Behind a plate of glass, overshadowed by the conical capsule that brought three American astronauts home from the moon in 1969, a wristwatch rests on a small stand. The command module Columbia, part of the Apollo 11 rocket assembly that Neil Armstrong and Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin rode to everlasting renown on the lunar surface, is still an intricate piece of space-age technology lined with buttons, lights, handles, hatches and an external coating of hexagon tiles, now faded a rusty orange. But the watch seems rather ordinary: white lines on a dark analog face, with a dark canvas Velcro strap.

It’s an Omega Speedmaster Chronograph, to be exact. A classic pilot’s watch, worn by the third member of that famous crew. Michael Collins never set foot on the moon; his job was to man the Columbia while the Eagle carried the others to the surface, miles below. But Collins’ path of orbit took him as far from Earth as any human had ever been. Each time the module circled the far side of the moon, the radio went dark. He was cut off from his crewmates, from NASA’s control center in Houston, from all humankind.

While his crewmates took a familiar “giant leap” into history, Collins waited. They spent 21 hours, 36 minutes in the Sea of Tranquility, as he waited, alone. I can almost picture him peering through the window and holding his breath each time the Columbia emerged from the moon’s shadow, relieved to find the sun still shining over our little blue planet, but waiting for some distant, reassuring voice to come over the radio waves. What was it like when somebody finally broke that infinite silence? “I knew I was alone,” he observed later, “in a way that no earthling has ever been before.”

That quote is immortalized on a placard near the watch, though Collins remains a supporting character in one of America’s greatest stories. On my first visit to the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C., I’m fascinated by a range of more spectacular exhibits, from the Wright brothers’ first plane to Armstrong’s moonwalk suit. But I keep coming back to the watch worn by “the world’s loneliest man.” I think about his quiet role in what we accomplished as a nation, working shoulder to shoulder for the common good, and I wonder if we’ll ever do that again.

A pull toward the unknown

Generations of American kids have dreamed of becoming astronauts and exploring the cosmos. But few were bigger space nerds than my parents, both of them scientists. We lived in South Florida, so naturally, we traveled to the John F. Kennedy Space Center at Cape Canaveral almost every year. The nation’s premier rocket launch facility covers 6,000 acres on the “Space Coast,” about 40 miles east of Orlando, with plenty of room to store certain artifacts that just wouldn’t work on the National Mall. Like the entire space shuttle Atlantis, which flew 33 missions between 1985 and 2011.

I remember stumbling backward when I tried to look up at the roof of the Vehicle Assembly Building, eighth-largest in the world by volume. It’s so big, some have claimed that clouds can form inside (this is sadly not true). I remember the Astronaut Hall of Fame. I remember The Crawlers, tracked transports that could carry the weight of 20 fully loaded Boeing 777 jets. And I remember the Saturn V rocket that hangs from the roof of the Apollo Center — the kind that powered the moon missions, the most powerful ever built. Seeing it all made space feel real to me.

A small theater there tells the story of Apollo 11, from political initiative to technological innovation and the human characters who played it out. It tells of Armstrong, gliding over the lunar surface, looking for a spot to land where he and Aldrin wouldn’t get stuck after he missed the original target. President Richard Nixon even had a speech prepared for that scenario. “These two men are laying down their lives in mankind’s most noble goal: the search for truth and understanding,” he would have said. “In their exploration, they stirred the people of the world to feel as one; in their sacrifice, they bind more tightly the brotherhood of man.”

Thankfully, the speech wasn’t needed, but the sentiment was real.

“Not since Adam has any human known such solitude.”

Humans have always felt an urge to explore, often at our own peril. Perhaps it began when we wondered what berries or game waited beyond that hill or across that river. Every mile we covered opened up a thousand more, over and over, for millennia. But what’s left for us to find? When every inch of land is mapped, photographed, scanned with LiDAR and analyzed by artificial intelligence? No wonder Captain Kirk, in the “Star Trek” TV and film series, calls space “the final frontier.” Where I grew up, there was no hope of emulating Leif Erikson, Amelia Earhart or Meriwether Lewis. Space was all we had left.

And we ate it up. Look at most any streaming service, and you’ll find a galaxy of space programming, from the romantic “Star Wars” universe to gritty dramas like “Interstellar.” But most of the genre misses the point. For their characters, space travel has been figured out, becoming about as rare as commuting to the office and about that risky, too. As viewers, we’ve come to accept space as a background, part of the scenery. But what made it so alluring to begin with was always the unknown, the danger and the selfless cooperation, sacrifice and mutual competition it took to get us off this planet to begin with.

JFK and the space race

The Communists started it. On October 4, 1957, amid ratcheting tensions in the Cold War, the Soviet Union launched an unmanned satellite called Sputnik into orbit. A month later, they sent up a stray dog drafted off the streets of Moscow — known as Laika — who died in Sputnik 2. These weren’t PR stunts. Space travel called on advanced rocket technology that could also deliver nuclear missiles more effectively. The United States had to respond, joining the space race. In July 1958, President Dwight D. Eisenhower created NASA to “carry out the peaceful and scientific parts of the space program,” per a display at the National Air and Space Museum.

But the U.S. was already far behind. The Soviets landed an unmanned spacecraft on the moon in 1959. In 1961, they made cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin the first human in orbit. NASA didn’t even have rockets designed for space travel. Even so, three weeks later, they strapped a capsule to the top of an intercontinental ballistic missile, built to deliver a nuclear warhead. In its place, Alan Shepard crammed himself into a compartment the size of a refrigerator inside the Freedom 7 — also on display — and blasted off to replicate Gagarin’s feat in May 1961.

It wasn’t enough to stay neck-and-neck. That same month, President John F. Kennedy asked Congress for funding to land American astronauts on the moon by decade’s end. Speaking at Rice University in 1962, he doubled down. “We choose to go to the Moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard.” Watching these speeches on video at the museum, I feel the same awe and inspiration I did as a kid. The message worked on Congress, too. NASA’s budget was increased fivefold by 1966. The cost of the Apollo program totaled about $25.8 billion — 10 times that in today’s dollars.

650 million people watched Armstrong and Aldrin walk on the moon. Collins was nowhere to be seen.

Cash was just a start. Massive infrastructure centers were built in Houston and Cape Canaveral, where teams of scientists, mathematicians and intrepid pilots put in the work and took the risks. On January 27, 1967, three astronauts assigned to the Apollo 1 mission were killed during a simulated launch test, unable to escape after fire broke out in the command module. They were mourned on the cover of Time magazine, and the program’s naming convention skipped to Apollo 4 in their honor. Even so, by late 1968, manned flights were inching closer to the moon every two to three months.

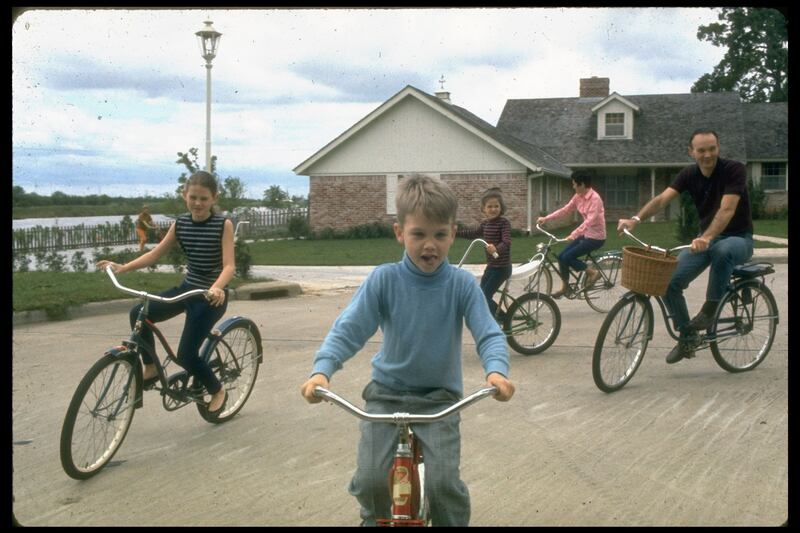

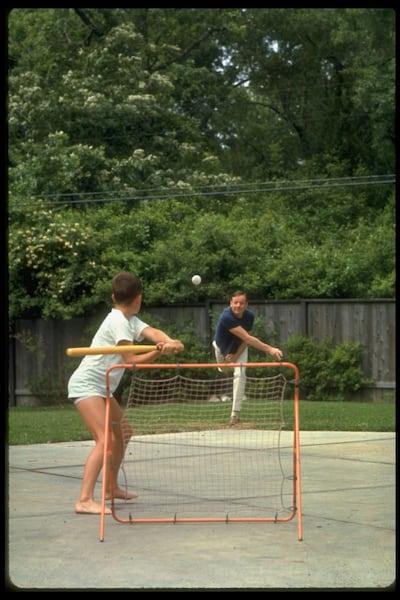

As the Apollo 11 crew prepared to make history, Life magazine photographer Ralph Morse was making them famous — and human. In his work, Armstrong plays baseball with a son and reads the paper over dinner, getting home too late to eat with his family. Aldrin keeps it professional, posing in a jumpsuit by a model of the moon. Collins rides bikes with his three kids, paints at home and reads paperbacks at a beach with his wife. These images — some published then, some decades later — bring home what these ordinary men were willing to risk for love of country and to see what was around the bend.

‘Not since Adam’

When Armstrong and Aldrin took their first steps on the moon, about 650 million people around the world watched on TV and heard Armstrong’s iconic narration of a truly unique accomplishment. Collins, as we know, was nowhere to be seen. But an American flag was planted on the surface, a Cold War victory that the Soviets never matched. Back on Earth, they took a 38-day celebration tour, visiting 24 countries. As one display at the museum notes, “people worldwide looked upon the first moon landing as a human achievement, not just an American one.”

If Morse made the astronauts celebrities, their journey made them heroes. “People enjoy being amazed, and space exploration never fails to deliver,” writes Andrew Chaikin via email. The author has largely dedicated his career to chronicling the Apollo era. It’s not just about discovery. Unmanned missions and space telescopes have delivered crystal-clear portraits of Pluto, snapshots of distant nebulas and video of the sunrise on Mars. But this was different, because they went there. “When astronauts are the ones seeing new things, it’s all the more compelling, especially when they come home and tell us about it.”

The space race was won, but politics never sit still. “Space was no longer the priority,” Chaikin says. A year later, “NASA was struggling to keep its human spaceflight program alive in the face of budget cuts and political opposition.” It’s easy to forget that as many or more Americans opposed government funding for trips to the moon than supported it. Even the museum admits that “many citizens marveled at the achievement but questioned the billions of dollars it cost.”

Each time he circled the far side of the moon, he was cut off from his crewmates, from Houston, from all humankind.

Even so, the museum is less a record of the journey than a shrine to its memory. Flags are draped everywhere, and placards speak of a nation pulling together to achieve something extraordinary in a violent and unsettled age. “We’re drawn to experiences that aren’t universal, that represent the farthest edge of what humans can do,” Chaikin says. “We’re compelled by ‘firsts,’ by extremes, by frontiers. The moon missions fit all three.”

We also remember the little things. Like the miniature harmonica and six small, silver bells that the two-man Gemini VI-A crew smuggled aboard just before Christmas 1965, which they used to play a surprise rendition of “Jingle Bells” for their counterparts back in Houston. There’s also Collins’ checklist for an earlier mission on Gemini X, citing the necessity to “prepare waste jettison bag” — another reminder that this was a human endeavor after all. And that brings me back to his watch.

At first, I was fascinated, but perplexed. Like looking at a piece of abstract art, I knew it meant something but couldn’t put it into words. Then, on my way out, I saw the original model of the starship Enterprise, from “Star Trek.” That series depicts a utopian future for humanity, beyond war and even currency. “We’ve eliminated hunger, want, the need for possessions,” says Captain Jean-Luc Picard, played by Patrick Stewart, in “Star Trek: The Next Generation.” “We’ve grown out of our infancy.” In creator Gene Roddenberry’s idealistic vision, humans are united in their quest for knowledge and the mysteries of the universe. In reality, the Apollo program may be the closest we’ve ever come to that.

The Enterprise model is a prop, like the life-sized X-wing fighter from the original “Star Wars” trilogy that hangs from the rafters nearby. Both look cheap and uninteresting compared to the real deal, though we spend far more time as a society visiting their fictional worlds. Meanwhile, profit, rather than idealism, motivates the private companies that launch most space missions in the news today. Down the hall, the “Futures in Space” exhibit remains under construction. But that wristwatch is real and tangible. It accompanied a man who truly went where no man had gone before.

“Not since Adam has any human known such solitude,” observed one mission control official. And out there, the watch tethered him to his home and our place in the cosmos. In outer space, where days are not days as we know them, and time itself can be warped by mass and energy, the watch kept ticking. Second by second. Collins was less philosophical about it. Reconnecting with mission control, he said, was unremarkable. He spent his time alone listening to music and looking out into the void of space. He was comfortable. The idea that he felt existential loneliness or yearning for the voice of mankind was, simply, “baloney.” The watch doesn’t disagree. Collins was a man, and nothing more, it tells me, who just happened to redefine the limits of our existence.

This story appears in the July/August 2025 issue of DeseretMagazine. Learn more about how to subscribe.