a few deep breaths in between things. It’s a lot — it’s like a hospice worker.

“To me, that total strangers go out there and search for someone they didn’t know — just because it’s the right thing to do — it’s amazing.”

Kris Fowler started the PCT on Mother’s Day. He came to the trail between chapters in his life. At 34, his seven-year marriage had ended — painfully, but, by his family’s account, amicably — a year prior. He left his job at a Florida logistics firm and returned home to Beavercreek, Ohio, where he regained his footing. The next step was toward Wyoming for a seasonal construction gig and a chance to see a new part of the country. When summer ended, he had enough money and time to commit to a long-standing dream. Fowler got a permit for the PCT and started preparing in Colorado with a hiking buddy. They reported to Campo, California, an unincorporated town sidling the Mexican border, and Kris agreed to check in with his parents every two weeks for however long it took, starting with his first day: May 8, 2016. That morning, Sally Fowler’s phone pinged two time zones away and a picture came through of Kris heading north on the trail. “Happy Mother’s Day from the PCT,” the message to his stepmother read. “I love you.”

The son of a Navy sailor, Fowler was a natural athlete. When he put his head down, he could cover 25 miles a day. But he had a wanderer’s temperament, his stepmother said; he cared more about “smelling the roses” than making good time and preferred to hike in sandals to feel the trail beneath his feet. Fowler liked to take photos, too, and soon after setting off, his partner outpaced him. They decided to split up — nothing unusual on long hauls — and to keep in touch throughout the trip. Every two weeks, as promised, Fowler called home.

In October, Kris reached Washington and the calls stopped. Sally Fowler messaged a hiker Kris had befriended on the trail. Kris had texted her on October 12, the hiker said. He was having phone trouble and was looking for a new charger. Sally Fowler let it slide.

Another week passed without word. By October 23, she was convinced her son was missing. The last person to see Kris Fowler dropped him near a trailhead at White Pass on October 12 — mile marker 2,294, 356 miles from trail’s end. It took more than a week of negotiations for Sally Fowler to convince authorities, she says, but on October 31, the Yakima County Sheriff’s Office agreed: Kris Fowler had disappeared on the PCT.

The two-week search spanned five counties. Sally Fowler flew out to join. She supported her son’s outdoorsman streak but isn’t a hiker herself. She stayed as long as she could. The people she met were gracious. Washington Search and Rescue workers ran one of the largest, longest searches the area had ever seen, Fowler said. And the place was beautiful: high, hanging meadows and emerald groves, every inch alive. It was the sort of landscape Kris had set out to see.

Soon, though, she had to return home. From the plane she looked out at the forests that fringe Mount Rainier and cried. She knew in her mind that down there, obscured by autumn snow and trees, was her son. But until he’s found, part of her will never be convinced.

“I say that my head knows he’s gone,” she says. “My heart hopes he’s braiding hair in a commune somewhere, but my head knows he’s on that mountain.”

“There are always missing hikers,” she said. “There are missing hikers we don’t even know about.”

The weeks and months following Kris’ disappearance hollowed her out. She was exhausted and emotional, working full days from her home in Ohio and spending nights online, running down any lead that might track down Kris in the mountains of western Washington. She didn’t know what else to do.

“They’re wonderful, amazing human beings,” she said of the crews and volunteers that ran the operation, “but at some point reality says it’s time to call off the search. Some people give up once it goes from rescue to recovery, but (others will) go back out to chase down a clue. In the meantime, you’re left on your own to start digging and looking for the breadcrumbs.”

Fowler started getting calls from people with half-trained dogs or strong hunches. Psychics came out of the woodwork with ideas of their own; a check would pull things into focus. Fowler is high-energy and no-nonsense, but she was running out of ideas. Low on strength, she was beginning to listen.

“If Elvis rode in on a unicorn and found my son, I’d be OK with that,” she said.

Fowler was surprised and disappointed there was no structure in place to help. She encountered practical problems, too: Without a body, she couldn’t get a death certificate. Without a death certificate, she couldn’t forward his mail or cancel his cellphone plan. Kris had a car — she couldn’t sell it. The tags expired, and she couldn’t register it. It sat in his dad’s driveway, illegal to drive, a reminder of a missing son.

“Your loved one is missing, and especially in the first year you haven’t wrapped your mind around the fact that it’s probably not going to be a good outcome,” she said. “You still have hope. And you can’t imagine your loved one being left out there, with no one who cares enough to find them. Until you deal with this, you just think it’s like TV, with hundreds of people linking arms and walking side-by-side through a field until they find them. And that is not what happens. It’s not even close to the truth. That’s a snapshot — one moment of one day.”

Her life went on anyway. Eight months after Kris disappeared, his father — Sally’s ex-husband — died of cancer. Mike Fowler’s obituary stated that he was survived by a son. Sally Fowler went to Mike’s funeral, but never had a memorial for Kris. She doesn’t plan to.

At night, Sally leaned on social media for tips.

In 2017, she got home from work and opened Facebook. Her group, “Bring Kris Fowler/Sherpa Home,” approached 10,000 members. Fowler sorted through her messages and connected with a woman who said she wanted to help. Her name was Cathy Tarr.

Cathy Tarr doesn’t fit most archetypes of serious hikers. With her shoulder-length, red-brown bob and trained, managerial cadence, Tarr comes off like an aunt who found the right rungs on the corporate ladder and climbed, comfortably, toward retirement age. Yet she’s spent nearly every day of the last seven years unpaid, searching for people she’s never met.

People who fixate on these sorts of cases are often touched by loss one way or another. Some are battered by it, warped into thwarted grief. Others are just brushed. Tarr’s scrape was with Kris Fowler, missing somewhere near Mount Rainier in the fall of 2017.

As a new empty-nester, hiking was meant to be Tarr’s next act. A pharmacy technician by training, she left Walgreens after overseeing six stores in northern Virginia. Tarr soon fell in love with New Hampshire’s White Mountains, and among them wandered into the domain of long-distance hikers. For those on the last northern stretches of the Appalachian Trail, she was a regular “trail angel” — an endearing term for a volunteer who offers a bit of accommodation (or civilization) to those long in the woods. She traded her kindness for their inspiration. Tarr herself began hiking farther and farther distances. Exploration turned to training, and she fixed her sights on hiking one of the American through-hiker’s “Triple Crown”: the Appalachian Trail, the Continental Divide Trail or the Pacific Crest Trail. Two years after starting to hike seriously, her permit came through. In April 2017, she’d report to Campo and head north on the PCT. The trip would span 2,650 miles and take around six months.

She went back to New England that winter to practice on ice, using crampons and microspikes — skills she’d need through the suspended winter of June in the Sierras, and again, months later, in the erratic fall of the Cascades. She was riding with a friend through Maine when another driver pulled out in front of them. The collision ignited Tarr’s airbag, which blew into her chest with a crack. The driver was OK, but Tarr couldn’t breathe. The impact fractured her sternum. She wouldn’t be hiking the trail that spring.

Tarr wandered west anyway. In Arizona, she started seeing fliers with pictures of a tall young man in sandals. He had long, wiry limbs and smiling eyes set between a bandana and a beard like straw thatch. His trail name was “Sherpa.”

Kris Fowler

(Sherpa)

Last seen October 12, 2016 near

Packwood, Washington.

Tarr set out to join the search. She started looking and stayed along the PCT until the snow blanketed northern Washington. Clues concealed, she went south. After the first set of fliers came a second: David O’Sullivan, a young Irishman assigned a start date so close to Tarr’s that, had her plans gone as scripted, they might have passed each other on the trail.

“When you’re on one of these trails, you become a family,” Tarr told me. “You kinda look out for each other. When a hiker goes missing, it means a lot to hikers. And it means a lot to try to have them found — as a hiker and as a mother.”

When other searches stalled, Tarr stayed on. She grew close with O’Sullivan’s parents, and when circumstances forced them to return to Cork, Tarr stood in their stead. As a family advocate, she liaised with media, chased leads and generally kept O’Sullivan’s name in the air around Idyllwild, California.

She kept working with Con and Carmel O’Sullivan, as well as Sally Fowler. She met with volunteers and organized searches and, as word spread, those scarred by loss set out to find her. These families couldn’t take on much more, so Tarr carried it for them. Slowly, over the course of the next few years, the work coalesced into an idea: the Fowler-O’Sullivan Foundation, a formal nonprofit empowered to search for the lost.

“That total strangers go out there and search for someone they didn’t know — just because it’s the right thing to do — it’s amazing.”

There’s a mystery at the heart of every disappearance. You’ll never know exactly why someone ended up where they did. But there are clues, and with them trends. If Tarr sees a preventable pattern in Fowler-O’Sullivan’s cases, it’s day hikers encountering trouble on trail. When she goes on searches, she prepares for the worst. Her advice: Check the weather and be certain of the trail. Know when the sun sets and how long you’ll be out there, and don’t feel bad about turning around. Pack accordingly: Tarr always brings enough food and water to wait out a protracted rescue, as well as layers and a light sleeping bag. Most accidents happen when people panic. Sun setting, temperature dropping, day hikers may look for shortcuts, dip off trail, and get lost. (Through-hikers simply pitch a tent and spend the night.) It’s usually safer to stay put and call for help. That’s why Tarr always carries a satellite communicator — she uses a Garmin InReach, and the Fowler-O’Sullivan Foundation has given away 57 of them to avid hikers since its inception.

“We try to keep hikers safe — to give them information on how to stay safe,” Tarr said. “Whether they take that information, it’s up to them. But in today’s age, you shouldn’t be going missing. You should have something to send out a signal so that you’re saved.”

A search is like a stone thrown in a lake. It makes ripples for a while, but soon the water closes back. It looks as it always has, flat and still, only now the stone is drowned.

Breck Baird had a celebration of life for his mother. Afterward, he told Tarr that it didn’t feel real. He didn’t have any answers going in, and he didn’t leave with any.

Here, “closure” is something of a dirty word. Pauline Boss, the psychologist who coined the term “ambiguous loss,” calls it an outright myth. You can close a case — a material thing — but you can’t bring closure to a family. The term ties a neat bow on something that’s “messy — really, really messy,” says Maureen Trask, who runs Fowler-O’Sullivan’s support group for families of the missing. To Trask, closure suggests a finality that’s never truly there. One day, you’ll want to call for a recipe. Share a joke. See a car, unregistered, in the driveway. And a dam holding back that thing the world called “closed” will break inside your chest.

“Our grief is frozen,” said Trask, whose son, Daniel, disappeared on a hike in northern Ontario in 2011. His remains were found three and a half years later. “When someone is dying of cancer, you know where the person is, and you know that there’s going to be an ending: At some point, they’re probably going to die. With us, it’s like: They may be alive, and they may be dead. It’s a both/and situation.”

Think of it as Schrodinger’s hiker: a loved one, alive and dead at the same time.

“You know the person’s gone but you can’t wrap your head around it,” Tarr told me. “You have no answers. You don’t have a body. You don’t have remains. None of that. And you just want something back. Many families told me, ‘Even if I just had his backpack back. Something — something to let me know where he was.’ Some families hold on to the idea that they’re not dead at all. Maybe he just left the trail, and he’s fine. And I tell them to hold onto that, until they hear differently.”

People across the country rallied for Baird’s search last summer. They worked in stages. First, a team from Utah-based Western States Aerial foreran the area using drones programmed to fly a tight grid as close as they could to the treetops. They aimed to augment luck through methodology, photographing each foot of visible earth. Their drones moved like a lawnmower trimming a football field, cutting one way, sliding over exactly the width of its blade, then turning around to make an equivalent pass back the other way. The art is more in deducing the right spot to look than flying the mission, according to volunteer pilot Kent Delbon, a former national park ranger and Secret Service agent who runs drones for Fowler-O’Sullivan. It’s old-school behavioral study brought to bear on an emerging modern tool. Those photos, thousands of them, went into a folder, joining some 40,000 others Fowler-

O’Sullivan has on ice, waiting for a team of human spotters — some as far afield as Australia — to scrutinize what they held.

Someday soon, artificial intelligence may help, but for now, no program matches the human eye for spotting out-of-place items in wild places. And few eyes are as well trained as those of Morgan Clements, an early ensign to Tarr’s “image team” who has been examining these photos for nearly 10 years. Clements might identify 20 to 30 “candidate items” in every 1,000 pictures he examines. “Candidate items” are like proto-clues — unnatural objects, pieces of gear, a surprising number of mylar balloons — and those spotted by Clements have led to three bodies in the wilderness. After the drone flight, Clements and dozens like him scrutinized, inspected and debated what the photos held online, and came to a consensus on a slate of coordinates worth following up on in Idaho, a place they’ve never been.

Volunteers came to Ketchum from both coasts, spanning South Carolina to California. Bill Silliman drove up from Park City. An avid outdoorsman and photographer in his 80s, Silliman knew Baird through the Park City Mountain Sports club, an outdoor recreation group with close to 700 members. He said he had to help. He slept in his Jeep at the trailhead and hiked the mountainsides for three straight days. He was struck by how “wild” the terrain felt — rock slides, deadfall, steep and stony climbs, all just a few miles off the highway.

“It would be so easy to get off the trail and get lost out there,” he said. “And it’s the type of place you wouldn’t want to be lost.”

There’s a mystery at the heart of every disappearance. You’ll never know exactly why someone ended up where they did. But there are clues, and with them trends.

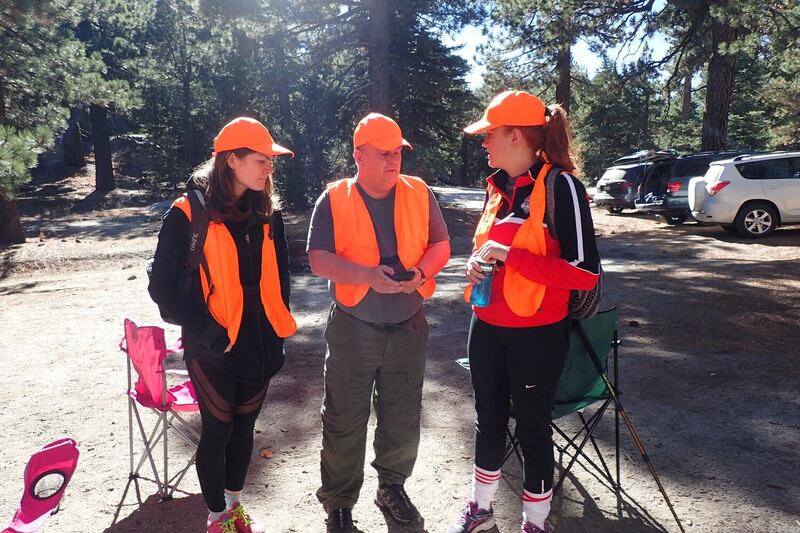

In all, 22 volunteers put on blaze orange vests and holstered radios. From the trailhead, Tarr used GPS to track them in real time. They fanned out, 10 or 20 feet apart, and raked through the undergrowth. They found animal bones, dirty underwear, rocks that looked, passingly, like skulls. Nothing belonged to Baird.

Clements remains optimistic, though four years is a long time.

“It might take multiple imaging efforts. The first set of images may not find them. A different team on a different day with different lighting and a different philosophy might show us different things. But it is true: They have to be there to be found. And we’re always guessing where they are.”

To Tarr, an empty search isn’t a failure. She’s now “95-99% certain” Baird isn’t in the area they canvassed.

“Every time we go out and don’t find her, we’ve still progressed,” she said. “You can find someone after a long time — years. It’s not as if bones, or shoes, or whatever disappear up into the air. It’s still there. We just have to find it.”

In late October, I pointed my car north on state Highway 75. It was a warm fall, and the aspens that wreathed the valley floor held themselves like torches against the blue-green spires of subalpine fir. I put my back to the Boulder Mountains, punching like gnarled knuckles through the valley floor, and took the road toward Prairie Creek. Cars sprinkled the lot. Beyond that, laughter rode the breeze down the trail. A father and his kids walked their retriever through the woods, whooping as the dog pingponged between them. Soon, the wind swept their joy into the brush, and I stepped up onto the trail. I didn’t know what I thought I’d find. But I thought of Tarr and thought of this: As long as there is something to look for, there will be someone willing to look.

This story appears in the June 2025 issue of DeseretMagazine. Learn more about how to subscribe.