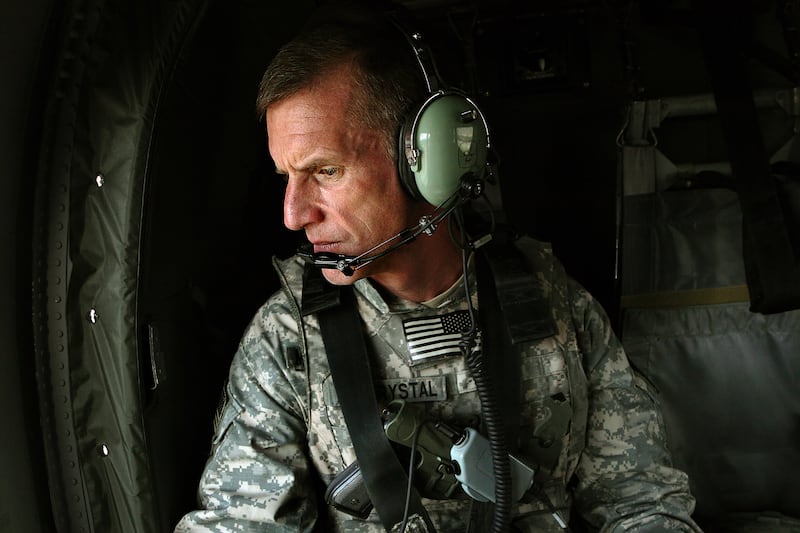

If I’m ultimately buried at Arlington National Cemetery, my grave, by regulation — and just like my father’s — will be marked with a 13-by-42-by-4-inch white marble headstone, upon which a maximum of 11 lines of text will record my name, dates of birth and death, military service, final rank and perhaps the wars in which I served. On the other side will be my wife’s name and the dates of her life.

Those lines are not much to record the essence of who we were, but they aren’t intended to. That reality, more difficult to define, cannot be recorded in dates, accomplishments or even perceived successes and failures. It is found in our character — the most accurate, and last full measure, of who we choose to be. Every other metric is superfluous.

Character, the appropriate destination of our life’s journey, is not a trait inherited at birth or a gift from a learned mentor. It does not automatically come from education, position or experience. Character, instead, is a choice. It is built upon the convictions, or deeply held beliefs, that we embrace and the discipline we muster to live up to them. Despite its deeply human nature, it is curiously mathematical: character = convictions x discipline — meaning, if we lack either substantive convictions or discipline, the resulting product (our character) lacks all value. It is as simple and as thunderously consequential as that.

Through a fascinating, and sometimes tumultuous, military career and all of life before and after, I’ve reached a set of convictions that serve as the load-bearing pillars of who I am. And to the extent of my personal discipline to live up to them, they define my character. Candidly, neither my convictions nor my character are all that they could be, or even all that I wish they were. But they remain a work in progress that can still improve, and they benefit from my attention. When I remember to challenge my thoughts or actions against the standards of the character I aspire to, I am better for it.

A test of conviction

The ranger was limping. We were about 20 miles into a forced march carrying weapons and heavy rucksacks, and the hike seemed to engulf and overwhelm the young man’s small frame. It was peacetime, before the post-9/11 years of war, but soldiering still held many of the traditional pains.

When we briefly halted, I asked the ranger to remove his jungle boots so I could check his feet, expecting a blister or two we could informally treat before it was time to move again. Instead, the ball of his left foot was covered with a red oval larger than a silver dollar, the skin scraped completely away, leaving a deep divot, as though a chunk of his callused foot had been carved out with a dull knife. Just looking at it made my stomach turn — walking must have been excruciating.

I went to find a nearby medic to tell him we’d leave the ranger in place for later evacuation. But when I turned back, the man was already retying his boot, clearly committed to continuing. Looking at me with a determined stare, he simply said, “Recognizing that I volunteered as a ranger ...” and continued to recite the first stanza of the creed we all lived by. Less than 19 years old, less than a year in uniform, and less than 160 pounds soaking wet, this young man had made a decision of personal conviction. In that instant, he embodied the character I admired and envied.

Life, I’ve learned, is mostly about who we decide to be. There are variables we don’t control, such as the physical traits we inherit and many of the circumstances surrounding us. But what and whom we choose to believe in, and how those beliefs shape our character, is up to us.

It is not when or where we live, but how we live. The score reflects a game’s outcome, but the manner of play defines its quality.

We often talk about character, but it’s elusive. The combination of behaviors, motivations and bedrock values that reflect some intangible essence of a person are difficult to assess. And yet, ultimately, character is what matters most.

We tend to bemoan a shortage of character in those with power, money and celebrity. But we still willingly give them our votes, money, social media likes and attention. We are vaguely aware that the soaring ideals of heroes and philosophers differ markedly from those of our daily experience. But we don’t think too deeply beyond that.

Character, when we need it most, is seemingly nowhere to be found. At the same time, we’re uncomfortable proclaiming its death. Faced with an often frightening world, we at least want to believe the combination of attributes and behaviors we call “character” are still important — perhaps more than ever.

So, what is it?

Character has long been the subject of serious thought. Marcus Aurelius identified it as the sum of your thoughts, feelings and actions over time. It is who you are and the only thing you truly own. It both defines and is defined by what we do. But it is also something greater than the sum of our actions.

Life is mostly about who we decide to be. There are variables we don’t control, but what and whom we choose to believe in, and how those beliefs shape our character, is up to us.

Reflexively, we think of character as something good. A person of character is most often assumed to be one of strong, admirable values and positive intent. But if character is what we do, we know from experience that it can have a dark side. A person’s character can faithfully reflect evil as easily as it can good.

It can also be conflated with strong faith or unwavering adherence to ideas, ethics and values that may or may not be good. One person’s fanatical suicide bomber is another’s martyr. There’s room here for honest argument, but character that is closed to differing perspectives is problematic. We tend to salute the individual who suffers, even dies, for what they believe, but what if their beliefs are ones we abhor? It is not so easy then.

Still, I most often consider character in the positive. If I describe someone as a person of character, I typically mean they represent values and behavior I respect and admire. But I’ve also come to separate character from intellect, charisma, courage and countless other qualities. Individuals of seemingly endless talent and impressive achievement can be vessels empty of the character I consider important.

Contemplating character is helpful to understand what other thoughtful people have concluded. Aristotle connected character with virtue, celebrating those who could maximize their virtues — which he defined as courage, justice, prudence and temperance — while limiting their vices. Confucius extolled wisdom, benevolence and courage, and identified the principle of ren: a combination of compassion, empathy and humanity.

The Enlightenment produced some of character’s most familiar analyses. Immanuel Kant held the individual responsible to invoke reason, rationality and a respect for humanity. More than a century later, Jean-Paul Sartre continued a similar theme, focusing on a person’s free will and personal choice in defining themselves. Who we are, they reasoned, is largely who we choose to be.

Friedrich Nietzsche, famous for his statement “That which does not kill us makes us stronger,” reflected a more cynical view. Strength and personal will, he reasoned, were necessary to overcome challenges and formed the bedrock of a strong individual.

Individuals of seemingly endless talent and impressive achievement can be vessels empty of the character I consider important.

The more recent experience and later writings of James Stockdale connect on a strikingly visceral level. The naval aviator’s seven-year brutal captivity in North Vietnam, recorded in his frank description of both human frailty and stunning strength, brings the concept of character into sharp, sometimes frightening focus.

Stockdale found character anything but the product of serendipity or fate. “I think character is permanent, and issues are transient,” he said in a PBS interview in 1999. Virtue was an essential part of character and critical to society, he felt, writing in “Thoughts of a Philosophical Fighter Pilot”: “Those who study the rise and fall of civilizations learn that no shortcoming has been surely fatal to republics as a dearth of public virtue, the unwillingness of those who govern to place the value of their society above personal interest.”

Our journey to character is not a simple one. We should mine the wisdom and experience of others, but ultimately, defining character and charting our journey is up to us. We must examine ideas and develop convictions that become a mirror of our soul and a lens through which we view life — then use them to create the person we’d like to be, and attempt to be that.

Put even more simply, it’s a choice and a discipline.

Lessons from a lifetime

I’ve spent a lifetime studying leaders, heroes and scoundrels, with more than a few individuals who are justly categorized in all three groups. We seek to define each person’s character so that we can venerate or denounce them, but in most cases, cleanly defining who a person is proves elusive. Many of us struggle to know what even our own character is.

This raises the obvious question of whether character is real or a useful construct to advocate for selected values and behaviors. Many of us profess faith in things we can never confirm, like miracles, but we accept them anyway. Could character be the same? Might what we venerate, the bedrock of values supporting a superstructure of worthy behaviors, be nothing more than an ideal? Is it dead, dormant or simply difficult?

I was blessed to have loving parents of admirable character, mostly good sports coaches and some excellent military commanders. I was exposed to decades of values-oriented education and training. Raised in an era when even my elementary school unabashedly advocated for patriotism and ethics, then molded at West Point through a narrative of service, discipline and an unequivocal honor code, I wouldn’t have been able to dodge thinking about character.

Then there was the real world.

We’re all unsurprised when people we don’t respect validate our estimation of them by being dishonest, disloyal or selfish; it’s strangely satisfying to both be right and feel morally superior at the same time. We’re also disappointed when leaders we esteem prove all too human and friends, family and teammates fail to live up to the standards we’ve hoped for. We make excuses for those we love, but when they deviate from what we expect, it hollows out our faith in their character.

Hardest of all is when we see this lack in ourselves. No doubt there are people who celebrate their ability to circumvent or undercut laws and norms, but most of us hope not to be that way. Still, in moments testing our integrity, compassion and commitment to things we’ve embraced, most of us remember when we were not the person we’d hoped to be — when our ambition, ego, impatience and greed led us to act in ways we might describe as “out of character.”

But maybe the question is whether this is just our real character revealed. Nothing hurts quite so much as admitting we’re not the person we claim to be.

If we watch people of poor character win elections, accumulate riches or achieve unprecedented popularity, the obvious question is whether character ultimately matters — and did it ever? It did. Or at least, so we said.

Regardless of what they say or write, the people of every era consider themselves less worthy than those who came before. Reading literature, admiring architecture or squinting in the sunlight at imposing statues of intimidating personalities of old, we believe “they” were wiser, braver and better than we are now. Explorers, inventors, queens, soldiers and all those who shaped their respective epochs had character. We stand in reverence of Tom Brokaw’s “Greatest Generation” and admit that we’re unsure we could, or would, do the same today.

We have reason to feel this way. For centuries, we’ve told stories, painted pictures, written poetry, and sung of men and women of character. As a child, I was told young George Washington could wield an axe well enough to cut down a cherry tree but was incapable of lying about the deed. We are long haunted by the shadow of our forebears.

Our fascination with character is more than idle celebrity worship. There has always been an intuitive understanding that life in the world, as English philosopher Thomas Hobbes described it, could be “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.” Incentives abound to reward power and wealth, while only a fragile web of ethics, values and social mores — often connected to religion — reinforces concepts of justice, mercy, generosity and benevolence. Without the pull of character on a person’s conscience, things could be a lot worse.

In the past, people were expected to behave with admirable character, even if only superficially. Integrity was openly demanded and countless duels were fought over questions of honor. Newspapers and pamphlets routinely charged prominent people with misbehavior and the articles were reliably followed by strident denials and counter-accusations. America’s Founding Fathers — a gifted but often thin-skinned collection of patriots — claimed to be guided by an ideal of character but also masterfully constructed a system of governance that accounted for a lack of it.

In most ways, the innate character of our ancestors differed little from our own. The world knew cruelty, greed and hatred in doses we can scarcely comprehend today, and they constructed an imperfect but still valuable latticework of rules, norms and ideals that sought to control things as best they could.

Character has never been perfect. Heroes were often also slaveholders, philanderers or crooks. But there was an understanding that while we could pretend not to notice those misdeeds and shortcomings, it was essential that there be a standard. We might rarely, if ever, embody the ideal of character, but some set of benchmarks should enact a gravitational-like pull to a higher plane. We may periodically be despicable, but we should feel guilty when we do. That is the importance of character.

Superficial talents or qualities can confuse us about who a person really is, even when we are that person. Character is revealed and sometimes shaped by situations, especially when we must make fundamental choices about right and wrong, obligation over advantage, and courage over cowardice.

The West Point Cadet Prayer captures the essence of behaving as we should, regardless of the costs: “Make us to choose the harder right instead of the easier wrong, and never to be content with a half truth when the whole can be won.”

A final reflection

Depending upon the weather, the gathering may be quite small. But I’m sure to be on hand. The day of my funeral — hopefully some years in the future — along with that of my birth on August 14, 1954, at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, will bookend my life.

Finally, there will be no more early-morning workouts, sleepless nights, long meetings, lines to wait in or difficult decisions to make. Like I would at the end of a 30-mile foot march, I can drop my rucksack and relax — for a very long time. Not even my old regimental sergeant major will be able to force me to get back up and keep marching. That’ll irritate him.

If buried at Arlington, I’d be not far from my father and mother, my wife Annie’s parents and brother, and the pre-Civil War home of fellow West Pointer Robert E. Lee. For different reasons, both Lee’s and my long careers in the Army didn’t end as we’d envisioned. And with life in general, I think that’s often the case. In the end, it is what it is — or, more correctly, what it was.

By custom and protocol, my remains will be brought to the grave site on a horse-driven caisson and followed by a riderless mount, symbolizing the fallen soldier’s trusted steed. I never rode a horse during my time in uniform, but families, as well as tourists, love the idea of it.

Immaculately uniformed and well-drilled soldiers of the Old Guard will move the remains, fold the flag and fire three volleys in salute, and then another will play a hauntingly beautiful version of “Taps.”

That’ll pretty much end the proceedings. Annie and other family will mingle briefly, then move to their parked cars. Any friends in town for the funeral may gather for drinks and funny stories afterward, but there will be flights to catch and lives to carry on. It will be over sooner than it started.

Despite its deeply human nature, character is curiously mathematical: character = convictions × discipline.

Soldiers have always pondered the value of their service. On a grand scale, defense of the nation, defeat of evil dictatorships and the freeing of enslaved people provide absolute clarity of the sacrifice. But on a more granular level, from the height of a soldier’s eyes, the worth of a hill captured or a terrorist killed is less clear when lofty objectives are never attained or simply abandoned. That’s the reality of the world, and soldiers know it. But knowing something doesn’t change the question: Does all this matter? Does any of it?

In the same way, it’s natural to question the true value of our character. If every road leads to the same grave site, why traverse difficult terrain carrying a heavy load? There are easier routes. Arlington cemetery’s ceremonies for veterans of both admirable and poor character are exactly the same, so the final chapter doesn’t vary. The burdensome discipline required to develop sound convictions and translate them into a life of character would seem to be energy wasted.

I’m reminded of the military axiom that the most difficult battles for soldiers to fight are those in which there is no hope of victory. But often, those battles must still be fought, and the real victory lies in the effort. The willingness to fight for what matters, regardless of outcome, is a concept that is difficult to explain, but essential to understand. Without it, we might ask, “If we’re all going to die, what’s the point of living?”

In the end, living is the point. Yet it is not when or where we live, but how we live. The score reflects a game’s outcome, but the manner of play defines its quality. The character we reflect summarizes our lives as no other metric can. Until the end, I will judge that my greatest challenge lies in closing the gap between the character I display and what I was capable of. We often hope players will “leave it all on the field,” and our pursuit of character should do nothing less.

Once the family and Old Guard soldiers depart, the grave will be filled in. Several weeks later, after cemetery officials ensure the inscription is correct, the headstone will be placed. More frequent at first, then only rarely, family members will come. Occasionally, tourists or visitors in search of another grave will recognize my name and perhaps pause briefly, maybe to relate a story of service we shared or something they heard.

Life continues. And if each of us lives by our convictions, I believe it will be better for us having lived.

From “On Character: Choices That Define A Life” by Gen. Stanley McChrystal, published by Portfolio, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright (c) 2025 by McChrystal Group LLC.

This story appears in the December 2025 issue of Deseret Magazine. Learn more about how to subscribe.