The schedule for Gov. Spencer Cox did not seem particularly demanding on the morning of Sept. 10. He had an event with some telecom execs in Mona, a small town of mostly pasture and lavender fields in Juab County, and then a quarterly birthday lunch back at the Capitol with his staff of about 20. He had no public events for the rest of the day.

He’d just returned from Mona and sat down in a conference room for lunch when his assistant came in and rushed to his side. “We need you and your chief of staff right now,” she whispered. The governor couldn’t recall her ever speaking to him with such urgency.

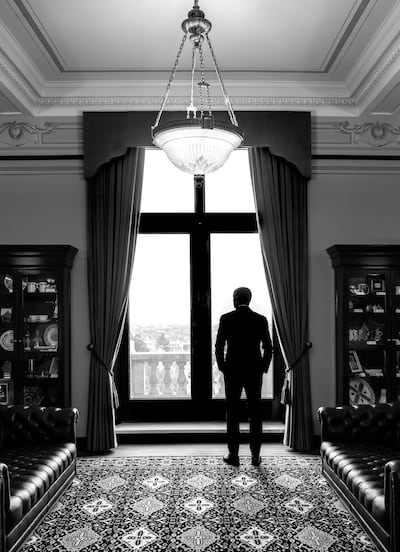

Cox shut the door behind him and stepped into his formal office — a high-ceiling chamber of marble and oak decorated with rodeo belt buckles and cowboy boots — to find a captain of the Utah Highway Patrol standing stiffly in his dress uniform: chocolate-brown shirt pressed to a crease, matching tan trousers, polished boots.

“Charlie Kirk has been shot,” he told the governor.

Cox’s mind spun, trying to make sense of what he had just heard. Charlie Kirk, he thought to himself. Charlie Kirk?

Then he remembered. Charlie Kirk was down at Utah Valley University in Orem. His staff had briefed him on the event days earlier. Kirk, head of Turning Point USA, was instrumental in mobilizing young voter turnout in the 2024 election for Donald Trump. He was famous for showing up at college campuses to argue with liberal students, which Cox admired, even though Kirk had once called for Cox to be expelled from the Republican Party.

As chairman of the National Governors Association, Cox had introduced an initiative called “Disagree Better” the year before. Cox didn’t agree with everything Kirk said, and, like much of Utah’s MAGA base, Kirk was no fan of the governor, but that was OK. That was the whole point of “Disagree Better.”

Kirk had picked Utah Valley as the first stop for “The American Comeback Tour,” a nationwide road trip across America’s college campuses. Cox knew there might be protests, but if there were, they would be small; Utah County was one of the reddest counties in America.

“They’ve taken him to the hospital,” the UHP captain said. “That’s all we know.”

“How do you know?” Cox said, his brain struggling to keep up. “What do you know?”

An assistant emerged from Cox’s working office and handed him a phone. A video played, posted to X. Charlie Kirk was seated under a white pavilion tent in front of a massive crowd on Utah Valley’s grassy quad. Cox had been there a million times. It was the largest of Utah’s public universities, with a student body of nearly 47,000. Kirk was wearing a white T-shirt with the word FREEDOM emblazoned across the front in black block lettering. Two security guards with earpieces stood a few feet away from him, one on each side, looking out at the crowd. Two others stood behind him, monitoring the perimeter. The crowd was full of college students wearing red Make America Great Again hats, or white ones with the number 47 on the side in gold lettering, a nod to Trump.

A student was at the mic asking Kirk something about transgender shooters. Kirk started to answer and suddenly there was a crack and then a gush of blood.

Cox felt a wave of nausea and a sickening pit in his stomach, heavy as lead. His mind flashed back to a video he’d recently seen of Kirk with his daughter running toward him.

Cox said a silent prayer. “Please, God,” he pleaded. “Please keep him alive. That’s all. We just have to keep him alive.”

Thirty seconds later, Cox’s cellphone rang. It was the White House. The secretary of state, Marco Rubio, was in the Situation Room and had just heard about the shooting. The president wanted an update.

He told Rubio what he knew. Cox had the Utah Commissioner of Public Safety on the other line, who was getting briefed from a Highway Patrol officer at Timpanogos, the hospital Kirk had been rushed to after the shooting. “It’s not great,” Cox told Rubio.

Fifteen minutes later, Cox called Rubio back. “I’m so sorry,” he told the secretary of state. “We just got condition fatal.”

Rubio let out a deep sigh. “Thank you,” he said. “I’ll tell the president.”

When the president called an hour or so later, Cox updated him on what they knew. Surveillance video from campus police had picked up footage of a suspect in black on the roof of a building near the quad running east. The shot had come from that area, Cox reported.

Later, when Trump would speak about the killing, his words would be laced with anger, but on the phone with Cox there was no anger, just shock, and a deep sadness. Kirk had been a close personal friend, the president said. He’d helped him get elected. “You know who loved Charlie?” the president asked. “The young people. The young people really loved Charlie.”

“I’m so sorry, Mr. President,” Cox said. His mind immediately started to spin forward, to what this meant for Utah, but more than that, what it meant for the nation. Cox had been warning for some time that America’s growing polarization was becoming deeply dangerous, but it didn’t seem anyone was listening. Then the president had nearly been assassinated. Gov. Josh Shapiro’s home had been firebombed. Two Minnesota lawmakers and their spouses had been shot — one of the couples died in the attack — in their own homes. And now this.

The moment he feared had arrived.

A private reckoning

The Utah Governor’s Mansion is about five blocks east of the Lion House, the official residence of the first territorial governor, Brigham Young. A soaring French-style chateau of granite and limestone, it was built by a 20th century Park City mining magnate, who insisted on Italian and African marble for the floors. The mansion has been renovated several times, most recently in 2021 for security upgrades, and anyone who visits today must be buzzed in and escorted through several security checkpoints.

It was near midnight on Sept. 10, roughly 11 hours after the shooting, when the governor finally arrived home. The public rooms on the main floor, with their hand-carved woodwork and formal parlors, were dark by then, and the house was quiet and still; the staff of the first lady, Abby Cox, had gone home for the day. She was upstairs in the private residence, already in bed.

They had both been “sober” from cable news for about 12 years, Cox liked to joke, and Abby had deleted all her social media accounts from her phone during her husband’s first gubernatorial run, about five years before, meaning neither followed the news at home. As much as possible, whatever hours they had together were a sanctuary from the outside world.

At least two nights a week, sometimes three, there were dinners and events and formal parties to attend around town, and sometimes downstairs. On the rare nights that they had to themselves, they watched sports. Cox had been a fanatic of the Utah Jazz since he was a kid, but he loved watching college football too — the Utes and the Cougars and the Aggies — and he was trying to watch as many games as he could of Utah’s newest franchise, the Mammoth of the NHL.

Anyone who knew the governor and the first lady noticed they were unusually close. “More so than any other couple I’ve ever seen, they are a package deal,” one of their friends, Spencer Hall, told me. It’s hard to see “where one ends and the other starts.”

Kirk had once called for Cox to be expelled from the Republican Party.

They had both grown up near Fairview, a town of 1,300 about an hour and a half south of Salt Lake City, and when Cox was asked to become lieutenant governor, in 2013, he did so on the condition he could stay there, meaning he commuted back and forth to the state Capitol twice a day, 100 miles each way. He and Abby wanted their four children to have the same upbringing they had, getting up at 5 a.m. to move irrigation pipe, learning how to drive tractors at age 10, and how to mark the seasons by the sweet smell of cut hay.

After law school in Virginia, they had returned to Fairview, where Cox served on the city council, and then, like his father, became the mayor. He was just 33. He was also the bishop of the Fairview Latter-day Saint congregation, which meant sometimes he’d order the power turned off for an unpaid bill as mayor and then show up as bishop to help turn it back on.

To see pictures of Cox from that era is to see a man infused with hope and idealism. His hair formed a bushy halo around his balding head. He wore baggy, out-of-style jeans with dress shoes, and played in a Killers cover band.

When he ran for governor in 2019, few thought he could beat Jon Huntsman Jr., the former two-term governor, presidential candidate, and scion of one of the state’s most prominent and wealthy families. But Cox ran a relentlessly cheery campaign — presenting himself as somewhere in the middle between Huntsman’s watered-down conservatism and the hard edge of the far-right candidate. He painted an RV green and yellow, in the gradient colors of the Jazz uniform, and visited 248 cities in the state. He presented himself as a unifier — someone who could hold court with the tech bros in Utah County as well as the farmers and ranchers from places like Fairview. He dressed the part too, usually in the plain, slightly rumpled uniform of a man more accustomed to county-fair stages than “Meet the Press.” Here was a local boy who had gone on a Latter-day Saint mission to Mexico, got a 4.0 GPA at Utah State, and then turned down Harvard Law for Washington and Lee, a school known for polishing the Southern patrician elite into statesmen attorneys who modeled civility. He didn’t say “Disagree Better” just yet, but it was on his mind. “We’re better when we work together,” he said, in what amounted to a campaign slogan.

Cox didn’t see Trump as his enemy, but he had concluded that being seen as his enemy had not accomplished anything.

Now lying in bed, Abby watched her husband pace across the creaky floors of the century-old mansion. She couldn’t tell exactly what he was saying, but she caught snatches of his phone conversations with the FBI director, the Utah Department of Public Safety and police officers down in Utah County, maybe the White House.

She could tell he was trying to protect her, careful with what he chose to share. “I think we have a really good lead,” he told her sometime after midnight. But it fell apart quickly, and they were back to square one. How on earth had the shooter got away in such a public place, packed with people, she wondered.

As she drifted off to sleep, her husband was still on the phone.

When she woke up the next morning, he was already gone.

The inner circle

During Cox’s time as lieutenant governor, a small, tight-knit friend group had coalesced around him. Some, like Jon Cox, a distant relative, had once had informal roles in his administration (they jokingly referred to themselves as a “kitchen” cabinet). By 2023, when Cox was running for reelection, none were political advisers anymore — they were just close friends with a group text thread they were all on every day. “It runs the gamut,” a friend from the group named Ryan Beck told me.

The group had become something of a sounding board and safe place for Cox, and each year, they camped together, a guys-only outing somewhere in Utah’s remote wilderness. (Beck told me Cox was always the first up to start the fire.)

The day after Charlie Kirk’s killing, Cox slipped out of his office to meet the group for a quick lunch. He told them he only had an hour, but he was still processing the magnitude of the killing and what it would mean for Utah, and the nation. He was humming with adrenaline and said he hadn’t slept, something that had become common since taking office.

The manhunt for the killer was his main focus, and most of his energy was taken up by coordinating the work of Utah’s Department of Public Safety with local police agencies and the FBI. “He was just starting to appreciate just how global this moment was,” Beck told me. “He recognized that this could be a massive accelerant to the forces in America he’d spent his career trying to marginalize.”

The calls for retribution had already begun. “The Left is the party of murder,” Elon Musk wrote on X.

“Charlie Kirk is a casualty of war,” Steve Bannon, a longtime Trump adviser, said.

Unless someone could turn the temperature down, Cox worried this sort of rhetoric could escalate. The irony is that Kirk had never called for violence, and instead had modeled a form of civil dialogue. “Charlie, at his best, wanted what Spencer wanted,” Beck said.

During his first term, Cox had concluded that political polarization had become one of America’s biggest problems, that if we couldn’t get past that, we could never get to the very unglamorous work of governing. He had begun studying the years leading up to the assassinations of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy and became particularly intrigued by the work of Rachel Kleinfeld, a political scientist at the Carnegie Endowment, who had spent her career studying how countries slide from ordinary partisanship into what she called “pernicious polarization,” which can upend democracies if left unchecked.

When citizens began to justify intimidation, threats and the dehumanization of rivals; when parties adopted a win-at-all-costs mentality; when leaders decided that fear was more useful than persuasion — political violence followed. In Kleinfeld’s telling, America was not immune. It was already further down the path than most people wanted to admit.

Cox had seen the warning signs firsthand. His lieutenant governor, Deidre Henderson, had received so many death threats over false allegations of election fraud she now rethought trips to the grocery store alone. At least two people were in prison for credible death threats to Cox’s predecessor, former Gov. Gary Herbert. One of Cox’s longtime aides, Mike Mower, had served in every governor’s administration since 2005. He pointed out that when he started, there wasn’t a fence around the Governor’s Mansion. Then they built a 3-foot fence, Mower told me. “Now it’s 6 feet tall.”

In 2023, Cox was elected chair of the National Governors Association. Each governor picks an initiative for the year, and Cox considered pressing issues that affected both his state and the broader nation, like the rising cost of health care, or the need for additional energy and minerals for the coming AI boom. As pressing as those issues were, he concluded nothing had become a bigger problem in American politics than polarization. He decided his focus for the year would be “Disagree Better,” an idea he had gotten from Arthur Brooks, the Harvard professor and New York Times bestselling author.

For his first gubernatorial election bid, in 2020, Cox approached his Democratic opponent, Chris Peterson, and asked him if he wanted to make a campaign ad together. Peterson was shocked, but agreed to the ad, which featured Cox in a red tie and Peterson in a blue one saying that while they disagreed with each other on almost every issue, they could still be friends. The ad was surprisingly effective: Researchers at Stanford found that viewers came away noticeably less hostile toward the other side. Cox took the idea national, persuading pairs of politicians from both parties to film their own versions.

While the idea gained traction nationally, it was not well received in Cox’s own state, especially among his own party. At the GOP convention in April 2024, he was lustily booed, and one of his opponents — a cowboy-hat-wearing sheep farmer and former state party chair — had dedicated his entire stump speech to the idea of not disagreeing better.

“Don’t vote for me if you want to disagree better,” he said. “Vote for me if you know we better disagree.”

His leading primary opponent, Phil Lyman, called “Disagree Better” a “leftist, Marxist tactic to get people to drop their opinions.” Cox pushed back that this wasn’t the idea at all. You could have your opinions; you should have your opinions and stand up for them. You just didn’t have to hate those you disagreed with.

As Cox toured the state during the primary, he was dismayed by how much things had changed in Utah in just four years. Where his first campaign had been joyous and energizing, a confirmation of all the things he loved about Utah, he was now met with looks of skepticism and distrust. Lyman was using X to spread disinformation — that the Chinese government was funding the Cox campaign, that the governor was interfering with the Wi-Fi to censor the news and bussing in immigrants in the country illegally from Colorado to vote for him. “People we know and love were literally believing the stuff being said,” Abby told me. He could defend his record as conservative, but this didn’t seem to matter. He had declined to vote for Trump in 2016, and again in 2020. He had turned his back on the party, and so they would turn their backs on him.

Cox won the primary, but the distortions from Lyman and his allies had an effect. Lyman mounted a write-in campaign that had the feral energy of an insurrection (handwritten signs on street corners, banners taped to highway overpasses) and had carried 8% of the vote. (I texted Lyman requesting an interview for this story for weeks until he stopped responding to my texts or calls.)

His staff told him the same thing his friends had told him: Someone needed to turn the temperature down, and they worried that if Cox didn’t do it, nobody would.

The experience had left Cox bruised. He had long liked walking through cemeteries in quiet moments, and on Sundays, he often found himself with Abby at the Salt Lake City cemetery, among the tall granite headstones and monuments to Utah pioneers. It gave him perspective on the long arc of history. This moment felt fraught and unprecedented, but Americans had been through worse. One day, he would be forgotten, his body long since decomposed beneath a chunk of rock. The principles he stood for, though? They would endure, for better or worse.

He had come to see “Disagree Better” as more than a political slogan. Among his texting friend group, they turned often to a sermon the Rev. King had delivered in 1957 in Montgomery, Alabama. It centered on the fifth chapter of the Gospel of Matthew, and the command to love your enemies. Love implied a long-term relationship, the Rev. King pointed out. It implied commitment. And only in love could you persuade. Only love had the power to transform.

In July of that year, Trump had survived an assassination attempt by mere inches in Butler, Pennsylvania. The next day, Cox was sitting in church with his family, when the thought came to him that he should write Trump a letter.

Cox had intended the letter to be private, but it leaked, and when he had been asked about it at a press conference, he said he planned to vote for Trump. Some of his closest friends were aghast and asked for private audiences to plead with him to change his mind. (One told me that when Cox defended the decision by saying it had come after prayer, the friend shot back: “Well, maybe you should pray again.”)

Cox tried to explain his decision in pragmatic terms, but the reality is, he couldn’t quite explain why he had written the letter, or why he had decided to vote for the president. He had felt that there would come a time when he needed to have influence within the party, and upon the president himself. And now, that moment had arrived.

How had we gotten to the point where our entire character was defined by who we vote for?

After lunch on Sept. 11, Cox returned to his office at the Capitol, where he met with his staff. By that point, two suspects had been detained and released. Investigators, both in Utah and at FBI headquarters in Quantico, Virginia, were reviewing surveillance footage of a suspect in a stairwell on the Utah Valley campus.

Cox knew it was a matter of time before they caught Kirk’s killer. What worried him was what might happen until then, or in the aftermath, depending on the suspect’s motives. Already conspiracy theories were blossoming online, about antifa, or that the shooter was motivated by “transgender ideology.” It was the exact sort of scenario Cox had been studying for the past two years in trying to understand what led to the assassinations of the Rev. King and RFK. It was the sort of tinderbox Kleinfeld had warned against.

His staff told him the same thing his friends at lunch had told him. Someone needed to turn the temperature down, and they worried that if he didn’t do it, nobody would.

The moment to lead

At a little after 8 a.m. on Sept. 12, roughly 44 hours since the shooting, Cox stood before the press. Rumors had been circulating since early that morning that a suspect was in custody. In the 12 years Cox had been part of the governor’s office, he’d never seen so many news cameras in one place.

“Good morning, ladies and gentlemen,” he began. “We got him.”

He went on to explain the events that led up to the capture of their suspect, a 22-year-old from a small town in southern Utah named Tyler Robinson. The tip had come from a retired police detective who knew the Robinson family. Robinson’s father had turned him in.

He briefly reviewed the evidence Robinson allegedly left behind, and clues that may have suggested his motives, including a bolt-action rifle wrapped in a towel and transcriptions on bullet casings.

He described the killing as a “political assassination” and warned that the country was at a moment of serious fracture. As he had been doing for some time, he called out the role of social media in escalating division, even feeding off it.

He turned his attention to the rising generation. “You are inheriting a country where politics feels like rage. It feels like rage is the only option.” But that wasn’t true, he insisted. “Your generation has an opportunity to build a culture that is very different than what we are suffering through right now.”

We could return violence with violence, he said, or we could find a better way.

Throughout the day, Cox’s phone lit up with calls and text messages, thanking him for his words. They came from friends in Fairview, from former Latter-day Saint mission companions, from the governors of Hawaii and Wyoming, from Jeb Bush and Asa Hutchinson.

And then they started coming in from numbers Cox didn’t recognize. He wouldn’t tell me who they came from exactly, but he did say they were heads of state. That night, Cox spent eight hours responding to emails and text messages.

“A lot of blame and finger-pointing had been happening at that point,” Lt. Gov. Deidre Henderson told me. “The governor recognized that he had an opportunity to do things differently and to give a message that wasn’t being given at that time and one that was desperately needed.”

Hundreds of media requests came in, but Cox didn’t want to do any more media, especially national media. He was tired of being used as a prop that played foil to Trump. He had slept for maybe 90 minutes over the past two days, and wanted to spend time with his family, especially his children, who were getting death threats.

But he did do media. He went on Ezra Klein’s New York Times podcast, he went on “60 Minutes,” and he did all the Sunday shows, from “Meet the Press” on NBC to “This Week” on ABC to “Face the Nation” on CBS. He did so partly because he believed in his message of unity, of the principles behind “Disagree Better,” and that the nation needed it. And he did so because the president had asked him if he would.

After the shock

In November, roughly two months after Charlie Kirk’s death, I met Cox at his office in the Capitol.

Friends told me the year prior to Kirk’s killing had been perhaps the most difficult in Cox’s time in public service, which has spanned two decades, even though he is only 50. The eager affability and earnestness that had long defined him now has a slightly guarded edge. His strong jawline seems more pronounced, and his eyes carry a certain wariness.

He had always thought of himself as someone who could bridge differences, and Utah as relatively immune from the darker currents running through national politics. Prior to becoming governor, he had seen the state reach compromises on immigration and LGBTQ rights that were unusual for a red state, but when he had tried to do something similar on trans kids playing high school sports in 2022, it had blown up in his face. Tucker Carlson had dedicated an entire segment to him, calling Cox “creepy” and woke, and wondering how a “low IQ weekend MSNBC anchor” had become governor of a red state. Ironically, it was over this same issue that Kirk had said Cox should be expelled from the GOP. At a campaign event in 2024 for Trent Staggs, a pro-Trump candidate running for Mitt Romney’s open U.S. Senate seat, Kirk asked the audience, “Can you believe your governor? What is wrong with this guy?”

When he decided to vote for Trump later that summer, many of his friends to the left of him were just as vicious. Stuart Reid, a Never Trump Republican and former state senator, excoriated him in an open letter published in The Salt Lake Tribune: “You have lost your credibility and relinquished your honor.” Democratic allies and moderates in Utah he had considered friends turned on him.

This baffled Cox. How had we gotten to the point where our entire character was defined by who we vote for? How had we gotten to the point where we stop talking to family and friends if they don’t share our politics?

Cox had previously explained his decision to vote for Trump in somewhat tortured political terms, but I wondered if there was something deeper, something beyond political calculation. I wondered if the decision had been informed in part by his study of the sermons of the Rev. King and the biblical idea of forgiving our enemies.

When I asked his wife Abby about this, she stressed that while her husband had never seen Trump as his enemy, he had concluded that being seen as his enemy had not accomplished anything. In fact, it had perhaps been counterproductive in getting elements of his own party on board with his message.

Cox pointed out that in his own state, and maybe around the nation, he’d made more inroads with Democrats with the “Disagree Better” idea than within his own party.

“I haven’t been great at that,” he admitted. “In the past, I’ve alienated some people within my own party who didn’t deserve to be alienated, lumping people together in ways that weren’t helpful.”

He was referring to the previous spring, when he had been loudly booed at the state GOP convention. He had responded by pointing out that his record was unassailably conservative: the largest tax-cut in Utah history, a transgender bathroom bill, the shuttering of abortion clinics, making it legal to carry a gun without a permit.

So why did they hate him? It didn’t make any sense. “Maybe you just hate that I don’t hate enough,” he said.

Cox’s friends told me they loved the line. Finally, after years of taking it on the chin from the likes of Tucker Carlson, he was firing back. But he told me he immediately regretted it. Republican committees from around the state, including Iron, Davis and Salt Lake counties, all condemned the speech and demanded Cox apologize.

“If I could go back and do that differently, I would,” he said. “It’s taken me a long time to heal, to mend some of those relationships. And some of them, I may never be able to mend.”

Since the shooting, much had been made of a call President Trump had with Cox after the press conference announcing Robinson’s arrest. “You know, the person who shot Charlie would have loved to shoot (us),” Cox says the president told him.

National media had cast the call as a warning, but Cox said that wasn’t how he saw it. He told me he and the president spoke for an hour, on everything from why the National Guard was in Chicago to how he’d reduced the flow of immigrants entering the country illegally across the southern border. Toward the end of the call, the president thanked Cox for his message and said he had agreed with it. He would later ask through his staff for Cox to do the Sunday shows.

“Everybody wants to pit me against the president,” Cox said, “but to have him tell me twice on that phone call that he appreciated what I said, like that means something. And I don’t get that opportunity if he and I are just fighting.”

I think the vast majority of the people of the United States are hungry for some moral clarity.

“I’m not trying to pick fights,” he went on. “I’m trying to win converts. And that’s a very different philosophy, and a very different conversation and a very different calculation.”

Trump hadn’t exactly been pushing “Disagree Better” since Kirk’s murder. Instead, he had called for “beating the hell” out of “radical left lunatics,” and promised investigations into “leftist” organizations he said contributed to political violence. Famously, when Kirk’s widow Erika said she forgave her husband’s killer during a memorial service, Trump spoke next and jokingly said he didn’t forgive or forget. If Cox had voted for the president to have more influence within the party, and upon the president himself, I asked him if he thought it was working.

“I mean, I guess as a neutral observer people would say, probably not,” Cox said with a laugh. “I don’t know that he’s changed, but it allows me to have those conversations, to have some influence.”

Prior to Kirk’s killing, Cox had begun to wonder if America could pull itself back from an era riven by discord. But the way the country responded after Kirk’s assassination had given him a glimmer of hope. In Utah, there had been no riots. In fact, there hadn’t been rioting anywhere. And while there had been some calls for reprisal on the right, none had materialized.

Much of the national media had credited Cox for this, pointing out that it was him, and not the president, who had met the moment with a message that turned down the temperature.

“In any other state, local politicians might have either become targets for President Donald Trump or leapt to inflame the situation,” David A. Graham wrote in The Atlantic. “But the Beehive State’s governor is perhaps the most consistent voice of calm and conciliation in the GOP.”

Predictably, in the wake of Kirk’s killing, there have been questions about Cox’s future. He ends his second term as governor as Trump ends his second term as president, in 2028. Perhaps the mood of the country will have shifted by then, and the sort of quiet, dignified leadership Cox has long tried to model will make him a viable presidential candidate.

Cox’s friends have encouraged him to at least think about it.

“I think the vast majority of the people of the United States are hungry for some moral clarity,” Lt. Gov. Henderson told me. “They’re hungry for leadership. They’re hungry for an example of doing things differently and rising above the rancor.”

Cox said he feels energized that his message of “Disagree Better” is finally seeming to resonate, but that he has no interest in higher office. Things may change, but for now, he says that when he finishes his term, he will be done with politics.

Friends say he might go back to Fairview, if they’ll have him. And if not Fairview, somewhere else quiet, away from all the noise.

This story appears in the January/February 2026 issue of Deseret Magazine. Learn more about how to subscribe.