One of the enduring stains on the Constitution has been what some see as its justification for slavery. But any close reading of the founding document leaves open to interpretation if the framers ever meant to legitimize slavery, at all. The preamble, after all, unequivocally states:

“We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, ... and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution ...”

The preamble clearly identifies justice and liberty as key elements of the Constitution. Exactly what justice requires and what liberty entails may be debated, but there is no question that preservation of the two is central to the Constitution’s purpose.

On the other hand, Article 4 has obscure language in Section 2, Clause 3 that doesn’t use the term slave, but the consensus among historians is that it unequivocally relates to the rendition of fugitive slaves — hence the common reference to the Constitution’s “Fugitive Slave Clause”:

“No person held to Service or Labour in one State, under the laws thereof, escaping into another, shall, in Consequence of any Law or Regulation therein, be discharged from such Service or Labour, but shall be delivered up on Claim of the Party to whom such Service or Labour may be due.”

Why did the drafters of the Constitution opt for such opaque language in Article 4? Why not state: “No slave or enslaved person in one State ... escaping into another ... shall ... be freed ... but shall be delivered up”? That certainly would have removed the ambiguity and left little room for debate. Some respond that what is opaque to us was clear to those that drafted it: Saying “person held to service” was no different than saying “slave.” Others have argued that Gouverneur Morris — a member of the Constitutional Convention’s Committee of Style — deviously altered the language at a late stage in the process to introduce ambiguity. Some have argued that the drafters made a concerted effort to avoid any reference to slavery as an institution to evade legitimizing slavery as an institution under the Constitution.

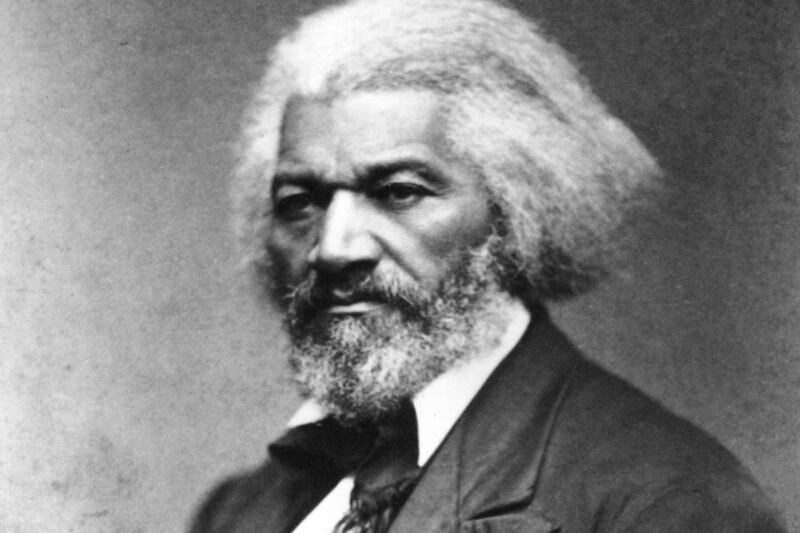

Regardless of the reason, to one abolitionist the ambiguity’s mere existence would be significant. Frederick Douglass’ life and its relation to the Constitution might be said to revolve around Article 4 and how, if at all, the preamble informs it. Douglass’ first foray with the Constitution was dark, but his view of the document became brighter with time. Once a “covenant with death,” the Constitution would become a “glorious liberty document.” For Douglass, careful attention to the language of the Constitution, its history and rules of interpretation helps tell the story of why and, perhaps more importantly, how his viewpoint evolved.

‘An agreement with hell’

Douglass was a former slave who became one of the most influential political figures in U.S. history. At the age of 20, he escaped from servitude by impersonating a free Black sailor, traveling from Maryland and ultimately arriving in New York. At this point, Article 4 became more than just words on paper. Douglass was now a fugitive slave who could be returned to servitude upon a claim made by his former owner — Thomas Auld. New York could not shield him. The Constitution provided a means for the evil hand of slavery to claw Douglass back into its vile grasp.

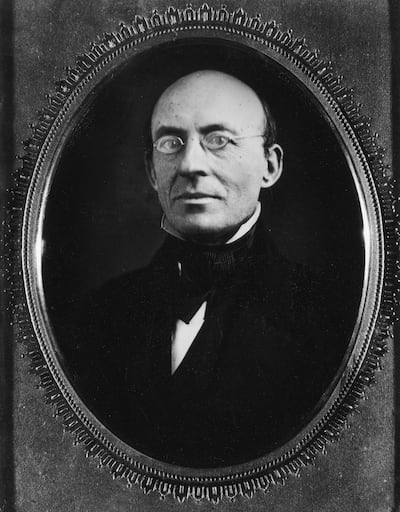

It was in this context that Douglass proclaimed: “The language of the Constitution is you shall be a slave or die.” Shortly after his escape, Douglass found himself in company with famous abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, who was known for his uncompromising moral conviction and his zealous advocacy for the enslaved. The Garrisonians, as those who agreed with him were called, had a hard stance against slavery and anything that upheld it — including the Constitution. They frequently referred to the Constitution as a “covenant with death, an agreement with hell,” and burned copies at American Anti-Slavery Society meetings.

Though the word “slave” or “slavery” never appears in the document, the Garrisonians relied on James Madison’s “Notes on the Debates in the Federal Convention, May 25, 1787,” originally published in 1840. Madison noted the drafters’ intent to protect slavery through several provisions, including: Article 1, Section 2, Clause 3 (the “three-fifths” clause); Article 1, Section 9, Clause 1 (the “slave trade” clause); and Article 4, Section 2, Clause 3 (the “fugitive slave” clause). Other clauses indirectly protected slavery, such as Article 4, Section 4 (the “Republican Guarantee” or “Insurrection” clause, which provides protection from slave rebellions, for example).

Small wonder that Douglass equated the Constitution with slavery and death. The Garrisonians had taught him that the founding document was the creator and preserver of his oppression, providing the necessary link between the North and the South that permitted Southerners to appropriate northern resources in the maintenance of slavery. They used the original intent of the drafters to make their case and were among the nation’s first originalists (more on this term later), the original originalists. Douglass subscribed to the Garrisonian position without reservation. Because of the Constitution, despite his escape to a non-slave state, he was in virtual chains.

For this reason, Douglass had a fundamentally apolitical posture toward the Union — any association with the federal government or the federal Constitution would taint the participant with complicity in preserving slavery. But Douglass could not avoid the Constitution altogether. He gained international notoriety in 1845 after publishing the “Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave,” an autobiographical account that reawakened the North (and the world) to the atrocities of slavery. Inadvertently, his notoriety put a target on his back for slave catchers, empowered by the Fugitive Slave Clause and the 1793 Fugitive Slave Act to pursue fugitive slaves in northern jurisdictions. This forced Douglass to flee to the U.K.

Douglass’ first foray with the Constitution was dark, but his view of the document became brighter with time.

Eventually Douglass would be able to return home, putting in motion many experiences that set his constitutional thinking on an irreversible path of change. After benefactors in England paid Auld to relinquish his legal claim over Douglass, he was now a free man with free ideas. He was no longer persuaded by the Garrisonian approach to the Constitution; he became convinced it was a document dedicated to freedom. Yet his conversion was not immediate. Douglass still cared significantly about the drafters and their intent, which seemed to be pro-slavery in nature.

But he became acquainted with other abolitionists who saw things differently. Gerrit Smith — who would become a longtime friend and benefactor of Douglass — believed that the Constitution was anti-slavery in character and that abolition was best achieved through political means. When Smith first approached Douglass with this anti-slavery vision, Douglass was skeptical. He could see the practical effect of adopting an anti-slavery position, to be sure. Douglass lamented the Garrisonian position, which performed the “laboring oar” in advancing the pro-slavery interpretation of the Constitution. The document did not state the word slave or slavery — it needed assistance in carrying the meaning. Why do the South’s work for them? Even so, Douglass could not abandon the history. As an original originalist, Douglass believed that historical meaning mattered in interpretation. He could not simply discredit the past in favor of construing the text for the abolitionist cause.

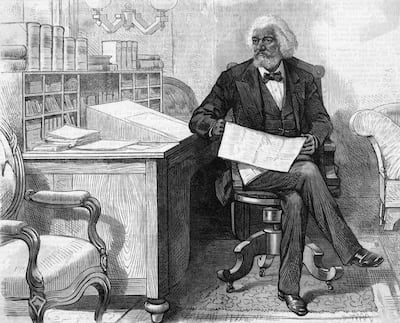

Only after careful study and investigation did Douglass satisfy himself of the anti-slavery nature of the Constitution. In May 1851, in an article titled “Change of Opinion Announced,” published in Douglass’ paper, The North Star, Douglass proclaimed that he now believed the Constitution was an anti-slavery document. He attributed his change of opinion to the study of law, government and legal rules of interpretation. (He gave specific credit to Lysander Spooner, Gerrit Smith and William Goodell.) From that moment on, Douglass argued for the anti-slavery Constitution. He proclaimed in perhaps his most famous speech, “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” that the Constitution was a “glorious liberty document.”

But what was the nature of this change? Was it merely practical or political? Or did Douglass have a serious change of heart? Certainly, Douglass’ life experiences influenced his changed position, even if only to create a space in his life where he could reconsider fundamental, theoretical questions of law and political society. But there is compelling evidence that Douglass’ new position was more than mere convenience. Tracking Douglass’ method helps illuminate how he arrived at this new understanding of the Constitution.

Humans are naturally free

To orient Douglass’ transformation in light of modern-day constitutional theory, it is helpful to say a little bit more about originalism and originalists. Originalism, put simply, is the idea that the Constitution has a fixed meaning set at the time of adoption, and that meaning constrains our understanding of it today. Where the text presents ambiguity, the interpreter uses historical meaning to provide clarity. Originalism’s methodology has changed over time, with many versions used today.

But, for purposes of illuminating its relevance to Douglass’ transformation, it is instructive to highlight originalism’s transformation from original intent to original public meaning. Original intent originalism required the interpreter to discover the original intentions of the drafters of the Constitution. What they envisioned at the Constitutional Convention controlled the meaning of the text. Similarities can be seen with the Garrisonians, who focused on James Madison’s notes to convey the proper meaning of language that might otherwise be unclear. The same can be said for Douglass’ early years as an “originalist.”

Originalism evolved, however, as did Douglass. Eventually, originalists moved on from focusing on original intent to original public meaning. The drafters’ intentions mattered less. After all, it was the ratifiers of the Constitution that gave it the force of law, and therefore it was their understanding that mattered. Rather than privilege unspoken or hidden intentions, the interpreter should privilege what the public would have understood the words to mean at the time of adoption. Douglass similarly moved on from motives or intentions kept from the public to a focus on the text that the people adopted.

He believed that the preamble clearly indicated the Constitution’s ultimate purpose: to promote justice and liberty.

What, then, of history? Many ratifiers supported slavery or at least tolerated it on some level. It would be hard to argue that the history — irrespective of what was said or not said at the Constitutional Convention — did not support a pro-slavery reading of the Constitution. Of the 13 original states, only five (Pennsylvania, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island) had passed gradual abolition statutes by the time the Constitution was ratified in 1789. It was not beyond the pale to suggest that the Constitution protected slavery.

It is here that Douglass’ interpretive method deviates from originalism, providing a new way to approach history in resolving ambiguities. This new method might be termed “natural rights originalism.” Douglass resorted to historical meaning when resolving ambiguities in the text, but he also put the preamble of the Constitution in play. He believed that the preamble clearly indicated the Constitution’s ultimate purpose: to promote justice and liberty. And the founders’ conception of justice, Douglass argued, was derived from natural rights philosophy. Natural rights are those rights every human possesses in the state of nature, before government.

All human beings are naturally free and can act according to their own desires so long as they do not infringe on the freedom of others. When they enter government, they do so based on consent. Consent is valid only to the extent that government protects the natural rights of all individuals. This basic principle immediately contradicts slavery — no human being can properly consent to involuntary servitude. The Constitution had to be read in a way that could be reconciled with its aim: natural rights. It had to be reconciled, where possible, with freedom.

While Douglass’ emphasis on history aligns him in many ways with originalists, his reliance on natural rights principles sets him apart. Like originalists, Douglass relies on historical meaning to resolve ambiguities in the text. But he acknowledges that, when looking at how the people might have understood the text, there will always be more than one plausible meaning. People read texts differently. Even more so in law, and particularly the Constitution, where it set out many principles and standards, which have much more elasticity in meaning than, say, clear rule statements. Interpreting, for instance, the scope of Congress’ powers by discovering what is “necessary and proper” is not as determinate as the requirement that the president shall be at least “the Age of thirty five years.”

To be sure, some meanings might be more plausible than others; some meanings might have more consensus or support, for instance. This is what an originalist today would do: look for that meaning which is not only plausible but has the most historical evidence of consensus among the ratifiers. Alternatively, when faced with more than one plausible interpretation, Douglass argues the interpreter must choose the meaning that best reflects natural rights principles. It matters not whether a majority preferred one reading over another. The formula for Douglass’ method was: What are the plausible readings? What is the underlying natural right principle? Which of the plausible readings best reflects the natural right? The answer to the third question provides the correct interpretation.

Interpreting the Fugitive Slave Clause provides the clearest comparison between the two approaches. Imagine the following legal dispute: Does Article 4, Section 2, Clause 3 refer to fugitive slaves? An originalist today would start with the text: “No person held to Service or Labour.” Immediately, ambiguity arises: The word slave is not to be found. A historical inquiry would reveal that persons “held to service or labour” referred to slaves; evidence from the convention and ratification debates would affirm this. Douglass, on the other hand, noted that there were other plausible readings of that phrase, such as indentured servants, for instance.

What was more, Douglass argued that a proper reading of “held” at the time meant to be under contract. And slaves, Douglass pointed out, could not enter contracts. If the natural right principle was freedom and freedom to contract, then the reading that best supported the principle was one that referred to indentured servants, not to slaves. It mattered not that the “slave” reading had more historical consensus — the alternative reading was also historically plausible, and so it governed.

Douglass used this method to answer the most critical, contentious question of his time: Is the Constitution pro- or anti-slavery? Though the stakes are not the same, the question remains a part of our discourse today. He declared emphatically that it was anti-slavery. But he did not do so naively; he had a theory of constitutional interpretation that led him to that conclusion. His method closely followed originalism but in important ways deviated from mainstream originalist methodology. Indeed, perhaps Douglass presents another way to do originalism, a way that might be more faithful to the founders’ political philosophy of natural rights.

To be clear, Douglass did not believe that one could simply import any meaning on the Constitution. He stated that if there were no plausible interpretation consistent with freedom, he would be the first to throw it out. But the preamble was clear, that justice be the aim of the Constitution. Douglass’ method reconciled the Constitution’s commitment to justice with the written words in the document.

This story appears in the July/August 2025 issue of DeseretMagazine. Learn more about how to subscribe.