This is not how the digital age was supposed to look. A tall, bearded photographer fusses with a large camera mounted on a tripod, with rubbery black bellows like an accordion, adjusting for the light in the room and the distance between the lens and his famous subject. “This is a process,” explains Carlo Alberto Orecchia, “but it’s worth it.” The subject, an elderly man with long white hair, is Keith Richards, lead guitarist of the Rolling Stones and the actor behind Captain Jack Sparrow’s father in the “Pirates of the Caribbean” movies. “High tech, old style,” says Richards, clad in mint green and a black velvet jacket, filling the awkward moments as he waits beside a grand piano.

Whenever he can, Orecchia shoots on film. He loves the visual texture of prints made from negatives, compared to the sterile perfection of digital images. Besides, there’s a meditative quality to the process: visualizing an outcome, bending the light to capture it, developing the negative and making prints in the darkroom, with a careful dance of chemistry. And there’s demand for it. Based in Hollywood, Orecchia has shot film portraits of actor Clint Eastwood, director Quentin Tarantino, and musicians from Dolly Parton to Bruce Springsteen, among others. “OK,” he announces. “Three, two, one.” Click.

Photography was synonymous with film. Until it wasn’t.

These days, Orecchia is not alone. Two decades after technology seemed to signal the demise of film, this old medium is experiencing a quiet resurgence. It can’t replicate the utility of digital cameras, with their stunning shutter speeds and embedded editing software, as handy as the phones in our pockets. Digital makes it easy to document a family dinner or post an old dress on eBay. But when artistry is the goal, a growing market of young photographers is reaching for good old-fashioned film.

The camera clicks and whirrs. “One last one,” Orecchia pleads, swapping out the cartridge and reframing for a close-up on Richards’ craggy features. An assistant offers to adjust the tripod and Richards plays along. “No, let me do that for you,” he says, his rasp devolving into a chuckle, then a cough, the moment captured during the filming of a documentary in New York City in 2025. His time with Richards is running short, but Orecchia trusts his medium.

Three, two, one. Click.

Photography has always been intertwined with technology, as rooted in science as it is in the arts. The first known camera obscura, a dark room where light passing through a small aperture projects an inverted image of the outside world onto the opposite wall, was built around 1000 C.E. by the polymath Alhazen, who used it to view an eclipse in Cairo, Egypt. His writings on optics inspired European thinkers like René Descartes, Johannes Kepler and Leonardo da Vinci, who famously relied on a camera obscura in his art. Cameras still operate on the same principle, much like our eyeballs.

By the 18th century, inventors were experimenting with photograms, ephemeral images captured on beds of chemicals or minerals that would inevitably disappear. But it was in 1826, when a Frenchman named Nicéphore Niépce captured the first fixed, permanent image on a substrate of pewter coated with bitumen, that photography was born. Niépce died in poverty before his invention became a commercial success, but a colleague named Louis Daguerre carried on his work. In 1839, Daguerre introduced the world to the first mass-produced camera and a process called the daguerreotype, which stored images on sheets of copper, showing his works to the French academies of science and fine arts in Paris.

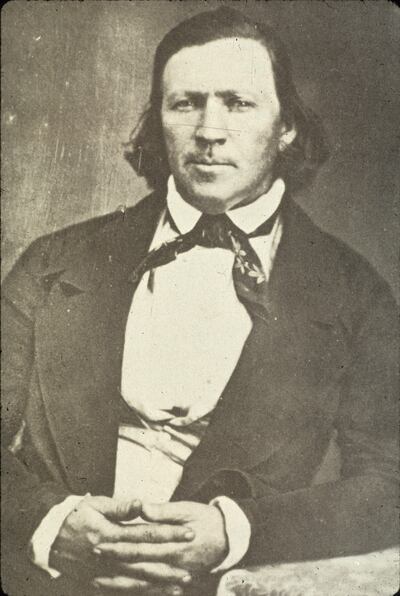

The new medium was largely seen as a tool of record, useful for documenting still subjects like buildings and patient individuals like Andrew Jackson and Brigham Young. One show at London’s Crystal Palace in 1851 drew such a crushing review against the idea of photography as art that its creator pivoted to a career in the portrait studio — now a well-trod path. The art form largely developed outside the public eye, among dedicated photographic societies and Victorian-era hobbyists who didn’t need the money, like Lewis Carroll, author of “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.”

The advent of the ambrotype disrupted the market in the 1850s, recording images of stunning clarity on glass plates known as “collodion positives.” Surviving examples include portraits of Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass. That process was outpaced a decade later by the “tintype,” an errant allusion to its reliance on thin iron plates. Cheaper, faster and better suited for a journey by wagon, tintypes preserved images of common soldiers in the Civil War, tourists at seaside resorts and even Old West outlaws like Henry McCarty, also known as “Billy the Kid.” In the same era, paper prints made photographs both portable and shareable.

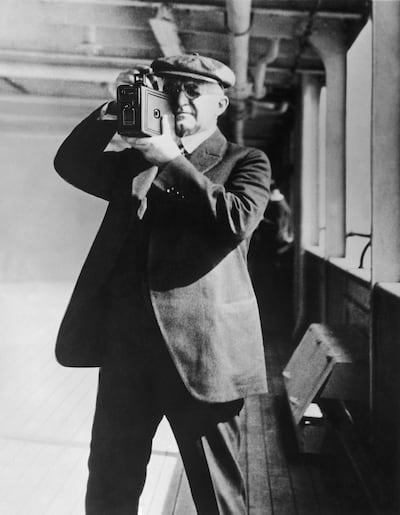

All these processes required unwieldy devices and long exposures, leaving little room for spontaneity or expressiveness. That started to change in 1888, when George Eastman released the “Kodak,” a made-up name for a hand-held box camera that captured negative images on paper or celluloid strips covered with a light-sensitive emulsion: film. That camera was a luxury item, but in 1900, his Eastman Kodak Company followed up with the “Brownie.” This simple, reloadable camera sold for $1, taking photography to the masses.

Soon Brownies were everywhere, and so were photographers. Soldiers carried Brownies at the front during World War I. The daughters of Russia’s last czar used Brownies to document their ill-fated lives. Even the iceberg that sank the Titanic in 1912 was later photographed with a Brownie. In 1916, a California father gave one to his 14-year-old son, Ansel Adams, during a family trip to Yosemite National Park. That inspired his lifelong pursuit to not just master the medium but expand its capabilities, beyond capturing to creating the images he wanted, using dark room processes the way a painter would use a brush. Few doubted whether it was an art form anymore.

A global industry boomed across the 20th century, producing cameras of all sizes, technical capabilities and price tags for every kind of photographer. Families documented summer vacations and holiday dinners with Polaroid instants, Kodak Instamatics or other one-click cameras easily loaded with 110 cartridges they could get developed at drive-thru booths. Professionals shot street scenes with Leica Rangefinders and football games using powerful zoom lenses attached to 35mm Nikon SLRs, which offered extensive technical control. Fashion-centric artists refined portraiture, using artificial lighting and larger negatives to capture the detail required for magazine covers and gallery reproductions — like Annie Leibovitz with her medium-format Mamiya RZ67 or Richard Avedon with his large-format Deardorff.

Photography was synonymous with film. Until it wasn’t.

“Film Is Not Dead,” reads a black sign emblazoned across the façade of a white brick storefront in downtown Provo, Utah. The message is not subtle. Purple neon in the window directs passersby to “Buy Film Here.” Inside, shelves behind the front counter are stacked with rolls of film in little boxes like it’s 1989: Kodak, Ilford, Fujifilm, CineStill. Blue neon hangs overhead repeating the mantra: “Film Is Not Dead.” Then there’s the business name: theFINDlab. Guess what F-I-N-D stands for? It’s either wishful thinking or commitment to the bit. Unless they’re right.

It’s a digital world now, isn’t it? Kodak tried to keep up by making its own line of digital cameras but filed for bankruptcy in 2012. Its perilously close again after accumulating $477 million in debt, but don’t miss this detail: half of the company’s film manufacturing team was hired within the last three years to meet rising demand. Elsewhere, Ricoh released the Pentax 17 last year, the first new film camera from a major brand in two decades. The global market for film cameras is now expected to grow by 5 percent annually, reaching more than $387 million by 2030.

On a smaller scale, theFINDlab develops 500 to 600 rolls of color film every day at its mail-in processing facility in Orem, where dozens of Gen Z and millennial film aficionados work to develop, scan and edit images. Foot traffic at the Provo location, or “analog community center,” seems to back that up. Here, they can test out cameras, buy photography books, rent time in a dark room or a studio bathed in natural light, and even display their work in a small gallery. A warehouse space behind the shop hosts classes and other events.

Jonathan Canlas started the company as an offshoot from a workshop with the same name, and still sees education as central to its mission. There are even tutorials online, like Shooting Film in Snow or How To Capture The Perfect Christmas Morning on Film. A certain how-to component is necessary in an age when people are used to cameras that do the thinking for them. The basics of film photography can seem arcane, but that’s often the point. Above all, film requires attention to detail. A standard roll of 35mm film has an average of only 24 to 36 photos, so there’s no freebies and few opportunities for do-overs. “It forces you to be present,” Canlas says.

In the darkroom at theFINDlab, Portia Rowbury carefully holds a film strip by the edges and slides it into an enlarger. The projector device flicks on with a white flash, casting a light against the light-sensitive photographic paper on the table below. She watches the paper and waits, her five-panel hat and dark brown ponytail tinged red in the dim glow of the lab’s safelight. After about 10 seconds, she can faintly see the black-and-white image emerging. Behind the oversized prescription lenses of her wire-rimmed glasses, her eyes light up.

Being able to come back to something that you can hold in your hand is a real, powerful thing that we can’t underestimate.

Though she also works as a wedding photographer, this is just the second time Rowbury has developed her own prints. But there’s more to this particular process than novelty. Last summer, a week before she gave birth to her first child, her cousin took his own life. In grief, she found herself replaying one of her last conversations with him, about how people say that fish don’t feel pain when in fact they do, how dads hide that difficult reality to spare their children’s feelings while fishing. More than ever, she wanted to be present. So she turned to film, working on a photo series she calls “Fish Don’t Feel Pain.”

The sound of running water echoes off the walls as she moves the photo paper to a developer bath and sloshes it around. “You have to agitate it to make sure that the chemical covers the whole surface,” she says. She continues to stir for two minutes straight. The bath smells faintly of vinegar or ammonia. Then, as if out of thin air, her son’s tiny legs materialize in little jeans beside a couple of small fish. Once she’s sure the hues are as dark as she wants, she moves the print to the fixer bath, which stops development.

“Art is a cool way to process things, to make something sad or ugly into something beautiful that you can then feel a little bit of peace about,” she says, moving the paper into the next bath, which makes the picture permanent, before a final rinse. “There’s also something fun about not knowing what your image is going to look like until later on.”

After making sure the print is clean, Rowbury scrapes off the liquid, steps out of the glowing red room into harsh fluorescent lighting, then sets her photo on the drying rack, still damp and glistening.

If the idea of film seems nostalgic, that may be part of the charm for people who’ve grown up in an age where everything is available all the time, but nothing ever seems to last. “Underlying this entire conversation is the desire to hold something in your hand, to have that artifact that’s going to possibly outlive you,” says James Swensen, a professor of art history and the history of photography at Brigham Young University. “As artificial intelligence and all the digital things force us into these other realms, being able to come back to something that you can hold in your hand is a real, powerful thing that we can’t underestimate.”

In an age when people are used to cameras that do the thinking for them, the basics of film photography can seem arcane, but that’s often the point.

Film is an inherently imperfect medium, with flaws built into the materials, the machinery and the people using them. Historically, serious photographers have worked deliberately, relying on math and chemistry and projection to craft the images they envisioned. But for those accustomed to seeing the finished product on a screen before they even click the shutter, the idea of guessing at the outcome — and the potential element of surprise — is entrancing.

Old cameras “require you to think it through, to do a little guesswork and to record not knowing instantly what you’re going to get,” Swensen says.

Orecchia learns that lesson after his shoot with Richards. In the rush, he accidentally reloaded the same film. But the resulting double exposure, also in black and white, produces a remarkable image. Richards sits on a piano bench, straight-faced and lax with his hands on his knees. His close-up is superimposed, magnifying the white tufts of hair that poke out of his black cap, and the hard-won grooves around his cheeks and eyes — encircled with his characteristic eyeliner. His polka-dotted scarf contrasts in texture with the Persian rug under his feet. A light leak adds a kind of auric quality, but the film is what brings it home.

“The thickness and the three-dimensionality of the silver grain and the way that magical chemistry helps tell a story, because it’s not just a flat image, it’s a three dimensional-experience,” Orecchia says. “It’s an energetical thing that I feel is really entangled in the negative.”

This story appears in the December 2025 issue of Deseret Magazine. Learn more about how to subscribe.