Gaggles of giggling girls (and a few fine gentlemen) joined together in cinemas across the world this past April.

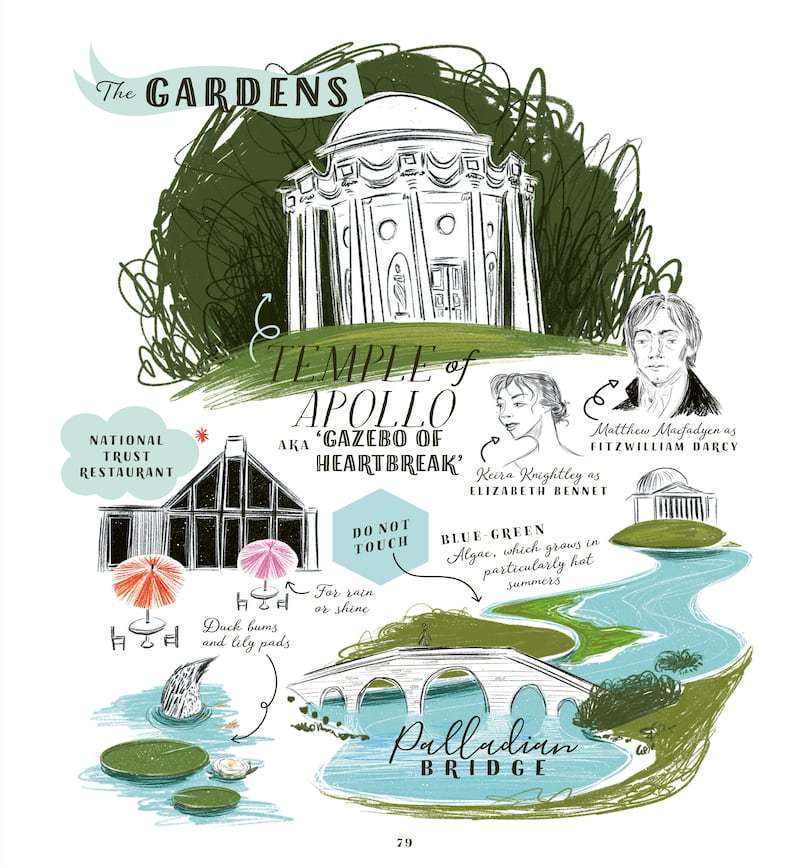

Some sported bonnets, others toted buckets of popcorn, and all were there for one reason: to witness “Pride and Prejudice” on the big screen. Only this wasn’t a new adaptation of Jane Austen’s best-known work, it was a rerelease of the beloved 2005 film starring Keira Knightley as Elizabeth Bennet and Matthew Macfadyen as Mr. Darcy. This 20th anniversary screening grossed $7.5 million globally and played in nearly 1,400 cinemas — a fitting birthday gift for Jane herself, born 250 years ago on December 16, 1775.

From Hollywood to Bollywood and on both sides of the Atlantic, Jane Austen has captured the hearts and minds of millions. The ongoing accessibility to her stories through repeated adaptation has contributed to her lasting legacy and success. With a new “Pride and Prejudice” series in the works at Netflix and dozens upon dozens of adaptations and derivative works to return to, Austen has never been bigger. In the U.K. alone, Austen’s sales are spiking. At least 78,000 copies of her books have sold there in the first half of 2025, up 14,000 over all of last year, and the highest sales since 2009, when BBC aired an adaptation of “Emma.” In the U.S., a new illustrated “Pride” appeared in the top 10 young adult books throughout the summer, according to the American Book Sellers Association.

After centuries of rapidly evolving societal change, why does Jane Austen still draw such a crowd? Any sincere attempt at answering this question acknowledges a host of potential reasons. Firstly, Jane Austen’s words, while rooted in a 19th-century lexicon, continue to provide incisive commentary on the human spirit. Her observations, often filtered through the voices of her characters both sardonic and naïve, expose a world of money, love, social class and propriety.

Austen writes in “Emma” that “human nature is so well disposed towards those who are in interesting situations, that a young person, who either marries or dies, is sure of being kindly spoken of.” It is no wonder that in Utah, the state with the highest marriage rate, readers and moviegoers are particularly drawn to Austen’s œuvre. “Austenland,” directed by Utah-based Jerusha Hess, maintains a local cult following on par with “Napoleon Dynamite” (directed by Hess’ husband, Jared). The Jane Austen Society’s Utah chapter hosts birthday luncheons and lectures. And Janeites relish Regency retreats, trivia nights and dance societies statewide.

The marriage plots in her novels often center tensions over class, social standing and sources of wealth, while today’s young adults also face questions about religious duty and expectation, emotional preparedness and commitment. But undergirding both the 19th- and 21st-century anxieties about marriage is the same question: Does love conquer all?

Although romantic plotlines have existed since ancient times, the popularity of and demand for such stories has grown exponentially in recent years. Austen made the enemies-to-lovers trope what it is today with Elizabeth and Darcy, and some of the most sought-after romance books and movies now follow a similar arc. For those who seek out clean and wholesome literature, where better to turn than the chaste social mores of Regency England?

A lifelong companion

I grew up alongside the BBC “Pride and Prejudice” miniseries, which first aired in the U.S. in 1996 when I was six months old. My mom’s love of the adaptation carried her through subsequent pregnancies, with me by her side. My first memory of my parents being away was for an early anniversary trip to England. The photos and tales of these adventures sowed the seeds for my future affinity for the British Isles and its literature.

My own “Juvenilia,” as Austen’s early works are called, is contained in a plastic pink notebook with highlights such as family tales, detective notes from mysterious elementary school goings-on, and my imagination of a future life as a gainfully employed adult. Now armed with a job and a computer, my writing follows similar themes, with its settings and dreams altered for my present circumstances and broader worldview.

As a teenager, I read Austen’s most popular works, “Pride and Prejudice” and “Sense and Sensibility.” Around the same time, a church leader gave each teenage girl in my congregation a “Jane-a-Day” journal with her quotes on each page and a place to write each day for five consecutive years. Coming back to her words daily made me more aware of Jane’s wisdom and wit, something I’ve always admired.

My high school years saw me poring over the YouTube series “The Lizzie Bennet Diaries,” my college years introduced me to “Persuasion” on study abroad in London, and suddenly I was feeling a pull to be in England as often as I could.

Austen’s words, while rooted in a 19th-century lexicon, continue to provide incisive commentary on the human spirit.

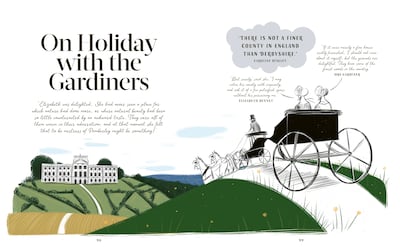

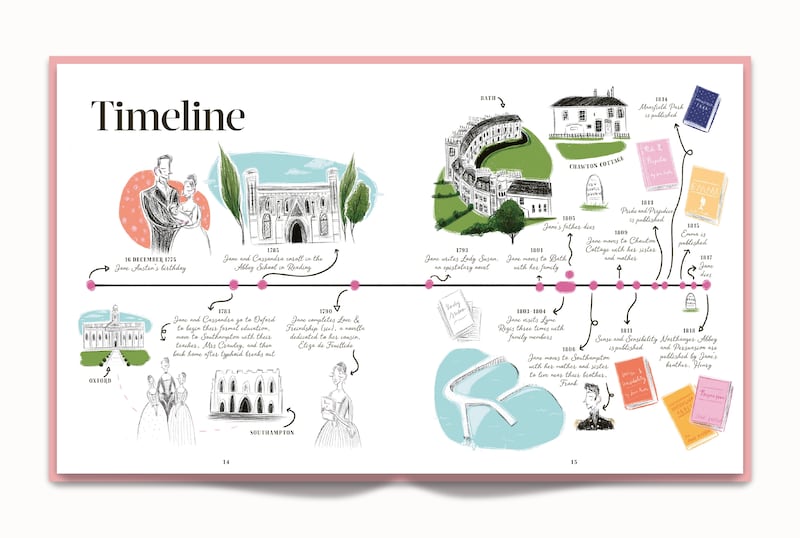

In late 2017, I was contacted by illustration students during my junior year at BYU to participate in a grant-writing project that would eventually lead to the creation of the book “Jane Was Here: An Illustrated Guide to Jane Austen’s England.” In preparation for creating this guide, I spent the following summer dedicated to everything Jane Austen, diving into each of her novels, reading all I could about her life and watching every screen adaptation I could get my hands on. After researching on paper, the time came to hit the streets for the thousand-mile road trip of a lifetime.

As I navigated the winding narrow roads of the English countryside with my friends, we fell in love with Jane and her characters all over again. Walking in Jane’s footsteps and through the backdrops of the movie sets based on her work made her all the more real to me. Her home in the small Hampshire village of Chawton, now the Jane Austen’s House Museum, features a humble writing desk, less than 18 inches across. At this table, Jane began to experience professional success, and with it, a degree of independence that allowed her to seek publication for her work more productively.

She made the enemies-to-lovers trope what it is today, and some of the most sought-after romance books and movies now follow a similar arc.

Later, in 2020, I had the privilege of seeing “Jane Was Here” on store bookshelves. Seeing my name on the cover of a book I wrote at a portable digital desk smaller even than Jane’s dodecagonal walnut one was a profound experience, in no small part due to the legacy Jane Austen left. As an unmarried woman who died fairly young in a time when women had little power, Jane transcended the boundaries set for her, both systemic and implicit.

When people sing “Happy Birthday” this December for a woman who has laid at rest in Winchester Cathedral for more than two centuries, they are honoring the endurance of storytelling and the power of words. Her name is a reminder that women’s voices and experiences matter. And that maybe love, in all of its complexity, is worth fighting for.

This story appears in the December 2025 issue of Deseret Magazine. Learn more about how to subscribe.